The August 2023 issue of Sports Illustrated features The Power List, the definitive index of the 50 most influential figures and forces who drive the sports world, on and off the field and court.

“You know what’s funny?” Jake Paul asks, directing the question at no one in particular. It’s early May, and Paul is in Dallas, corralled in a locker room in American Airlines Center. A pair of cameramen, there to capture Paul’s movements before a press conference to promote his August fight against former UFC star Nate Diaz, sit across from him. Brandon Amato, Paul’s creative director, is flipping coat hangers onto hooks in a corner. Eventually, Paul’s gaze settles on Marcos Guerrero. In 2019, Paul, then fully immersed in the YouTube world, hired Guerrero as an editor. When Paul pivoted to boxing, he told Guerrero he wouldn’t be producing as much content. He asked whether Guerrero had ever been an assistant. As training for the job, he sent Guerrero to shadow the assistant for Paul’s brother, Logan. After a few weeks Guerrero was ready. His first task: Fire Paul’s existing assistant.

“Donald,” Paul says, answering his own question. “Nate’s middle name is Donald.” He nods his head, channeling Eminem’s final freestyle in 8 Mile. “This guy’s a gangster, his real name’s Donald,” Paul raps. As a boxer, the 26-year-old Paul is a novice. As an irritant, he’s a seasoned pro. In 2021, Paul sparked a brawl after swiping a hat off Floyd Mayweather’s head at a press conference to promote Mayweather’s exhibition match against Logan. Months later, before a scheduled fight with Tommy Fury, Paul offered to pay Fury $500,000 if Fury beat him. If Fury lost, he would have to legally change his name to “Tommy Fumbles.” When Fury’s girlfriend, influencer Molly-Mae Hague, posted a photo of the couple holding their newborn, Paul hopped in the comments, writing, “Just in time to watch your dad get knocked out.”

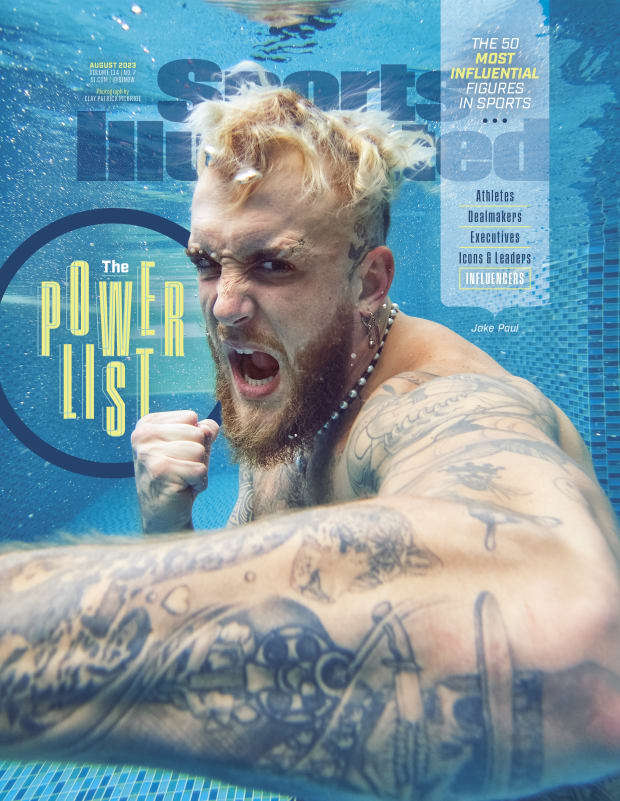

Clay Patrick McBride/Sports Illustrated

Bets, Paul has discovered, tend to resonate. Before his first fight with Tyron Woodley, Paul insisted that the loser get a tattoo declaring his love for the winner (Woodley, after getting out-pointed, had I LOVE JAKE PAUL inked to his middle finger). It’s an attention-grabbing tactic Paul has noticed others borrowing. Weeks before facing off in March, Gervonta Davis challenged Ryan Garcia to bet his purse. “And that’s all anyone was talking about,” says Paul. “It gets mainstream attention. It sticks.”

As Paul speaks, his manager, Nakisa Bidarian, pulls up a chair alongside him. Bidarian, a stoic, Stanley Tucci type, is partners with Paul in Most Valuable Promotions, a promotional outfit, and the unofficial head of Jake Paul Inc. He wants to talk business. “Is that orange Celsius?” Bidarian asks, pointing to an unopened can on the table. In recent years Bidarian, a former UFC exec, has spearheaded the effort to evolve Paul from volatile YouTuber to a more corporate-friendly product. Celsius, marketed as a healthier energy drink, recently signed Paul to a long-term endorsement deal. The goal is for other big brands to be right behind them.

The conversation shifts to the Diaz fight. Specifically, which celebrities will show up. Paul rattles off a list of possibilities. Aaron Rodgers. Jack Harlow. Lolo Jones. Joey Bosa. Nick Bosa. During fight week, Paul suggests Luka Dončić, the Mavericks star, host some events. Paul’s gargantuan social media following—20 million subscribers on YouTube, 23 million followers on Instagram, another 17 million on TikTok—affords him an endless list of contacts.

When the press conference begins, Paul slips into character. He pulls a clapping toy monkey out from under a table. “I think this is what’s going on in Nate’s brain,” he says. When Diaz speaks, Paul looks at him quizzically. “I don’t speak Stockton,” Paul says, referencing Diaz’s central California hometown. A member of Paul’s entourage, posing as a reporter, grabs a microphone.

“Derek from Betr Media,” says Derek Sullivan, a content creator for Betr, Paul’s microbetting site. “Nate, I’ve been trying to get on this undercard. I was wondering if I could fight your brother, Nick. If he’s anything like you I think I’d beat his f---ing ass.”

CHANDAN KHANNA/AFP/Getty Images

There is one serious moment. When a reporter asks Diaz whether he has confidence knowing he wouldn’t be sharing the ring with a Hall of Famer, Paul bristles. “I don’t know who you are to say I’m not a future Hall of Fame boxer,” says Paul. He continues: “I’ve done more for the sport than any boxer in current history. What’s Floyd Mayweather done for women’s boxing? I’ve changed the entire game. I’ve brought a new 70 million followers to the sport. I’ve put on bigger pay-per-views than some of these ‘Hall of Fame’ guys. . . . And I just got started.”

Skeptics of Paul’s commitment to fighting have long vanished. Last February, Paul took the first loss of his career, a split-decision defeat to Fury. He didn’t quit. He doubled down. He shook up his team, bringing back Shane Mosley, who trained Paul for his first pro fight. In Puerto Rico, where Paul has lived since 2021, Paul built a gym out of an abandoned medical supply building, where experienced pros like J’Leon Love and Rydell Booker provide regular sparring. In August he will face Diaz, part of a multifight plan that includes a rematch with Fury and an all-influencer showdown with KSI. “I think he’s genuinely got the boxing bug,” says Eddie Hearn, who promoted Paul’s first pro fight. “He’s fallen in love with the sport.”

Clay Patrick McBride/Sports Illustrated

On the business side, Paul has elevated Amanda Serrano, a seven-division world title holder whose profile—and bank account—has swelled significantly since signing with MVP. Last spring, Paul copromoted the lightweight showdown between Serrano and Katie Taylor, which sold out Madison Square Garden and drew a then record 1.5 million viewers. He’s hoping to unionize fighters across combat sports. He’s engaged Dana White over UFC fighter pay. Recently, Paul partnered with the Professional Fighters League (PFL), a small MMA outfit, creating a new fighter-friendly pay-per-view model. PFL’s first significant signing: Francis Ngannou, the former UFC heavyweight champ.

In a few short years, Paul has turned himself into a formidable presence in combat sports. But that world is complicated. Messy. A celebrity like Paul, with so many outside interests, may not have the stomach for it. “A guy like Jake, his attention span is so limited,” says Hearn. “If you want to succeed in boxing, it’s a hundred percent all your focus and time to be at the top end, like anything. And he can’t do that because his mind is just everywhere.”

Informed of Hearn’s comments, Paul smirks. “Eddie Hearn is not the person to ever judge Jake Paul. He’s a bipolar Jake Paul fan. One moment he’s like, ‘Yeah, this is amazing.’ The next moment he’s like, ‘F--- this kid.’ Paul pauses. “He’ll see. I’m here to stay.”

Logan Paul loves his brother, a statement that sounds wholly unnecessary—until you hear what comes next. “Growing up, on paper, Jake was a failure,” says Logan. “There’s no other way to put it. Jake was an on-paper failure.” As teenagers growing up Westlake, Ohio, the Pauls dabbled in social media, first with the now defunct Vine, then YouTube. For Logan, it was a means to an end. “Social media for me has always been a stepping stone to become one of the biggest entertainers in the world,” says Logan. And Jake? “Truthfully,” says Logan, “I don’t know what Jake’s intention was.”

Money, Paul says. In the early 2010s, when Paul’s Vine following stretched into six figures, representatives from Doodle Jump, a kid-friendly platforming game, contacted Paul about promoting it, offering $200 for a six-second Vine. “I was like, ‘What the f---?’ says Paul. “I was stoked to get the $200. I was like, ‘This is insane.’ Because I was used to landscaping for $20 an hour or snow plowing for $20 an hour, cleaning gutters. All I had to do was post a Vine for $200?” When Doodle Jump’s downloads soared, the company asked for another. Paul figured he’d go big. He asked for $10,000. “They were like, ‘Yep, no problem,’ ” says Paul.

Boxing started as a similar cash grab. “My purpose at the beginning was to make a bunch of money and f---ing buy a Lamborghini and have watches and s---,” he says. Paul’s pay-per-views (he’s headlined four of them) have, to varying degrees, been successful. Forbes estimated Paul raked in $40 million for three fights in 2021. Paul bragged he made $30 million to fight Fury.

Clay Patrick McBride/Sports Illustrated

Quickly, the sport offered something else: purpose. As a teenager, Paul cycled through the usual, starry-eyed career plans. He wanted to open an auto-body shop. After a couple of years of high school football, Paul dreamed of the NFL. For a bit, he talked about becoming a Navy SEAL. When the YouTubing took off, Logan moved to Los Angeles. Jake went, too. He landed a gig on Disney Channel’s Bizaardvark and founded Team 10, an entertainment collective, and moved everyone into an $18,000 per month mansion in a tony neighborhood outside L.A.

It was lucrative. But, ultimately, unfulfilling. The days got repetitive: Wake up, make a video. “I made one every day for more than 800 days,” says Paul. There were phone calls. Business meetings. Maybe an audition. By 8 p.m., everyone in the house was drinking. That’s when the trouble started. Police were routinely called over noise complaints. In 2017, Paul was fired from Bizaardvark after a local TV station reported on Paul’s neighbors considering a public nuisance lawsuit. In ’18, an ex-girlfriend accused Paul of mental and emotional abuse, and in ’21 two other women accused him of sexual assault. (Of the first allegation, Paul said in 2018, “We did a lot of messed-up things to hurt each other.” He has denied the second allegation, and a representative told Sports Illustrated he had no comment on the third.) In ’20, the FBI raided Paul’s house looking for evidence from a looting incident in Arizona. (No federal charges were brought.)

Says Paul now, “I was really reckless. I didn’t care about my life. I didn’t care about anything that I was doing, really. I was not in a good place. I was lost and chasing all the wrong things to try to find myself.” Asked about regrets, Paul winces. “There was a lot of fake s--- I did for videos that I don’t like, that I did for attention,” says Paul. “Like getting fake-married. I literally got fake-married for f---ing attention.”

Boxing gave Paul direction. In 2020, he moved BJ Flores, a former cruiserweight contender who helped Paul train for his fight with AnEsonGib, in with him. When the pandemic hit, Flores and Paul ramped up the training. His YouTube output slowed. His sparring picked up. “When an individual finds their purpose, they become the best version of themselves,” says Logan. “Boxing for him is that purpose. Jake devoted his body and mind to it. And he’s become a really great version of himself.”

It could have ended there. Rich kid uses influence to penetrate a barrierless sport is an interesting story but hardly original, particularly today, when influencer boxing is its own cottage industry. Paul wanted more. In boxing, Paul saw a decaying sport badly in need of innovation. “The same feeling I had when I started vlogging was the same feeling I had when I started boxing,” says Paul. “Everyone was doing the same s---, and it just wasn’t popping. It’s just this old, outdated s--- that no one’s changed.”

Promotion, Paul says, is a big part of it. “Make people interested in the why,” he says. “People care about stories. Bigger headlines. More articles. It’s all a numbers game. It’s all a clicks game at the end of the day.”

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

Sharing that influence, Paul says, came naturally. “With Team 10, I would sign influencers underneath me and help them get famous,” he says. “So I was like, ‘I could literally do the same thing in boxing.’ ” Women’s boxing intrigued him. Paul grew up a fan of Ronda Rousey, who for several years was one of the biggest names in UFC. Showtime Sports president Stephen Espinoza suggested Paul look at Serrano, a champion with little profile. Paul added her to his undercard for his first fight against Woodley. Paid her six figures. Two fights later Serrano made seven figures against Taylor.

Lou DiBella, a longtime fighter rep who promoted Serrano for several years, admits, somewhat begrudgingly, Paul has become a force. “No network was willing to do with Amanda what he was willing to do,” DiBella says. “No matter how much I wanted to help her, I couldn’t help her like that.” DiBella, incidentally, represents Heather Hardy, who will earn her first six-figure payday when she challenges Serrano on the Paul-Diaz undercard.

There are others. Montana Love turned a knockout win on a Paul undercard into a multi-fight deal with Hearn. Shadasia Green, a 168-pound contender, has seen her profile spike since signing with MVP. Lightweight Ashton Sylve, 19, is Paul’s first attempt to develop a prospect. Social media, Paul believes, is the bridge between success and stardom. “What’s crazy about it is it seems so simple,” he says. “It’s just post and tell the story and create content together. But a lot of people just don’t know how to do that in an organic, authentic way. I think that’s the secret sauce. Why doesn’t everybody do that? I guess it’s not that easy. I don’t know.”

Clay Patrick McBride/Sports Illustrated

Should we get a Ferrari?”

It’s mid-May, and Paul is stretched out on a bed in a villa inside the Ritz-Carlton resort in Dorado, Puerto Rico. A photographer, Clay Patrick McBride, leans against a wall across the room. Paul came prepared for this shoot. He studied McBride’s work. With Kobe Bryant. Jay-Z. Arturo Gatti. “This has got to be a step down,” says Paul.

McBride, perhaps half-jokingly, suggests they photograph Paul in a Ferrari. Paul scrolls through his contacts. He dials, putting the phone on speaker. A man whom Paul identifies as the largest car dealer in Puerto Rico picks up. Paul explains the situation. He asks whether a Ferrari is available. The dealer invites Paul to the lot, where a rare model, one of three ever made, at least according to him, would be waiting.

It’s moments like this that make you wonder whether Paul really is long for boxing. His portfolio is wide. He has Betr and a twice-monthly sports YouTube talk show. Recently, Mandalay Pictures, the company behind Air, announced a deal for Paul to star in a feature film. Needling White over fighter pay makes for good content. Effecting real change is a commitment. “My man could be a monk in the mountains of China in 10 years,” says Logan. “I have no idea what Jake Paul will be doing.”

Asked again whether he has the patience for what’s ahead, Paul shrugs. He points to the progress he has made with his union, formally titled the United Fighters Association. He says he has spoken to a handful of notable fighters who have expressed interest in joining. Anderson Silva, whom Paul defeated in a boxing match last year, is on board. He says he has commitments from five others, too. “The biggest challenge is all the fighters are really difficult to work with,” says Paul. “They’re very selfish. They think it’s too good to be true. A lot of the UFC fighters are scared to go against the regime. They think that if their name’s attached to something, that they’re going to get cut or shelved or lose all their money.

“There’s a ton of interest from boxers. The problem is that you have to start by going up against a corporation. That’s what a union is, going up against a specific entity. In boxing there’s less of that; it’s more scattered. The way to make the dominoes fall is starting with MMA and going against, basically, the UFC. That power and control would trickle into the rest of the combat sports, because the UFC would have to play by a certain set of rules. Then we would bring that over to boxing.”

For now, Paul says, he wants to lead by example. He wants fighters to have more freedom, pointing to how his pay-per-views have been distributed by Showtime, ESPN and DAZN. “These fighters get stuck,” he says. When they reach a certain level, Paul says, they should use that influence—there’s that word again—to boost the next generation, as he has with Serrano. “Floyd’s doing it now with Gervonta,” says Paul. “But imagine if Gervonta was the co-main event during the height of Floyd’s career? Even Gervonta right now, I know he has his company, but he should have a fighter underneath him while he’s becoming the biggest star in the sport.”

There’s a frustration in Paul’s voice. His passion for boxing is real. So too is his desire to grow it, or at least that’s how it feels. Before the press conference, Paul catches himself staring up at a jumbotron with his image on the screen. Years earlier, he had traveled to Dallas for a meet-and-greet. Around 500 fans showed up that day. More than 18,000 are expected to pack the building for his fight with Diaz. “I love the sport,” says Paul. “It’s changed my life. It saved my life. And it can be so much better.”

Moments later, an official waves Paul over to the dais.

“O.K.,” says Paul. “Now let’s go f--- this guy up.”