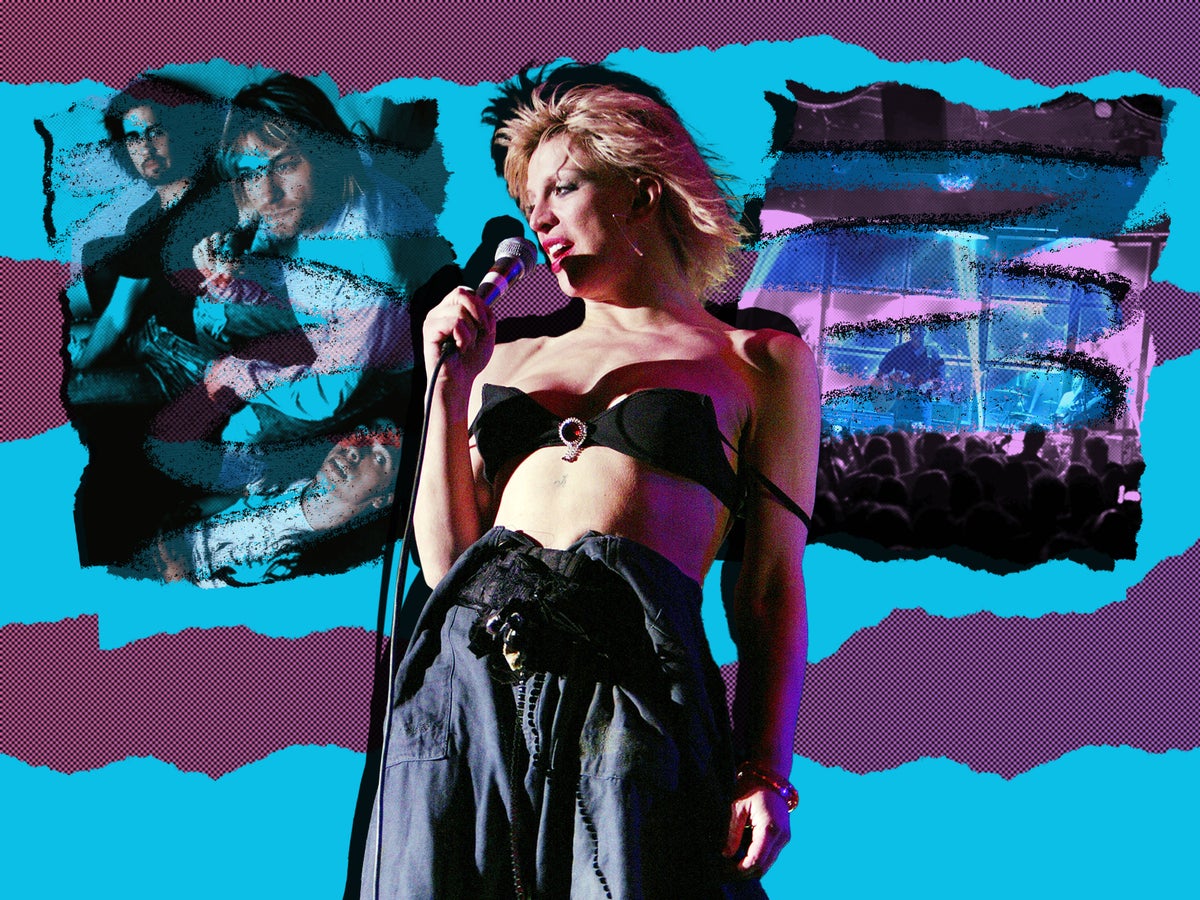

Courtney Love’s voice vaulted rasping and raw from the speakers and, for an instant, Tallulah Sim-Savage forgot she was breathing. “My mind was blown that a woman was singing that sort of music,” says Sim-Savage, frontwoman of up-and-coming indie band HotWax.

The singer and guitarist was just 11 when her mother introduced her to Love’s group, Hole, and their angst-packed 1994 album, Live Through This. Released in the shadow of the suicide of Love’s husband, Kurt Cobain, the record was a pile-driving mix of trauma and rage. That blend of quiet and loud had a life-changing effect on Sim-Savage, growing up in Hastings, East Sussex, and, seven years later, as she and her bandmates prepare to release their effervescent, punchy debut EP, A Thousand Times, she remains devoted to the 1990s indie aesthetic.

A Thousand Times is a zinging calling card from a trio just out of school – their GCSEs were interrupted by Covid – and going places in a hurry. It also marks HotWax as part of a wider movement of Gen Zers who have fallen hard for that classic early 1990s indie template of detonating hooks and whispered verses – a formula pioneered, from the late 1980s onwards, by underdogs such as Pixies and then turned into a commercial steamroller in the following decade by Nirvana.

It is an ever-expanding club. Alongside HotWax, there are American artists such as Soccer Mommy, Beach Bunny and Snail Mail – and, with her new LP, Blondshell’s Sabrina Teitelbaum, who also name-checks Courtney Love as an influence.

Meanwhile, on this side of the Atlantic, the Sussex-based HotWax are joined by the whisper-to-a-scream pop rock of west Londoner beabadoobee and, more recently, Arlo Parks, whose forthcoming second LP, My Soft Machine, is smeared in grungy student disco guitar. There is also Bleach Lab, from south London, with a loud-yet-vulnerable formula that incorporates a love for such signature Gen X sounds as the woozy romanticism of Mazzy Star and the de-tuned guitar assault of My Bloody Valentine.

“It’s the nostalgia thing,” says Bleach Lab vocalist Jenna Kyle. “People that are in their twenties – the 1990s was when we were kids. Things might not have been the best for adults. But that’s not what we remembered.”

As Kyle suggests, there is an element of false memory at play here. Back in the 1990s, nobody would have expected indie underdogs blending jangling guitar and cathartic choruses to become the unofficial soundtrack of the decade.

Boy bands, the Spice Girls and Britpop were among the dominant cultural influences of the era. Say “1990s music” today, however, and what comes to mind, more often than not, is that quiet/loud dynamic. The obvious paradox is that, except for Nirvana, these groups weren’t all that popular the first time around.

It helps that guitar rock tends to age better than other genres. Pop and electronica are often tied to the technology of their era. A pop song from 30 years ago will date far more quickly than a lo-fi indie anthem from the same period. “Pixies, Dinosaur Jr., Nirvana, etc don’t sound out of step or outdated, they just sound cool,” says Brett Vargo of the alternative music podcast Only Three Lads. “They sound like youth. They sound like freedom. They sound like the jumbled web of emotions that we’ve all tried to unravel at some point.”

The embrace of 1990s indie by musicians often barely in their twenties – all of HotWax were born in 2004 – is, some commentators believe, part of a wider rediscovery of the decade by adults too young to remember it first-hand. It is a trend that can also be seen in the popularity of Friends and the vogue for remaking classic 1990s video games such as the Resident Evil series. And even in the career revival of Keanu Reeves who, until John Wick, was joined at the hip with his two 1990s franchises, Bill and Ted and The Matrix.

“There has been, since the mid-2010s, a return of the 1990s in contemporary culture,” says Dr Neil Ewen, senior lecturer in communications at the University of Exeter. “You can see that especially on Netflix and other streamers [with series such as That ’90s Show and Yellowjackets, which have their roots in the 1990s with soundtracks to match] and in music culture as well. In the 2010s, you had grunge bands who had dissolved getting back together. Before [their lead singer] Chris Cornell died, Soundgarden got back together. I remember seeing Babes in Toyland, who had reformed.”

Bleach Lab’s Jenna Kyle only has her tongue slightly in cheek when she says that she “remembers” the 1990s as the “good old days”. In the popular imagination of many Gen Zers, the final decade of the 20th century was a time of innocence and possibility. Of course, the reality was more complicated; this was the decade when Monica Lewinsky was shamed for her relationship with Bill Clinton while he ambled into the sunset, and of war crimes in the Balkans, the Columbine massacre and the Rwandan genocide.

But we don’t remember the 1990s like that: we think of Kurt Cobain and his tatty cardigan conquering the mainstream and of the Friends cast shooting the breeze at Central Perk, with no fear of Twitter pile-ons or zero-hour contracts. Among musicians, there is the further sense of the decade as the last time music could move mountains, whether that be grunge aiming its ire at corporate rock or Riot Grrrl outfits such as Bikini Kill and Huggy Bear taking on the patriarchy.

“Grunge was probably the last political movement in music: it was explicitly anti-commercial,” says Neil Ewen. “You had Kurt Cobain talking about stuff like masculinity and rape culture.”

Gen Z bands paying tribute to the 1990s often do so by accident, it is worth pointing out. “We were always compared to The Sundays – a band I hadn’t actually heard. I’ve gone back and listened to them,” says Bleach Lab drummer Kieran Weston. “It’s interesting when you’re compared to someone you never knew. And then you go back and you’re like, ‘Wow – we do sound like that.’”

Not all artists are at ease with the association. After beabadoobee’s Bea Laus put out her first album, Fake It Flowers in 2020, she was nonplussed to be compared to the sparkling Nineties indie rock of The Breeders and the gilded grunge of Smashing Pumpkins – and to be heralded, in certain corners of the internet, as a purveyor of nostalgia for greying indie dads.

She had invited this on herself to a degree by name-checking in an early single Stephen Malkmus of iconic Nineties “slacker” group Pavement. Nonetheless, Laus saw herself as writing songs for people in their early twenties like her – and so leant away from the indie aesthetic on her poppier second LP, Beatopia, as she told me subsequently.

“It was a bit annoying,” she said of the 1990s tag. “But also flattering. People were saying that my music felt nostalgic and made them think back to that time: blah, blah blah. The thing is, I don’t do things consciously. Everyone gets inspired by everything. Nothing is completely original nowadays. Yes, maybe I’m going to have hints of certain records from certain decades. That’s because I try to find inspiration everywhere.”

HotWax are ambivalent, too. Their musical tastes were framed, in part, by their parents, who happened to come of age in the 1990s. But while they acknowledge these influences, they don’t want to be defined by them. They’ve only recorded their first EP. Their journey has just begun. They will continue to grow as artists – and who knows where and how the 1990s will fit into that equation.

“When you start playing guitar, everyone gets taught [Nirvana’s 1991 anthem of disaffection] Smells like Teen Spirit,” says bassist Lola Sam.

“I don’t think it’s ever an intentional thing,” agrees Bleach Lab’s Kieran Weston. “We never say, ‘We want this to sound 1990s.’ A lot of the music we all listen to – it is those 1990s bands. By writing music we like and enjoy, it indirectly sounds like it. It’s not intentional. Naturally, because of our influences, it just kind of happens.”

A Thousand Times by HotWax is released on 19 May

Bleach Lab release their debut album, Lost in a Rush of Emptiness, in September