The environmental activist group Extinction Rebellion (XR) recently released its 2022 strategy for fighting the climate crisis, and it looks like the organisation is planning to cut back on antagonising the public this year.

Last year, XR-led protests in central London and across the UK led to disruption, arrests and prosecutions. But in 2022, XR wants to engage with the public based on mutual understanding.

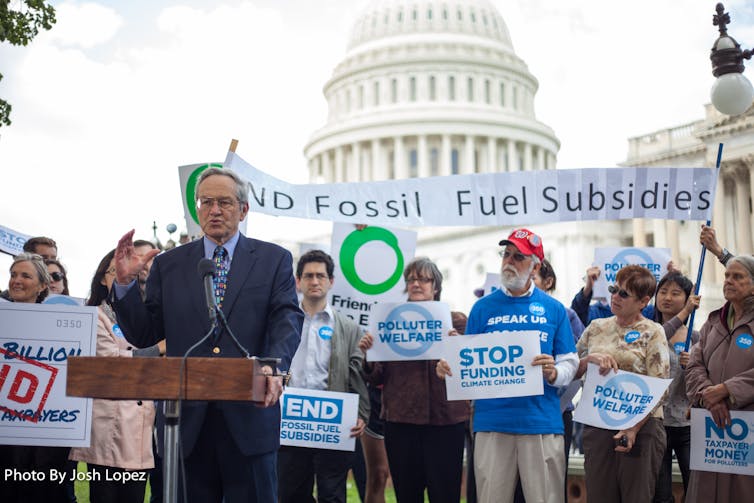

It’s also doubling down on highlighting the need to end the fossil fuel economy. This includes stopping fossil fuel investments, ending new licensing for oil and gas production, and halting subsidies granted to the fossil fuel industry.

Both objectives are challenging. They are also inherently intertwined. Many people still perceive fossil fuels as indispensable to their daily existence, necessary for powering their homes and transporting them around. Demanding that governments simply turn off the “carbon tap” may produce the same antagonism that XR wishes to move away from.

One way for XR to potentially achieve both of these objectives is to focus less on pressuring governments to end the fossil fuel economy, and more on stigmatising the fossil fuel industry.

As our research has found, stigmatisation has already harmed the fossil fuel industry greatly. Just consider the success of the fossil fuel divestment movement, which has resulted in over 1,500 institutions – with assets of almost £30 trillion – committing to divest from fossil fuels since 2012. This movement was even cited by the fossil fuel company Peabody Energy when it filed for bankruptcy.

Likewise, governments including Norway and Ireland, who’ve proposed laws banning investing public funds into fossil fuels, have highlighted the divestment movement as their motivation.

The divestment movement’s end goal is very similar to XR’s – to end the use of fossil fuels – but it aims to do so primarily by convincing the public that the fossil fuel industry is bad. This could be a better tack for XR to take.

Research has, in detail, illustrated how best to vilify corporations. Examples include the successful shaming of industries such as tobacco, weapons, cannabis, pornography and mass tourism. We’ve drawn three main principles from this research that XR could use.

A good source

To attack a group, corporation or industry, those trying to stigmatise them must be viewed as moral or good. This is a difficult one for XR, which has historically prided itself on being disliked.

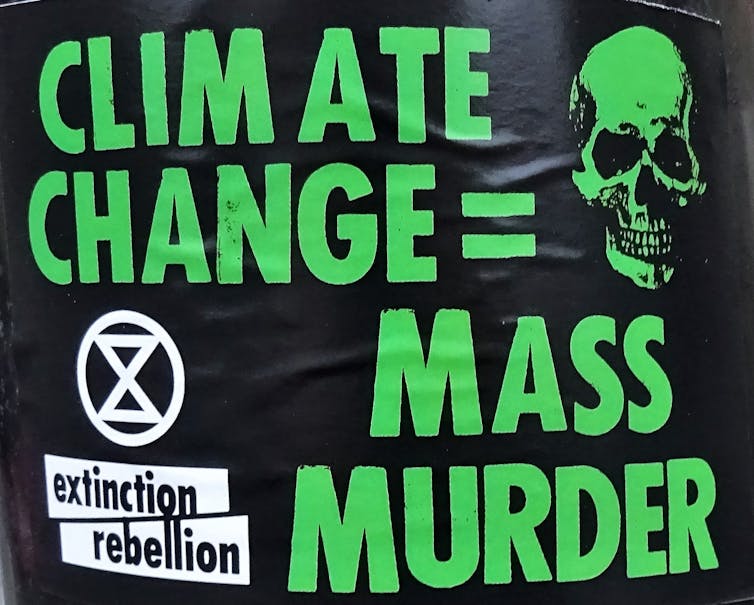

Not only are XR’s actions controversial, but its language is also often negative. XR frequently associates itself with images related to death, such as the skulls that feature prominently in its campaigns.

To change this, XR must connect deeply with the public on an emotional level: preferably by associating itself with historic moral and civic struggles. For instance, XR underplays its remarkable similarities with the suffragette movement. It would help its cause by highlighting the links between itself and the women who fought against oppression.

Our research has shown that climate activists boosted their own perceived morality by demonstrating support for their cause from figures that fought during civil rights struggles. For example, a leader of the fossil fuel divestment campaign, Bill McKibben, associated student activists with apartheid fighter Desmond Tutu, writing:

[Fossil fuel companies] are rogues … students know all this – they understand the grave importance of this battle. They know that heroes of the past, like Desmond Tutu, have joined their voices to the call.

A “bad” target

The targets of any stigmatisation campaign need to be clearly framed as possessing fundamental flaws that are virtually impossible to eradicate. Instead of associating itself with negative imagery, XR’s targets should be intrinsically linked to at least one of what we call the four Ds – destruction, disease, deception and death.

In our study of fossil fuel divestment, a student activist explained the importance of properly assigning blame:

People need someone to blame, like an enemy. It’s the fossil fuel industry … It’s very important that people don’t think it’s their fault. If they do, they won’t want to put up a fight. They will look at themselves and think they should stop driving, and maybe recycle more. This is … total nonsense.

The power of language

Direct, non-violent action to encourage policy change won’t be enough to dismantle the fossil fuel industry’s grip. Instead, XR activists can draw from widely understood negative associations to change people’s perception of the fossil fuel industry from a provider of energy needs to a deviant destroyer of the planet.

The most powerful linguistic device to create stigmatising associations is analogy. Analogies – such as “her eyes are as blue as the sea” – work by making the unfamiliar familiar, by linking an unknown concept (the eyes of someone you’ve never met) to a well-known one (the colour of the sea).

Our study found that climate activists often used analogies to compare the fossil fuel industry with the tobacco industry:

Tobacco companies and fossil fuel companies … both sell highly dangerous products. In a way, the campaigns that stigmatised smoking, especially in the US and increasing in Europe, have done the work for us. We all know smoking is a disgusting habit, so why isn’t burning fossil fuels? It’s a no-brainer.

This comparison tarnishes the fossil fuel industry with stigma related to the tobacco industry: namely that their products cause disease and death, and that, like tobacco, the fossil fuel industry knows about the harm their products cause yet manipulate the public to keep selling them.

Overall, XR’s 2022 strategy reflects a turning point for the organisation. However, maintaining previous tactics – mass disruption and civil disobedience – risks rekindling antagonism. Instead, XR should work on making the public consider fossil fuels as deadly as tobacco.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.