Few people played Cosmic Smash, a futuristic, intergalactic sports game that arrived in 2001 during the twilight months of Sega's tragi-glorious Dreamcast saga. But for those who did, the memories have lingered.

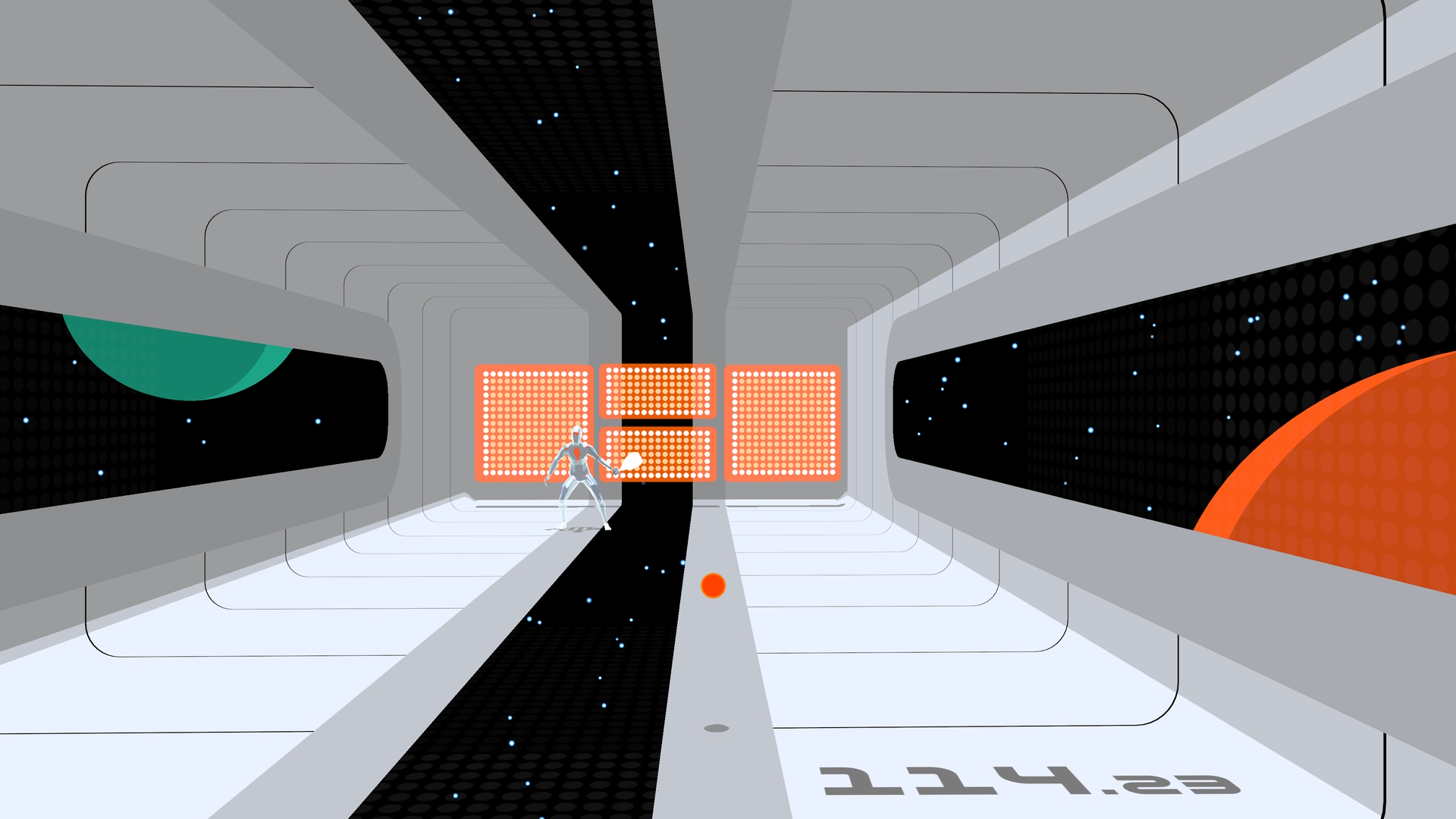

You played as a translucent man, his crunching, stretching wireframe skeleton visible while you chased a molten-red rubber ball around a space-age court, racquet in hand. The rules were enviably succinct: squash meets Breakout. The far wall was constructed from Atari-issue blocks, which vanish on impact. Destroy all blocks before the timer runs out. Ten matches. Final boss (maybe). Welcome to Cosmic Smash.

Rez's lithe, athletic cousin, Cosmic Smash launched a few weeks ahead of Tetsuya Mizuguchi's trance masterpiece. Both games matched their laser-beam aesthetics with the sort of treble-heavy electronica that could pierce a cloud of cigarette smoke. Of the pair, Cosmic Smash was the more basic proposition, but it also showed a world bewitched by lavishly textured 3D games that gaming's arcade heritage remained as urgent and legitimate as any high-production open world.

At the time, Jörg Tittel was a theatre student studying in New York, freelancing as a game journalist when he learned about Cosmic Smash via screenshots published in Famitsu DC, a Japanese magazine to which he occasionally contributed. He ordered a copy from Japan, the only territory in which Sega released the game (it had debuted in Japanese arcades a few months before the Dreamcast release).

The disc arrived several weeks later, tucked snugly inside a semi-transparent milky DVD case that, when placed on a bookshelf, stood tall and awkward above the rest of the Japanese Dreamcast's uniformly sized CD boxes.

"The Dreamcast was to me the birthplace of the indie scene."

Jörg Tittel

"I just loved it," he recalls. "The design was stunning – everything about it." Something, however, was missing. Tittel claims that at the time he thought Cosmic Smash seemed perfectly suited to virtual reality, the technology Sega helped pioneer in the early '90s, then swiftly discarded due to cost and technical challenges.

"This is the tragedy and the genius of Sega," he says. "They've always been just a little bit too ahead of their time, right? Always just overshooting a little bit." To Tittel, the Dreamcast version of Cosmic Smash seemed to be a teaser for a fuller-bodied, more immersive experience – one perhaps found in an alternate timeline where everyone in the world owned a Sega-brand VR headset.

Tittel graduated and, after a brief stint working as a writer for Treyarch, moved into a career in film and theatre. Witnessing the explosion of indie games in the late 2000s, he was reminded of the spirit of the Cosmic Smash era. "The Dreamcast was to me the birthplace of the indie scene," he says. "You had developers working within Sega, but who were also incredibly independent, actively encouraged by the leadership at Sega to make the games they wanted. They didn't necessarily have the marketing money to back them, so the concept, the passion, the artistry had to shine, much like with indie games today."

Then, with the arrival of affordable VR headsets, Tittel remembered Cosmic Smash. He began to wonder whether it might be possible to persuade Sega to bring the game to virtual reality, the realm in which he believed its truest form had always belonged. Securing the rights – even to an obscure game for a dead console – from a company notoriously protective of its IP was going to be a difficult trick shot to pull off.

Making a racket

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more in-depth features interviews delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge magazine.

The original Cosmic Smash was the smallest game built by Sega Rosso, the most modestly sized of Sega's internal development teams.

"The mainstream at Sega at that time was to develop games with [large] numbers of staff, over a long period of time, at a great cost," recalls Kenji Sasaki, Sega Rosso's founder and the executive producer of Cosmic Smash. "This approach had its advantages, but also significant disadvantages: decision-making was slow due to the number of people involved, and staff who conceived of new game ideas couldn't be properly nurtured." Young people, in particular, struggled to have their ideas heard, Sasaki says.

With Sega Rosso, Sasaki wanted to gather a small but elite group of staff who could work on smaller projects, with shorter development cycles. By outsourcing extraneous elements of the production, Sasaki sought to "create an environment in which young staff could freely come up with ideas and develop them". The intent was to erode the kinds of hierarchies that can stifle creativity at mature companies, and promote younger, fresher perspectives. (Sasaki himself had directed Sega Rally Championship while still in his twenties.) "If we could devise a good plan, we would adopt it and launch the project regardless of [the originator's] position."

Cosmic Smash was one such idea, mooted by a young CG artist, Toshiaki Miida, who had modelled and animated the crowds in the Sasaki-directed Sega Rally 2. Running an autonomous internal studio, Sasaki did not need to seek approval from anyone else at Sega; he was free to pick the projects on which he and his staff would work, and sign off on all costs.

"We decided that the game had to have strong emotional elements, such as exhilaration and intuitive playability," Sasaki recalls, "so we assigned a young and talented programmer to create a prototype to verify the fun factor."

To help speed up production, the music was provided by outside composers, while the team licensed technology from the developers of Sega's flagship arcade sports game, Virtua Tennis, to provide the basic ball physics and character movement. The block-destruction mechanic was produced in-house via a trial-and-error process. Marrying the two mechanics – squash and Breakout – took time to perfect, a process that extended the development period, but not significantly. "I think our style of developing slowly with a small number of people suited this project well," Sasaki recalls. In January 2001, less than a year after Sega Rosso's founding, Cosmic Smash launched on the Naomi arcade hardware.

Prior to the game's release, the reaction among other departments at Sega was, Sasaki says, critical. The concept was considered too simple, the style too unadorned. In the arcades, however, players warmed to a game that was well suited to short bursts of play, and striking to watch. The team visited local arcades to observe the public while they played. "We were happy to see that the majority of people were playing intuitively, as we had hoped."

The home console version of the game, however, arrived with no contextual advantages. By the time of Cosmic Smash's Dreamcast launch, Sega had announced the closure of its console business. The team, which had initially had its unconventional request to use a DVD-style slipcase turned down, had the decision reversed. No one at Sega seemed too bothered about such trivialities by this point. Sega Rosso closed and, aside from a few stalwart international fans who imported the game from Japan, Cosmic Smash was largely forgotten.

"The mainstream at Sega at that time was to develop games with [large] numbers of staff, over a long period of time, at a great cost."

Kenji Sasaki

By 2019, Cosmic Smash's clean, hopeful styling embodied a long-vanished Sega – but one that had persisted, unageing, in the minds of a certain kind of videogame player. Tittel approached Sega to ask whether he might secure the rights to remake the game, or an updated version, in virtual reality.

"The guy I spoke to from Sega told me that he had never heard of Cosmic Smash before," Tittel recalls. "I made further inquiries, and no one seemed interested in engaging in that conversation. Maybe it was too small to be on their radar, or maybe they felt it was a waste of their time. Who knows?"

Undeterred, Tittel approached staff within Sega who were more connected to the Dreamcast era. He decided to create a lavish presentation, one that would communicate his vision for the game, as well as demonstrate his passion for it and the era from which it emerged.

For his dream project, he assembled a dream team. Graphic designer Cory Schmitz (who has since joined PlayStation Studios) would evolve the original game's stark, handsome UI elements and branding. Rob Davis, the comic-book artist behind The Motherless Oven and Don Quixote, would provide art direction. For the soundtrack, the director approached Ken Ishii, the Japanese DJ and producer whose music featured in Rez, and the London-based composer Danalogue, whose pristine beats he believed would sit perfectly alongside Ishii's work.

The presentation, voiced by Tittel, who assumed an American accent for the recording, concluded with a spirited appeal. "During the last 20 years, more and more people have been dreaming of a return of Cosmic Smash," he said. "Please help us make this dream come true." It worked. Tittel was granted the VR rights for a new game set within the Cosmic Smash universe.

There were provisos. All music, sound effects, art and assets would have to be recreated from scratch, and Tittel would not be allowed to use the exact name 'Cosmic Smash' – a rather bewildering restriction. But he remains philosophical about it. "If you go back to the Dreamcast days, there would be a Jet Set Radio and a Jet Grind Radio, and people knew they were of the same family…"

With the relevant permissions in place, Tittel wrote to the original game's executive producer, Sasaki, to seek his blessing and involvement. "He was the first person I reached out to when the project was starting to become a reality," he recalls. "I would never want to work on a game purely on a 'licensing' basis. And at the very least I wanted to ensure that its original creators knew how much I deeply respect their work."

Sasaki was surprised to hear from a western filmmaker about his plans to resurrect the game – but not by the revelation that Cosmic Smash was now destined for VR. "Even before I heard about this remake project, I had thought that if we ever remade Cosmic Smash, it would be in VR," he says. "I was surprised and happy to be asked." Sasaki hoped to put Tittel in contact with Toshiaki Miida, the 3D artist who devised the original Cosmic Smash, but was dismayed to find that neither Sega nor his former colleagues at Sega Rosso had any contact information for him. "It is my one regret," Sasaki says now.

Return Smash

"The guy I spoke to from Sega told me that he had never heard of Cosmic Smash before."

Jörg Tittel

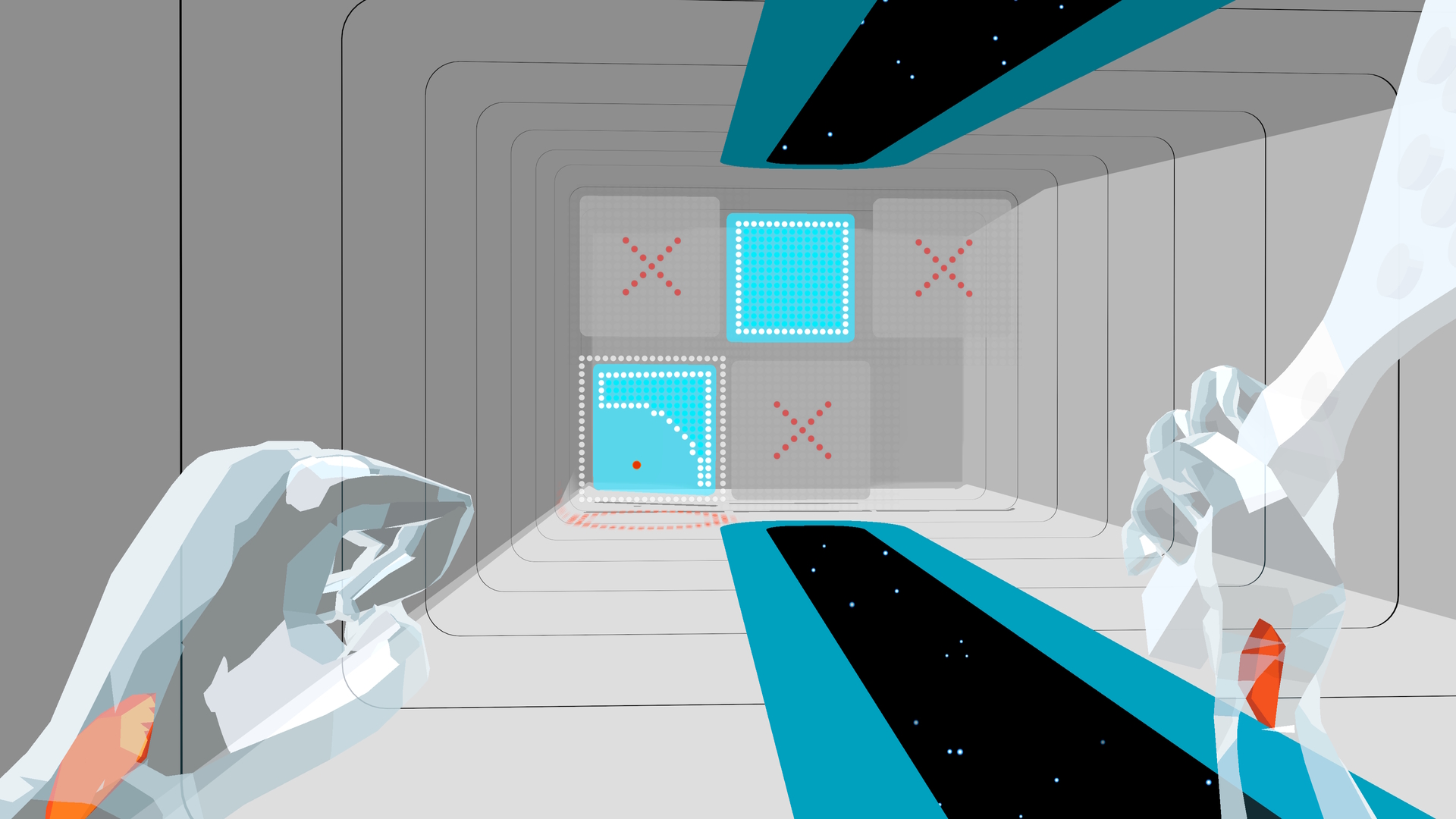

C-Smash VRS, as the sequel is named, has retained all of the stylish character and charm of the original. Set to launch this spring as a PSVR2 exclusive, it feels like a natural fit for Sony's hardware. And a useful one, too, helping – alongside a fresh port of old stablemate Rez Infinite – to diversify an early lineup that might otherwise lack the the kind of stylish, club-culture-adjacent projects that have long been a crucial element of PlayStation's identity (at least outside of North America's more vanilla context).

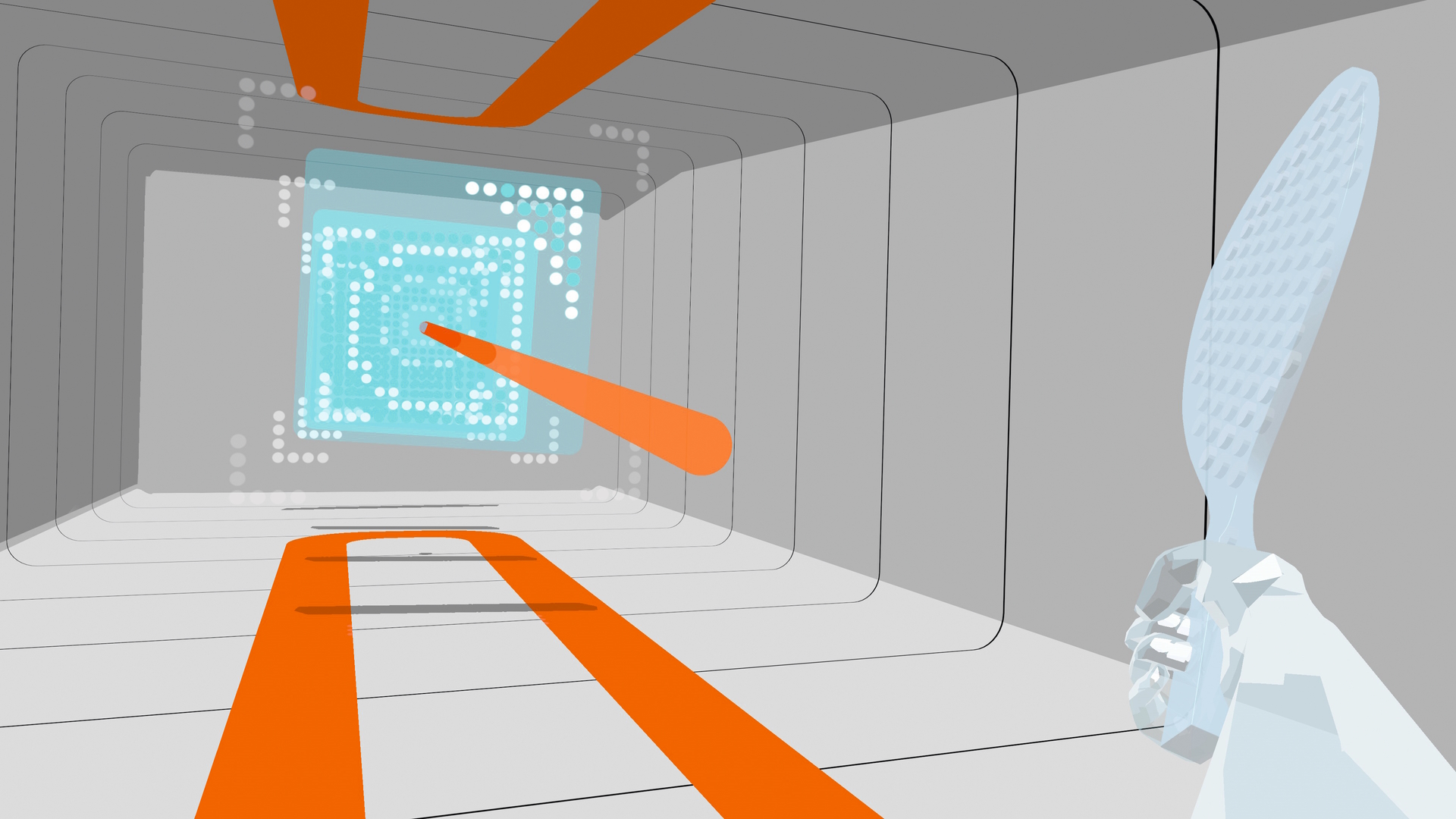

In play, the courts feel larger and longer than those seen in the flatscreen original (the roof, too, has been imperceptibly arched, to ensure arcing shots follow a pleasing trajectory), but the hardware eliminates one of the original game's issues: the imprecision of control. Now, with PSVR2's Sense controllers mapping every tilt and swipe of the racquet exactly, it's possible to angle and direct each shot with agreeable accuracy.

Running around the virtual court in your living room and leaping into the air for trick shots would, as Tittel jokes, not be the kind of 'cosmic smash' the team is looking to offer. Instead, movement is controlled via the analogue stick, while high balls can be drawn toward you using a sort of tractor beam.

Here, VR's essential trick, of giving you an authentic sense of being in an imagined space, is utterly convincing, despite the abstracted science-fiction setting. In competitive matches, you can look your opponent up and down as they stand alongside you, while your teal racquet feels almost weighty in the hand.

The game benefits from the fact that you are often encouraged to aim the ball high, to eliminate blocks at the top of the wall; unlike in tennis, where lob shots can be punished by an opponent, every part of the virtual space is relevant and important.

"There's no shaming here. We want everything to feel light-hearted and good-spirited."

Ryan Bousfield

While the game's online versus mode is where Tittel and the team believe the game's potential longevity resides, the atmosphere around C-Smash VRS's competitive modes is neither boisterous or charged. Everything about the setting, coldly minimalist as it might first appear, has been designed to be warm, welcoming and mutually supportive.

"Blockbuster videogames constantly make you escape into worlds that hate you, that want to kill you," says Tittel. "It's like an abusive relationship. Who wants to go on holiday to a country where everyone wants to kill you? We wanted to create a world that is welcoming, even consoling."

The game is set on a space station – a giant, spinning version of the game's logo. It's a utopian place, whose inhabitants (based on the characters seen in the original's end credits) quietly go about their chores, growing flowers, maintaining the building and so on. In the singleplayer story mode the player is shuttled between matches on the cosmic shuttle bus (another flourish lifted from the original), which gives the game a sense of sweet and gentle momentum: the texture of a leisure tour rather than a competitively charged tournament.

"We didn't want an unnecessarily competitive spirit," says Ryan Bousfield, director of Wolf & Wood Interactive, the studio that partnered with Tittel to develop the recent dystopian satire The Last Worker, and has done so again to make this game. "Or, you know, show your character crying if you lose a match. There's no shaming here. We want everything to feel light-hearted and good-spirited. That is something that we're trying to do at every point."

These warm-hearted vibes were important to communicate via the soundtrack, too, we're told by composer Danalogue: "I wanted to bring energy, propulsion, excitement and a rising intensity as the levels increase in difficulty, but also to sonically allude to a feeling of psychedelic transcendence – that this is more than a test of physical prowess, but an integral part of a deepening evolution of consciousness in an imagined future society," he says. "I also tried to create a sense of weightlessness in the sound, capturing the feeling of floating out there in a space station, and using high-frequency sounds to hint at the stars glimmering all around."

The team also has a broader philosophical point to make. As the player progresses through Journey mode, each stage becomes increasingly spartan; the furnishings of the play space are removed, revealing ever more of the cosmos behind the walls. "The idea is that it's not a threatening world, it's a relaxing world," Tittel explains. "But the reason everyone is so relaxed is because they also realise that they are at the end of time, at the end of space. Maybe that's the kind of feeling that we all feel a little bit on our planet right now. Except we seem to be responding with greed and hatred." C-Smash VRS, he says, presents an alternate vision of human life at the end of time, a place where "you would try to be good to yourself and to each other, hanging out, listening to music, having a good time. That's what it felt like to be a Sega player as a kid."

Of course, a certain amount of conflict does await the player. The original game featured a secret boss – only encountered if you won every match using a final trick shot – who would fire volleys of balls at you. In C-Smash VRS the final boss is simpler to access but no less intimidating: a black hole draws the space station toward it, gradually stripping everything away, against which you must fight in the final, cosmic showdown.

Warm soul

For all Tittel and the team's philosophical ideas about mutual support and encouragement at the end of time, C-Smash VRS will feature a range of competitive modes. As well as straightforward head-to-head matches – which can be experienced in the game's demo, currently available on PS5 – there will be a variety of other rulesets. Among them is Firewall, in which the aim of the game is to turn the colour of the blocks to your side's colour by targeting them with your ball, while your opponent fights to secure the majority before the timer runs down. The team is still playtesting other modes, including one in which a player must protect their body from the ball (working title: 'Bodysmash'), and they plan to listen to suggestions from the community, with the intention of introducing new modes post-launch, to go alongside new music and other downloadable treats.

Like the original game, C-Smash VRS has enjoyed a short, intense development period. Assuming the game launches on time in the spring, it will have been made in less than a year, built using Unity and some new, bespoke netcode. There was no equivalent to the Virtua Tennis engine the team could borrow from a friendly group of developers down the corridor. "We've had to build the physics from scratch just to get, like, really low latency on the networking side," Bousfield says, "but it just means that we can get the tightest interactions over a network, without worrying about having some middleware in between."

As well as Journey mode, and online Versus modes, the team has implemented an 'Infinity' mode, in which the player can freely bounce the ball back and forth off the far wall, while listening to a dynamic soundtrack. For Tittel, this freewheeling mode represents the warm soul of Cosmic Smash, and it is where he hopes some players will spend most of their time. "Technically it could be referred to as 'Fitness mode'," he says. "But I personally feel stressed by the prospect of having to work out – being told 'You have to get fit', or 'Here are your metrics', you know? I hate that stuff. So, while we will have some stats in the game, on the top level we want to strip everything back so you can just enjoy being in it and enjoy the music. Enjoy the mechanics. Enjoy the feeling of Cosmic Smash."

This feature first appeared in Edge magazine issue 382. For more fantastic in-depth features and interviews like this, you can pick up single issues at Magazines Direct or subscribe to the magazine, in physical or digital form.