Conspiracy theories have always been a part of society, offering explanations – sometimes simple, often elaborate – for complex events.

Some have uncovered genuine conspiracies, such as the Watergate scandal. Most lack substance but are nevertheless widely believed. For instance, the idea that the moon landing was staged has persisted for decades despite substantial evidence to the contrary.

What drives people to adopt these beliefs? Researchers have been investigating the underlying mechanisms that foster conspiracy beliefs and our new study adds another piece to this puzzle.

Using data from more than 55,000 people who participated in the longitudinal New Zealand attitudes and values study, we found certain core psychological needs attract people to conspiracy theories. When these needs go unmet over long periods of time, people are more likely to turn to conspiracy beliefs, possibly as a way to fulfil these needs.

Why conspiracy beliefs hold such appeal

Past research suggests three core motivations that can underlie conspiracy belief.

First, people have an epistemic motive (relating to knowledge) to restore understanding and clarity about the world. Second, people’s existential motive captures the need for control and security, particularly in unpredictable situations. Finally, people have a social motive to belong and maintain a sense of shared identity.

Together, these motives help explain why some people turn to conspiracy theories to make sense of situations in which they feel powerless or disconnected. Events such as the COVID pandemic provide fertile ground for these beliefs to take hold.

However, there are clear negative consequences of conspiracy beliefs. They often foster distrust in authorities, encourage the spread of misinformation and, in some cases, make people take actions that harm society as a whole.

By understanding the psychological needs behind these beliefs, we can start to address them at their root.

Core needs linked to conspiracy beliefs

Our research focused on four key psychological needs closely linked to the three motives above: control, belonging, self-esteem and meaning in life.

We initially thought all these needs would drive conspiracy belief, but our findings reveal that unmet needs for control and belonging are the strongest predictors. Here are our main findings:

1. The need for control: People turn to conspiracy beliefs when they feel powerless in their lives. Closely linked to the existential motive, conspiracy theories allow people to explain events as part of a hidden plot, giving them a sense of control – albeit a misplaced one.

Our data show control had the strongest link to conspiracy belief among the four needs we studied. Thus, when people feel powerless, they are more inclined to believe in forces working behind the scenes.

2. The need to belong: Feeling connected to others is essential for our wellbeing. For those who feel isolated or marginalised, conspiracy groups can provide a community that validates their views.

Our data reveal that a lack of belonging significantly increased the likelihood of believing in conspiracy theories. People who struggle to feel accepted may be drawn to groups that share alternative explanations, providing a sense of identity and mutual understanding.

3. Self-esteem and meaning in life: Surprisingly, these needs didn’t play as big a role as we expected. However, among people who experienced increases in their sense of meaning in life over time, we found they were slightly more likely to believe conspiracies at later time points. This finding goes against the idea that only unmet needs foster conspiracy belief and raises important questions for future research.

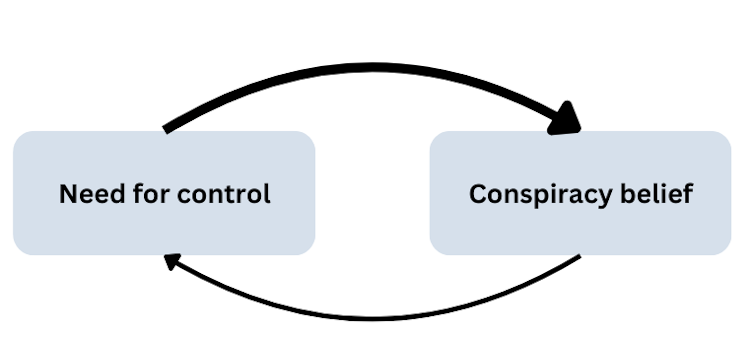

4. Conspiracy belief can worsen unmet needs: We also tracked changes in conspiracy belief and their impact on psychological needs over time. When individuals held stronger conspiracy beliefs, they were less likely to experience control and belonging in subsequent years.

Thus, although unmet needs can drive people toward conspiracy belief, conspiracy beliefs can further erode these same needs, potentially creating a self-reinforcing cycle of mistrust and disconnection.

Learning from longitudinal data

Unlike most studies which provide only a snapshot in time, our research followed participants over several years. This approach allowed us to examine how changes in psychological needs precede shifts in conspiracy belief.

By taking this broader perspective, our results reveal that, although conspiracy beliefs are relatively stable, they can be influenced by feelings of disconnection or loss of control.

Conspiracy belief stems, in part, from unmet needs to belong and feel a sense of control. This helps us understand who may be most likely to believe in conspiracy theories in the future.

Recognising who is most at risk then allows us to develop targeted tools to reduce the allure of conspiracy theories and foster a society grounded in trust and open dialogue. Grasping the “why” behind these beliefs is the first step in building resilience against misinformation in our communities.

The New Zealand Attitudes and Values Study is funded by a grant from the Templeton Religion Trust.

John Kerr works for the Public Health Communication Centre, which is funded by a philanthropic endowment from the Gama Foundation.

Danny Osborne, Elianne Albath, and Mathew Marques do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.