For those who had the opportunity to see the aurora this weekend, it was quite a spectacular moment.

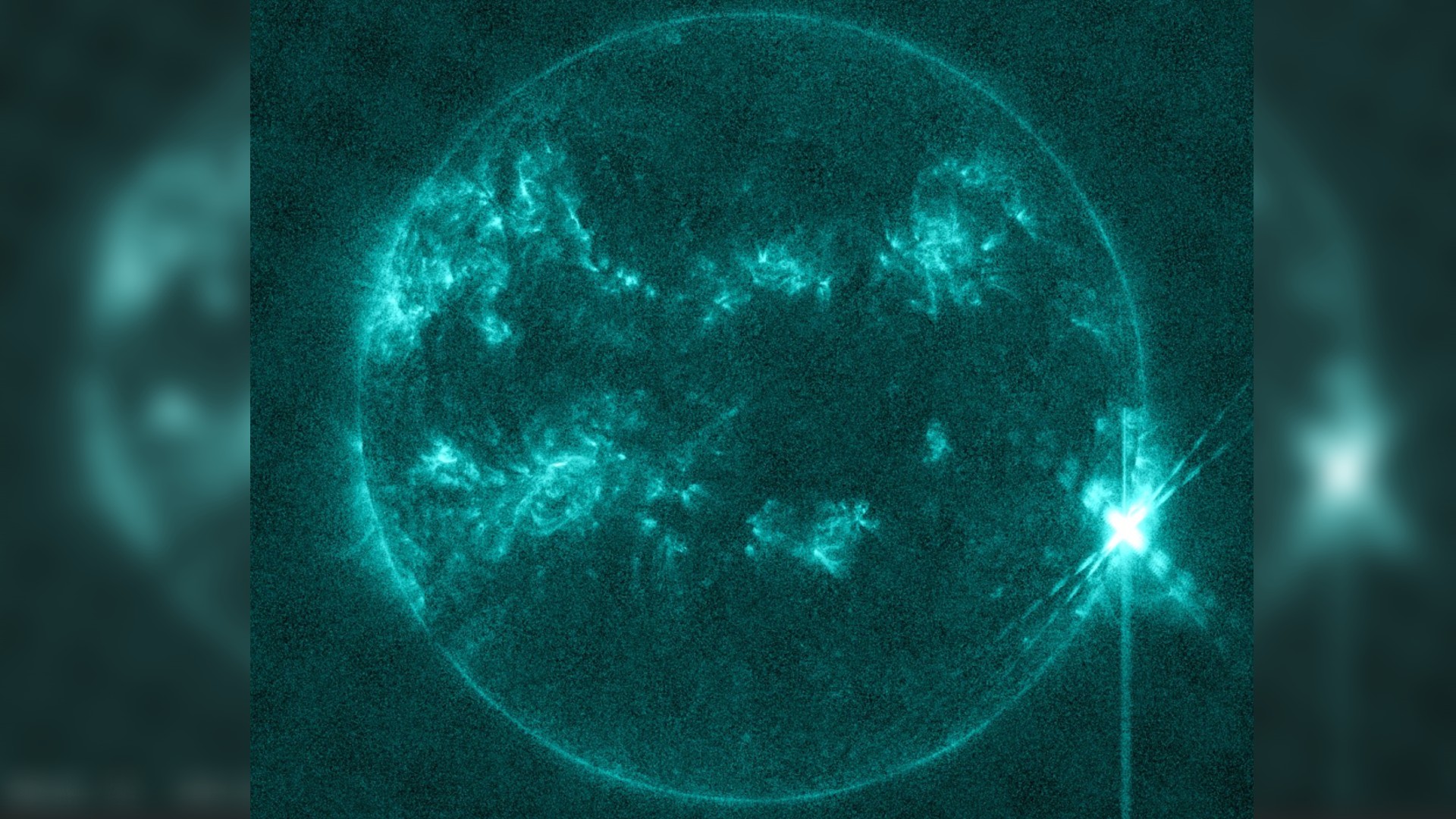

But while seeing the aurora borealis is thrilling and exciting for us, the same coronal mass ejections (CMEs) and geomagnetic storms that make these light shows possible can also wreak havoc on some of the technology that's part of our daily lives.

There was a lot of buzz last weekend about other possible impacts when the historic geomagnetic storms reached the extreme G5 category. Companies that operate satellites like SpaceX reported on Sunday (May 12) on X that "all Starlink satellites on-orbit weathered the geomagnetic storm and remain healthy" and even government agencies like NOAA shared that as of right now there's been no major impacts to their assets.

"We're still gathering information about any impacts, not only to our satellites, but to many other satellites right now," Dr. Elsayed Talaat, NOAA's Director of the Office of Space Weather Observations at NESDIS, said in an interview with Space.com. "We were able to avert and mitigate any disaster because of the warnings and alerts that the Space Weather Prediction Center sent out."

Related: Solar flares: What are they and how do they affect Earth?

As with weather forecasting on Earth, space weather forecasts are just as critical ahead of the storm. That's why NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) continuously shares updates that included alerts, watches, and warnings as new information comes in and changes are made to its forecasts.

"We did really good with the beginning of this storm. We saw the several coronal mass ejections, we figured out pretty close to when they were going to get here. It's 93-million miles from the sun to the Earth so within five to seven hours, we consider that a pretty good forecast. We said it would be G4 or greater and all that worked; everything happened as expected," Bill Murtagh, program coordinator for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC), told Space.com.

The more information forecasters can provide, the sooner power companies can take the preparations needed to prevent disruptions and avoid blackouts and other disruptions. Murtagh also said that part of their job at the SWPC includes making a hotline call to owners and operators of power grids all across the country 24 hours in advance.

"Following a ruling by the Department of Energy, power grid operators have to continue to assess the vulnerability of their assets to geomagnetic disturbances. Upon determining their vulnerabilities, they have to have mitigation plans," Murtagh said. "Some of it involves some engineering solutions like introducing blocking devices to help block that unwanted DC current into the AC network and other activities are simply in response to our warnings where they do different things recognizing their vulnerability. We've come a long way in the last decade to build that resilience."

With every geomagnetic storm that's produced by a CME, there's a threat for anomalies and disruptions to our power infrastructure here on Earth in addition to satellites, GPS, aviation, and spacecraft.

Even though the storm on May 10 reached G5 status, we still dodged a bullet in a way. Solar radiation levels were not as high with this one as we've experienced during previous powerful solar events. NOAA's study for the space weather storm around Halloween in 2003 showed it not only strengthened to extreme (G5) geomagnetic storm levels but also strong to severe levels (S3/S4) on the solar radiation scale.

"These particular storms we never got past a small S2 and that's also a big question mark in our in our abilities to forecast — why are some big eruptions so rich in energetic protons, which is a big issue for satellites and for airlines flying on the high latitude routes for astronauts," Murtagh said.

"We didn't see much of S-scale level type activity and that's also one of those mysteries that we really just don't understand and can't really predict."

Like weather forecasting, there are also limitations in space weather forecasting as Murtagh noted. While there has been so much progress made with predictions, it's still not a perfect science and there's much to be learned from every geomagnetic storm event that happens. Scientists were challenged with the most recent event as there were continuous rounds of CMEs fired off close together which led to forecast complications.

"This is what really got us going over the weekend to speculate and attempt to determine which ones might have arrived and which ones have yet to arrive. And when they did arrive, we had to determine what kind of effect they would have following on the coattails of this extreme event. We just didn't have a good feel for what was going to unfold Saturday and Sunday," Murtagh said.

"Back to the drawing board in some sense; we got some of it right, the important part was giving everyone a heads up that it was coming so they could take action, but as things unfolded, lots to do."

Overall, this event provided important information for future ones of similar magnitude. Plus, learning more about CMEs will also continue to improve aurora forecasts so we can also get a heads up if it will be visible from our own backyards. So don’t give up hope just yet.

"We were trying to get an understanding just how many merged as during the big part of the storm, CMEs would arrive and be kind of masked in the very high elevated solar wind,' Murtagh said. "It was difficult for us to determine which ones were already here and swept past the Earth and which ones had not yet arrived. Also, the last couple of CMEs were not as Earth directed as the previous ones because the sun’s rotating so the sunspots are a little more towards the limb. Sometimes they can hit you hard and sometimes not so I think it was kind of a combination of both that we didn’t see that much Sunday night.

"We have plenty more activity coming from the sun in the coming months and years as we work our way through the solar maximum."