Sri Lanka received a bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in March amid soaring inflation, debt and a sovereign default.

In exchange for US$3 billion (£2.4 billion), the government committed to spending cuts and tax and financial sector reforms. These have prevented Sri Lankan wages from recovering after they fell by almost half in real terms during the preceding financial crisis, leading to protests in the streets of Colombo.

Sri Lankans’ experience of these measures has been far from uniform. Emerging evidence indicates that the government — led by Ranil Wickremesinghe, part of the Buddhist Sinhalese majority — has concentrated the burdens primarily on ethnic minorities, who are the poorest in Sri Lanka and typically support the opposition.

The government has sought to protect the elite, which is primarily Buddhist Sinhalese, by avoiding imposing wealth taxes and only making small increases in corporation tax. It has placed the costs of austerity on low-income people by doubling the value-added tax rate to 15%.

It has also doubled the tax that people pay on pension-fund returns. Again, this hits poor ethnic minorities hardest because they frequently earn too little to pay income tax.

Unfortunately, this experience is part of a worldwide pattern. Our new book, IMF Lending: Partisanship, Punishment and Protest, shows how governments lump the burden of adjustment on opposition supporters while shielding their own backers – in other words, using IMF programmes for political gain.

IMF programmes and past research

Scholars have long noted that IMF restructuring programmes create winners and losers, but always in relation to different sectors of the economy. For example, the fact that programmes attempt to strengthen exports has been shown to favour farmers and business owners over urban middle-class state employees like civil servants.

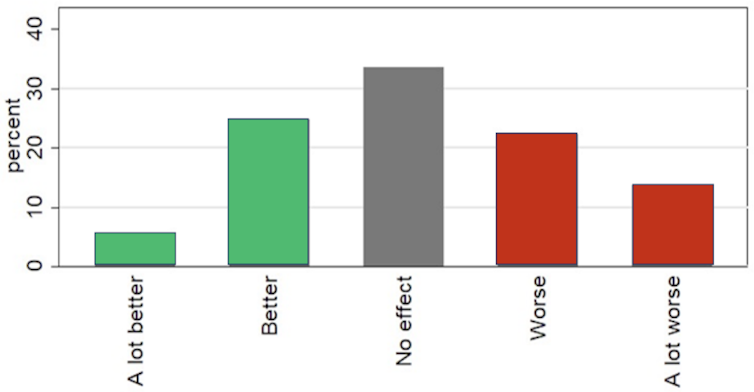

The problem with purely comparing sectors is highlighted when you look at citizens’ experiences. One segment of the survey data we used in our research, covering nine countries in Africa, showed that three out of ten civil servants actually thought IMF reforms made their lives better, while a similar proportion observed no difference.

Admittedly this data is from 1999-2001, since none of the more recent surveys that we used asked this question, but it raises an important point: if IMF reforms are entirely bad for the civil service, why are so many civil servants upbeat about the effects? Politics is likely to be the missing piece of the puzzle.

Citizens’ views of IMF programmes in their countries

An extensive academic literature already shows that governments often use their discretion to play politics over development loans. For example, a recent study found that projects funded by Chinese money are more likely to be undertaken in the birth region of a political leader.

With IMF programmes, it’s commonly assumed that they narrow borrowing governments’ policy options, but that is an oversimplification. Borrowers certainly have less overall freedom over economic policy, but they maintain broad discretion in how they implement loan conditions. Our study is the first to quantify how they use this discretion and examine the consequences for protests within the countries in question.

Our study

We collected individual survey data from over 100 countries from four widely used sources: Afrobarometer, Asian Barometer, Latinobarómetro and the World Values Surveys. It covers a 40-year timespan up to the late 2010s, with periods varying from region to region.

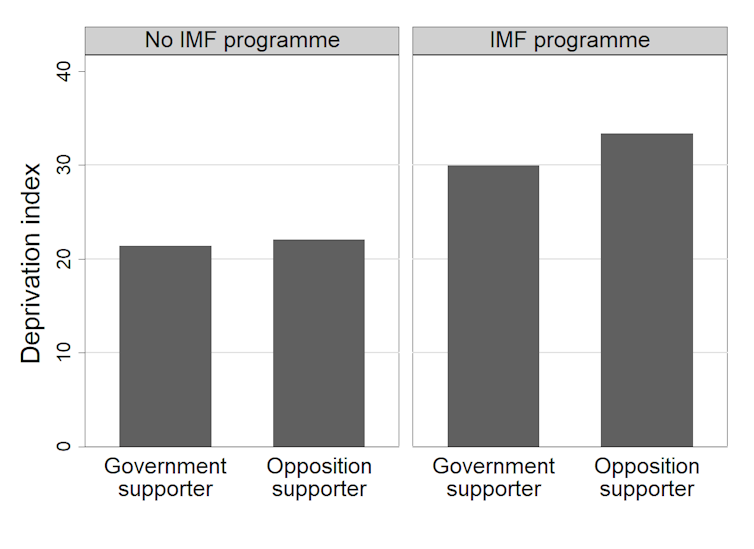

We first examined whether opposition supporters had different experiences of reforms than government supporters. Sure enough, these were indeed more negative.

We worried this might be because these people are more critical of their governments in general. So we compared countries which had just experienced a restructuring programme with others which had not, and found that sentiment among opposition supporters was much more negative in borrower countries.

The following graph provides an explanation, showing that opposition supporters in countries on IMF programmes suffer relatively more deprivation than government supporters compared to countries not in programmes.

Partisan deprivation in IMF v non-IMF countries

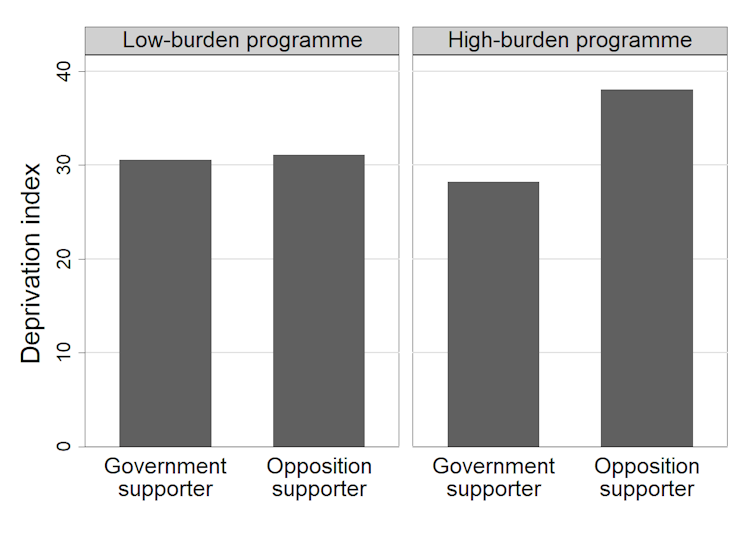

This “partisan gap” was also wider in countries who went through a more burdensome recent IMF adjustment, which points to the same conclusion.

Partisan deprivation by severity of IMF restructuring

The effect on protest

We expected that this highly unequal treatment would increase the chances of protest – especially when stoked by opposition politicians. This too was robustly supported across the surveys.

In Africa, people who reported being worse off due to the structural adjustment programme were more likely to protest. Opposition supporters as a whole were also more likely to protest, especially if the country had just experienced a more severe IMF programme.

Again, this data was from 1999-2001. Nonetheless, the other surveys also showed that protest was more likely among opposition supporters, especially during times of high pressure for adjustment.

What can be done

Scholars normally blame the increase in inequality caused by IMF programmes on the loan conditions, but the effects are clearly amplified by governments’ policy choices. How could this situation be improved? The IMF could require borrower countries to impose loan conditions in a non-partisan way, but would probably argue that its mandate prohibits considering domestic politics. Policing this would also be very difficult and time-consuming.

An alternative would be for the IMF to tame its demands on borrower countries. This would reduce the burdens that could be inflicted on opposition supporters. Economists might warn that this could encourage countries to be more financially irresponsible. Equally, however, it ought to make it more likely that adjustment programmes will be completed, thereby making the borrowing country more economically resilient for the future. It would also avoid any adverse reaction from the financial markets against a country breaking conditions.

Another potential avenue is to let opposition parties and civil society organisations participate in bailout negotiations. This would ensure everyone “owns” the bailout, and might even make it harder for incumbent governments to exploit policy conditions for political gain.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.