Brock Purdy came out of Iowa State built a little bit too much like a fullback. He has humongous quadricep muscles, which, as a thrower, placed him on his toes more frequently and forced him to draw energy from muscles you wouldn’t ideally call upon in a passing motion. He was, in a clinical sense, a bit “pushy.”

It’s safe to assume that evaluators saw this and his relatively small stature for the position (6' ⅝" at the NFL combine). And, considering his massive body of work—46 career starts for the Cyclones—they were able to determine that they knew all they needed to know about a player they probably weren’t going to select in the 2022 NFL Draft.

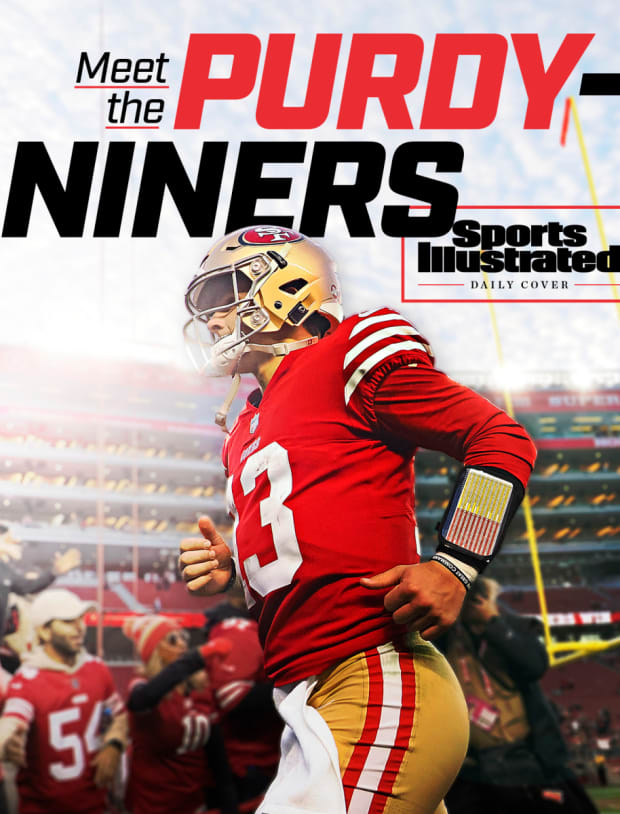

Kelley L Cox/USA TODAY Sports

But Purdy also came out of college brilliant. There is a proprietary cognition test some teams and trainers use in order to get a better understanding of how a player’s brain works—it measures functions such as impulse control, which have a direct correlation on how likely they are to throw the correct routes in correct situations. Purdy rated as a starting NFL quarterback. He had a library of experience and situational learning in the pocket.

He also came out eager to try something new. Most of the time, draft prospects are shoved through conveyor belt trainers to prepare them for their All-Star game, combine and pro day; they focus on things such as the 40-yard dash, the shuttle runs, the bench press, the live throwing drills and the board work with teams in private meetings. It’s a collection of experts who are seemingly disconnected, and most prospects treat them that way.

But the idea of a holistic suite of pre-draft performance training regimens piqued Purdy’s interest. What if so much of it was actually interconnected? What if he spent the days between his final collegiate game and his draft day with a bunch of baseball players, an Australian-born QB guru and a workout room that could, at times, ask him to lift less than the weight of a football? What if the fullback became just a little bit more of a quarterback?

“This was one of the largest measurable increases in performance that we’ve ever seen,” says Will Hewlett, the guru, and a house expert of QB Collective (an expansive think tank founded by a former NFL player-turned-agent, Richmond Flowers, with connections to NFL coaches like Mike McDaniel, Matt LaFleur, Kyle Shanahan and Sean McVay). During the draft process, Hewlett says he added roughly 5 mph to Purdy’s pass, which, had the quarterback been a baseball player, could have easily triggered an investigation for performance-enhancing drug use. “It got to the point where NFL organizations said, What on Earth did you do?”

That last line is a bit of a loaded question, especially when it comes to Purdy. A few months ago he was the NFL Draft’s Mr. Irrelevant, the final selection at No. 262. He earned a spot as the 49ers’ third-string quarterback. Now? He is stepping under center for one of the NFL’s elite teams, and that fact doesn’t seem to be freaking anyone out (most betting markets, as of this week, have San Francisco as the fifth-most popular team to win the Super Bowl).

This is a story about what on Earth they did on a small scale. It’s also a story about what they might have done on a larger scale, and whether there is evidence that you can take one of the draft’s most available resources—quarterbacks who are sharp processors with a robust hard drive of in-game experience but aren’t reminiscent physically of the league’s best quarterbacks—and turn them into one of its most potent weapons.

The process of giving Brock Purdy a better fastball started with the quarterback encircled by 3-D motion capture cameras, which track and lay out every aspect of his throwing motion. Here is what the cameras found:

• He created too much elbow extension and elbow flexion as he brought his arm up.

• He needed to settle into a better pre-pass stance, which involved dropping his hips and engaging his glute muscles.

• He was not drawing nearly enough from his hip muscles on the throw.

• His backstroke was elongated.

• His front arm had too much movement and was not connected to the throw.

Once they identified the inefficiencies in his motion, Hewlett and a partner, physical therapist and clinical specialist Dr. Tom Gormely, embarked on a complementary weight and throwing program designed to safely expedite an eight-week improvement over the course of four or five weekly sessions.

Jasen Vinlove/USA TODAY Sports

In the weight room, Purdy would start with a heavy, explosive movement designed to make his body feel the changes that Gormely and Hewlett wanted him to make, or what they called “base” movements. An example: a landmine pull to press, which involves a person standing next to a bench press bar with weight on it, gripping the outer portion of the bar, lifting it up with one hand and pushing through the bar with the other hand as the lower body rotates through, almost as if the person is throwing a shotput.

“I have to fix the constraints that are limiting him from producing high levels of force early on,” Gormely says. “I can’t just tell him to rotate really fast if he can’t rotate yet. We’re starting to teach him with heavier, plyometric drills the arm pattern and path and sequence that we want to produce quickly later.”

In those beginning days, Purdy was working on small, technical aspects of the throw that do not involve uncorking a new motion (like the rhythm of his feet in a drop back). But as the weight of his gym work began to drop and incorporate lighter and faster movements, the speed and the volume of the on-field throwing began to increase.

An example of a two-day stretch of time:

Monday weight room: “Overloaded” ball day, where, in the weight room, Purdy is using a heavier ball and focusing on exercises designed to improve his arm path and the sequencing of movement through his pelvis. In addition, there is a heavier lower-body lift focusing on the stability of his “base.”

Monday on field: Very low-volume throwing session.

Tuesday weight room: Aggressive, lower-body rotational velocity workout. The workouts are designed to make Purdy feel what it’s like to methodically accelerate through his spine and pelvis, while keeping that movement tied to his arm (one example is the delightfully cathartic-seeming “run and gun” medicine ball toss, in which a person sprints up to a point and hurls a weighted ball at the wall). A lot of “underloaded” or light weight (less than that of a football) work to make him feel the speed of his arm repetitively. Sometimes, players can use a towel, for example, while flapping their arm back and forth.

Tuesday on field: Route trees where arm speed and velocity are required, cementing what he has learned from a muscular standpoint in the gym.

“Brock worked his ass off,” Gormely says, summing the process up.

Gormely and Hewlett would stay in touch or, often, attend each other's sessions, which made working on Purdy a kind of live-editing process. Gormely would tell Hewlett what they were working on in the gym and what to look for on a throw, and Hewlett would report back to Gormely on what he saw during the throwing sessions that may require more attention and focus in the gym. Then Hewlett, through the QB Collective could refine the expectations of Purdy at the next level, asking pro coaches for their thoughts, ensuring that they were not drilling anything extraneous to modern offenses.

They also saw Purdy enjoying the idea of immersing himself into the lives and habits of throwers. Gormely got his start in baseball, so the facility was swarmed with major league and minor league baseball players during their concurrent offseasons. Among them were Orioles pitchers Mike Baumann and Tyler Wells.

“He would sit down and be like ‘Big Mike, what are you focusing on when you’re pitching on the mound? What are you doing with your rear leg?’ He was trying to pick up little things. Like, Mike throws 100 miles per hour. Brock wanted to know ‘How do you generate so much force?’ They would sit there eating lunch and chop it up. That inquisitiveness makes him special. He wanted to learn.”

By the time Purdy arrived at the Shrine Bowl, a little more than a month after his final collegiate game (a loss to Clemson in the … clears throat … Cheez-It Bowl), it was clear he was in the process of refining his identity as a thrower into more of what we see now. For instance, late in the first half last Sunday against the Dolphins, when facing an unblocked edge rusher barreling toward him, he rifled a ball to George Kittle over the middle to pick up a critical first down. The whipping motion of his arm took just a split second. The ball cut through a zone of four defenders.

In his first NFL regular-season game, Purdy was 25-of-37 for 210 yards, two touchdowns and an interception. His snap-to-throw time, 2.67 seconds, was among the fastest for quarterbacks in Week 13.

“I know he was going through a transition in terms of what he was doing,” says Eric Galko, the director of football operations and player personnel for the Shrine Bowl. “He was starting for four years—why change what was working? But he knew he wasn’t a finished product despite being in school and playing as well as he did.

“He’s a guy that kind of suffered from NFL teams’ eyes from what I call ‘over-evaluation,’ where they kind of knew what he was for so long that they kind of said ‘Eh, that’s Brock Purdy.’ But we thought he was not dissimilar to a player like Baker Mayfield who, a few years ago, went No. 1 overall in the draft.”

Adding to Galko’s optimism was the obvious: “It looked different. And to be that different, to show you can improve in just a couple of weeks, see that kind of development, there was a lot of room for him to get better.”

Jim Dedmon/USA TODAY Sports

It brought up an idea that is rarely touched on in a macroeconomic sense. At the moment, due to an increase in the quality and availability of athlete training and nutrition everywhere, we are at a point in the NFL where there are more incredible outlier-type skill-position players entering the draft each year. Since 2018 alone, we have seen Saquon Barkley, Nick Chubb, Mark Andrews, Deebo Samuel, A.J. Brown, DK Metcalf, CeeDee Lamb, Justin Jefferson, Jonathan Taylor, Ja’Marr Chase, Jaylen Waddle and Kyle Pitts, just to name a small handful.

Why are we wasting so much pain and effort in finding quarterbacks who look like Josh Allen or Patrick Mahomes, when they are harder to find than a humble Twitter account? Why are we assuming that someone like Purdy can’t get better, good enough to feed the glut of talent at the position currently blooming across football?

This theory ignores what Hewlett and Gormely both brought up independently, that Purdy is himself a special kind of outlier in his own right, and possesses the kind of intelligence and leadership abilities that allow him to climb into this position in the first place. Indeed, 49ers tackle Trent Williams told a reporter this week of Purdy: “You would think he’s Peyton Manning or something” given the comfort with which he goes after far more experienced, veteran teammates.

If that’s the case, perhaps there’s something to be said for the 49ers’ hope in a seventh-round rookie, and for the kind of prospect who knows himself well enough to realize that, even though he might be good enough to make the NFL, he can still relearn to throw a fastball.