Australia’s decision to buy three nuclear-powered submarines and build another eight is so expensive that, for the A$268 billion to $368 billion price tag, we could give a million dollars to every resident of Geelong, or Hobart, or Wollongong.

Those are the sort of examples used by former NSW treasury secretary Percy Allan on the Pearls and Irritations blog, “in case you can’t get your head around a billion dollars”.

Such multi-billion megaprojects almost always go over budget.

For instance, when Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announced the Snowy Hydro 2.0 pumped hydroelectricity project in 2017, it was supposed to take four years and cost $2 billion. The latest guess is it’ll actually take 10 years and cost $10 billion.

So to pay for those two megaprojects alone, there’s an awful lot of money we will need to find from somewhere. Or will we?

‘No simple budget constraint’

In the first year of the pandemic, Australians were given a glimpse of a truth so unnerving that economists and politicians normally keep to themselves.

It’s that, for a country like Australia, there is “no simple budget constraint” – meaning no hard limit on what we can spend.

“No simple budget constraint” is the phrase used by Financial Times’ chief economics commentator Martin Wolf, but he doesn’t want it said loudly.

The problem is, he says, “it will prove impossible to manage an economy sensibly once politicians believe there is no budget constraint”.

A quick look at history shows he is correct about there being no simple budget constraint, despite all the talk about the need to pay for spending.

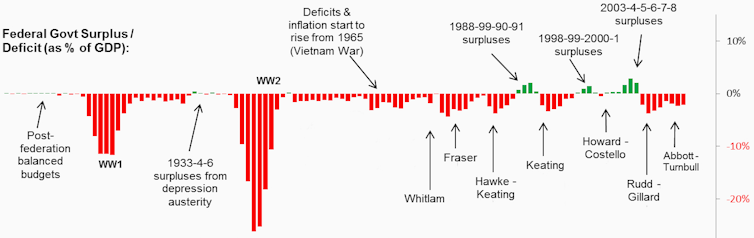

As you can see below, Australia’s Commonwealth government has been in deficit (spent more than it earned) in all but 17 of the past 50 years. The US government has been in deficit for all but four of the past 50.

Commonwealth government surpluses and deficits since 1901

There is no hard limit on how the Commonwealth can spend over and above what it earns, just as there’s no hard limit on how much you and I can spend. But whereas you or I have to eventually pay back what we have borrowed, governments face no such constraint.

Because the Commonwealth lives forever, it can keep borrowing forever, even borrowing to pay interest on borrowing. And unlike private corporations, it can borrow from itself – borrowing money it has itself created.

Governments create money

That’s what the Morrison government did in 2020 and 2021, in the early days of COVID.

To raise the money it needed for programs such as JobKeeper, the government sold bonds (which are promises to repay and pay interest) to traders, which its wholly-owned Reserve Bank then bought, using money it had created.

The government could have just as easily cut out the traders and borrowed directly from its wholly-owned Reserve Bank, using money the bank had created – effectively borrowing from itself. But the Reserve Bank preferred the appearance of arms-length transactions.

And there’s no doubt the Reserve Bank created the money it spent, out of thin air.

Asked in 2021 whether it was right to say he was printing money, Governor Philip Lowe said it was, although the money was “created”, rather than printed.

People think of it as printing money, because once upon a time if the central bank bought an asset, it might pay for that asset by giving you notes, you know, bank notes. I’d have to run my printing presses to do it. We don’t operate that way anymore.

These days the Reserve Bank creates money electronically. It credits the accounts of the banks that bank with it.

One way to think about it (the way so-called modern monetary theorists think about it) is that none of the money the government spends comes from tax.

The government creates money every time it gets the Reserve Bank to credit the account of a private bank (perhaps in order to pay a pension), and destroys money every time someone pays tax and the Reserve Bank debits the account.

If it creates more money than it destroys, it’s called a budget deficit. If it destroys more than it creates, it’s called a budget surplus.

Too much spending creates problems

Can the government create more money than it destroys without limit? No, but where it should stop is a matter for judgement.

If it spends too much money on things for which there is plenty of demand and a limited supply, it’ll push up prices, creating inflation.

Where to stop will depend on how much others are spending.

If there’s little demand (say for builders, as there was during the global financial crisis) the government can safely spend without much pushing up prices (as it did on builders during the global financial crisis).

If it wants to spend really big (say on building submarines), it might have to restrain the spending of others, which it can do by raising taxes.

What matters is what others are spending

But it’s not a mechanical relationship. The main function of tax is not to pay for government spending, but to keep other spenders out of the way.

If the economy is weak in the decades when the subs are being built, the burst of government spending will be welcome, and needed to create jobs. There will be no economic need to offset it by raising tax.

Read more: Explainer: what is modern monetary theory?

But if the economy is strong, so strong the government would have to bid up prices to get the subs built, it might have to push up tax to wind other spending back.

This truth means there’s no simple answer to the question “how they are going to pay for subs?” – just as there was no simple answer to questions about how to pay for a much-needed increase in the JobSeeker, or anything else.

The deeply unsatisfying answer is that, from an economic perspective, it depends on who else is spending what at the time.

Peter Martin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.