In 1975, Chicano artist Amado M. Peña depicted police brutality by showing the bloodied head of 12-year-old Santos Rodriguez, whom Dallas police had shot for allegedly stealing $8 from a vending machine. The painting “Aquellos que han muerto,” translated as “Those who have died,” further listed the names of other Chicano youth killed by police.

Across the background, Peña included rows of skulls – a gesture that art historian E. Carmen Ramos explains “conjures death and connects with skull imagery frequently used in Mesoamerican religious practices and modern Mexican art.”

Peña’s work was part of what came to be known as the Chicano art movement. Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, Chicano art powerfully decried the discrimination, inequality and cultural oppression faced by Mexican Americans in the United States. At the same time, many Chicano artists threaded symbols of ancient Mexican and contemporary beliefs throughout their political art.

As a professor of Chicano and Latin American art history, I have focused my research on artists’ use of spiritual and cultural symbols to forge a new sense of community.

In particular, over the past few decades, Chicana artists have used the figure of the Virgin of Guadalupe to convey social, cultural and political, though not necessarily religious, messages.

Chicana art and the Virgin of Guadalupe

First, it is essential to understand the centurieslong history of changing practices concerning the virgin’s image.

Today considered the protector of marginalized people, the Virgin of Guadalupe has become an icon in Mexican American social and political movements. As a significant spiritual figure, she is often seen as a symbol of faith, protection and hope.

Known as the dark-skinned patroness of Mexico, legend explains that the Virgin of Guadalupe miraculously appeared to an Indigenous person in Mexico in 1531. Notably, the Virgin Mary took the form of a mestiza, or mixed-race woman, speaking Nahuatl, the language of the recently colonized peoples. Over the centuries, her image came to be associated with vulnerable populations, especially as an advocate for migrants who embark upon uncertain travels.

In the 19th century, Catholic priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla sent the call across New Spain, now Mexico, for independence from Spain. Hidalgo carried Guadalupe’s banner as he gathered fighters. Soldiers wore her image in the battles for Mexican independence of 1810 and again in the Mexican civil war of 1910-20.

In the United States, Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, the leaders of the United Farm Workers Union, carried Guadalupe’s image in the 1960s strikes against the grape-growing companies. National media became riveted by Catholic priests and nuns joining the farm workers who carried crosses and banners of Guadalupe. In this way, organizers within the Chicano Movement affirmed their struggles for economic and racial equity as a spiritual undertaking.

A symbol of empowerment

Through the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, feminist and gender perspectives became more prominent in art as Chicana artists explored complex concepts of identity. Artistic representations of women began to consider intersections of economic class, regional location, gender and sexuality, as well as diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds.

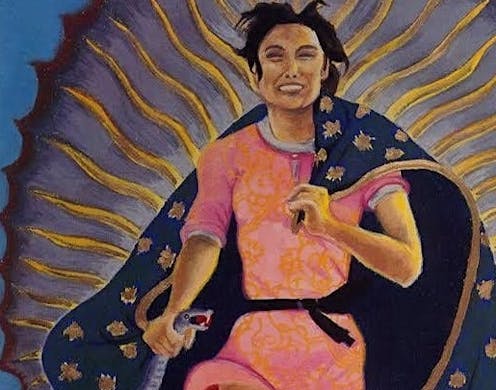

Still, many Chicana artists connected interpretations of the virgin with political and cultural change. Guadalupe was frequently used to express feminist ideals, such as in the work of artist Yolanda Lopez. In her renowned 1978 “Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe,” Lopez appears within the Virgin’s full-body halo. Creating an affirming image of mixed-race women, Lopez modernized the attire by raising the hemline above the knees and adding running shoes. This modern Virgin appears to be vigorously moving forward while boldly clutching a snake as a sign of power and influence.

Chicana artist Ester Hernández also used the Virgin of Guadalupe to symbolize women’s empowerment. In a 1975 print, the artist presented Guadalupe as a karate champion defending the rights of Chicanos. This modern Guadalupe personified the powerful work of women within the civil rights movement.

Protector of the borderlands

Over the past several decades, many Chicana artists have used Guadalupe to emphasize the need for dialogue, solutions and justice in addressing immigration-related issues.

Liliana Wilson, a Chilean American artist well known for her artworks addressing immigration and human rights issues, has worked within borderland Chicano communities for decades. Her 1987 painting “El Color de la Esperanza,” or “The Color of Hope,” features Guadalupe safeguarding a sleeping youth. He is alone and is deeply vulnerable within a desert landscape marked by the barbed wire border fence at his back.

In my recent telephone interview with Wilson, she explained that “the Aztec sun and the virgin are all that the sleeping youth has in this world; they represent his close connection with nature, Indigenous culture and human hope … Guadalupe travels with them in their hearts.”

In a 2010 print, artist Ester Hernández satirically pictured the Virgin within a fictitious “Wanted” poster. The artist used the image of Guadalupe to critique exclusionary policies that endanger migrants desperate for safe spaces.

The poster ironically accuses the Virgin of Guadalupe of committing the crime of “providing limitless aid and comfort” to those who have died attempting to cross the desert regions separating Mexico from the U.S.

Guadalupe as embracing identities

Many Chicana artists and writers use Guadalupe’s image to redefine the borderlands’ people as representatives of a new hybrid space. Guadalupe herself is seen to be a hybrid entity; her apparition occurred at the sacred site previously dedicated to the Aztec goddess Tonantzin, also known as Coatlique, or the “Mother of the Gods.”

For Chicanas, the merging of Tonantzin and the Virgin of Guadalupe is a form of cultural reclamation. It allows them to assert their mixed-race identities while reinterpreting religious symbols to better reflect their diverse experiences and values. Drawing upon this understanding of Guadalupe as a hybrid entity representing the borderlands, in 1995 artist Santa Barraza painted the image of the Virgin on the back of a mestiza (mixed race) migrant and titled the art “Nepantla.”

Nepantla, well discussed within Chicano intellectual and artistic circles, expresses a psychological space of uncertainty and loss, especially within the borderlands. This Nahuatl word represents a state of transition and change, especially as it relates to cultural mixing. For Barraza, this image of Nepantla also represents a historical, emotional and spiritual land – between Mexico and Texas, between the real and the celestial, and between present reality and the mythic world of the ancient Aztecs and Mayas.

Mexican American theologian Virgilio Elizondo has written extensively on such varied ways that the Virgin of Guadalupe represents religious and cultural mixing. Elizondo affirms this blended knowledge that grows out of the borderlands as “existing at the intersection of two ways of knowing.”

In light of constantly conflicting worldviews and systems of power, writers such as Elizondo and Chicana theorist Gloria Anzaldúa present this notion of Guadalupe as a new mestizo sensibility that embraces mixed identities as a means of adaptation and survival.

In Elizondo’s and Anzaldúa’s writings, as well as for many within 21st-century Chicano communities, Guadalupe is the “sign of the new creation,” a third space that accepts the lived experience of difference and supports the needs of those who suffer from social injustices.

Judith Huacuja does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.