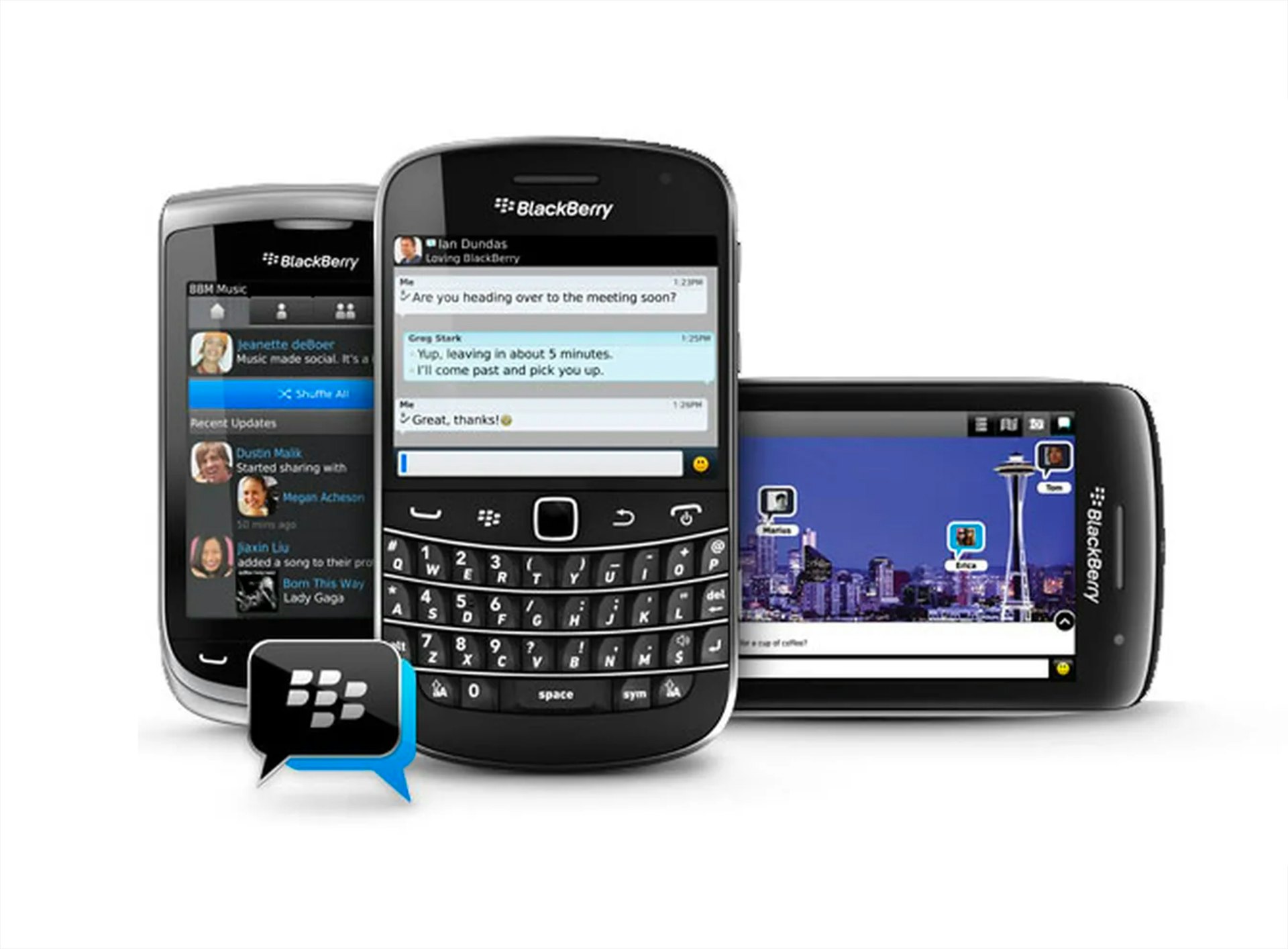

When you think back on the old BlackBerry smartphones, most people probably think about one of two things: the keyboard and mobile email. And although those were endemic to the early success of the first breakout smartphone OS in a pre-iPhone world, the enduring legacy of BlackBerry is something else entirely: it is instant mobile messaging. It is BBM.

Before iMessage, WhatsApp, LINE, Signal, Telegram, Facebook Messenger, WeChat, or whatever mobile messaging strategy Google has decided on this week, there was BlackBerry Messenger. BlackBerry Messenger, better known as BBM to its millions of once-devoted fans, was arguably the original "killer app" of the smartphone age and it set the standard for the way we have communicated via text on our phones for nearly 20 years and defined the blueprint for mobile messaging services as we know them.

First launched by Research in Motion (the company better known as RIM, which would rename itself BlackBerry in 2013) in 2005, the private messaging service had 4 million users in 2008. By 2011, that number had climbed to over 60 million. The brilliance of BBM was that it combined two existing quick messaging paradigms, instant messengers a la AIM and Yahoo Messenger and SMS. But unlike SMS, which U.S. wireless carriers were charging between five and ten cents a message for, BBM was free, included within the data plan that every BlackBerry user paid for either through their carrier or through an enterprise server agreement with their employer. Whereas a normal wireless user might send a few hundred SMS messages in a month, depending on their wireless plans allowance, BlackBerry users would frequently send and receive hundreds of messages a day.

With BBM, you could talk to individuals one-on-one or in groups. In an era before every cell phone supported MMS messages, you could exchange pictures and files. And then there were notifications. BBM pioneered a way to let users know that their messages were both delivered and read via text designations “D” and “R” next to a message. This feature, which was originally created to show users the network was working soon left millions of people in fear of being “left on read.” No longer could a boyfriend or girlfriend pretend they didn’t see an “R U up” message; read receipts told all.

Beyond just “D” and “R” designations, every BlackBerry had a blinking red light that indicated a new BBM message (or email) had arrived to your phone, putting the “crack” in “Crackberry.” Before BBM, the idea of being "always on" was a concept that was reserved for only the most hardcore of computer users; those constantly tethered to a desktop or laptop. After BBM, it was a way of life.

An Unplanned Success

In the new film BlackBerry, we get a glimpse into how BBM was developed. The book, Losing the Signal by Jacquie McNish and Sean Silcoff (itself the basis of the film) goes into more detail:

BBM was the brainchild of a trio of young RIM employees who were looking for something to do following a rare slowdown in 2003 when the company had to lay off 10% of staff. Strategic alliances manager Chris Wormald and programmers Gary Klassen and Craig Dunk, along with two co-op students, explored how to adapt popular instant messaging services such as Yahoo Messenger for BlackBerry. These services enabled users to have real-time text “chats” at their desktop computers over the Internet, typed into a small box in the corner of their browsers.

Not everyone at RIM was convinced that BBM was an endeavor worth pursuing. Instead, it started as a skunkworks project, with much of the work being done in off-hours, after other work was already finished. But everyone who touched BBM knew it was a winner. According to Losing the Signal, the real test was to get BBM adopted by RIM executives. When the assistant of Mike Lazaridis, one of RIM’s then co-CEOs became enamored with the platform, BBM was soon used by almost everyone at the company.

Wireless carriers were hesitant to adopt the service as well. After all, BBM was a competitor to SMS, a huge cash cow that was almost complete profit to the likes of AT&T and Verizon and others. But as RIM made its big push into the consumer space in mid 2006, carriers acquiesced. After all, BBM was the sort of feature that could convince a customer to buy a more expensive phone and tack on a $20–$40/month data plan. That was enough to offset the fears over lost revenue for SMS.

The early brilliance of BBM was that it only worked with other BlackBerry devices. That meant that if you wanted to take advantage of this free rich messaging service, you had to have a BlackBerry device. That exclusivity would eventually become BBM’s downfall, but in the early years, it was a sign of exclusivity and helped pave the way for in-group dynamics. Proto-blue bubbles if you will. Moreover, because BBM worked by making voiceless data calls across RIM’s network of servers, you could send messages to users all over the world. In a time when international SMS and voice phone calls were still prohibitively expensive, this was a breakthrough for those who traveled internationally or those with family members scattered across the globe.

Instead of using a phone number or username/email as your unique identifier, BlackBerry users were issued a unique eight-digit alphanumeric PIN instead. Each PIN was unique to its physical device, which made the process of switching devices sometimes fraught and necessitated the need for PIN exchanges, and for some users of a certain age, your PIN was your identity. Losing the Signal cites cases of women in Dubai embroidering their PIN numbers inside the flaps of their burqas as a way of giving hints to their would-be paramours to “BBM them.” Much as businesses and brands would later join platforms like WhatsApp or WeChat or LINE, plenty of restaurants and local shops would advertise their BBM PIN the same way one might advertise a phone number or URL.

In an era when social networks were still nascent, BBM became one of sorts too, with people meeting strangers in group chats or via BlackBerry or BBM enthusiast forums and becoming friends, or even more. I know at least two married couples who first met via BBM. Jared DiPane, managing editor of commerce at Cnet, shared with me that he met his wife on the CrackBerry forums, when she sought help after a beta version of BBM caused problems on her corporate device. As DiPane says, “then we talked forever, met in person and the rest is history.”

Enter the Competition

If BBM sounds a lot like iMessage or WhatsApp, that’s because those services were modeled in part after BBM. WhatsApp, which was first released to the iOS App Store in November 2009, was clearly influenced by BBM, down to its status and message read visibility. First launched on the iPhone, WhatsApp came to BlackBerry in early 2010, with ports to Symbian and Android following soon after. WhatsApp took what made BBM so compelling but it did it in a cross-platform way. WhatsApp also made the decision to adopt a user’s phone number as their PIN, making the experience even more similar to standard text messaging.

And it wasn’t alone. RIM faced competition from others as well. One service, Kik Messenger, which launched in 2010, was created by former BBM interns who had grown frustrated with RIM’s refusal to take the service crossplatform. RIM promptly sued KIK over patent infringement and kicked it out of the BlackBerry World app store, but the writing was on the wall. People wanted a BBM-like experience but didn’t want to have to own a BlackBerry to get it.

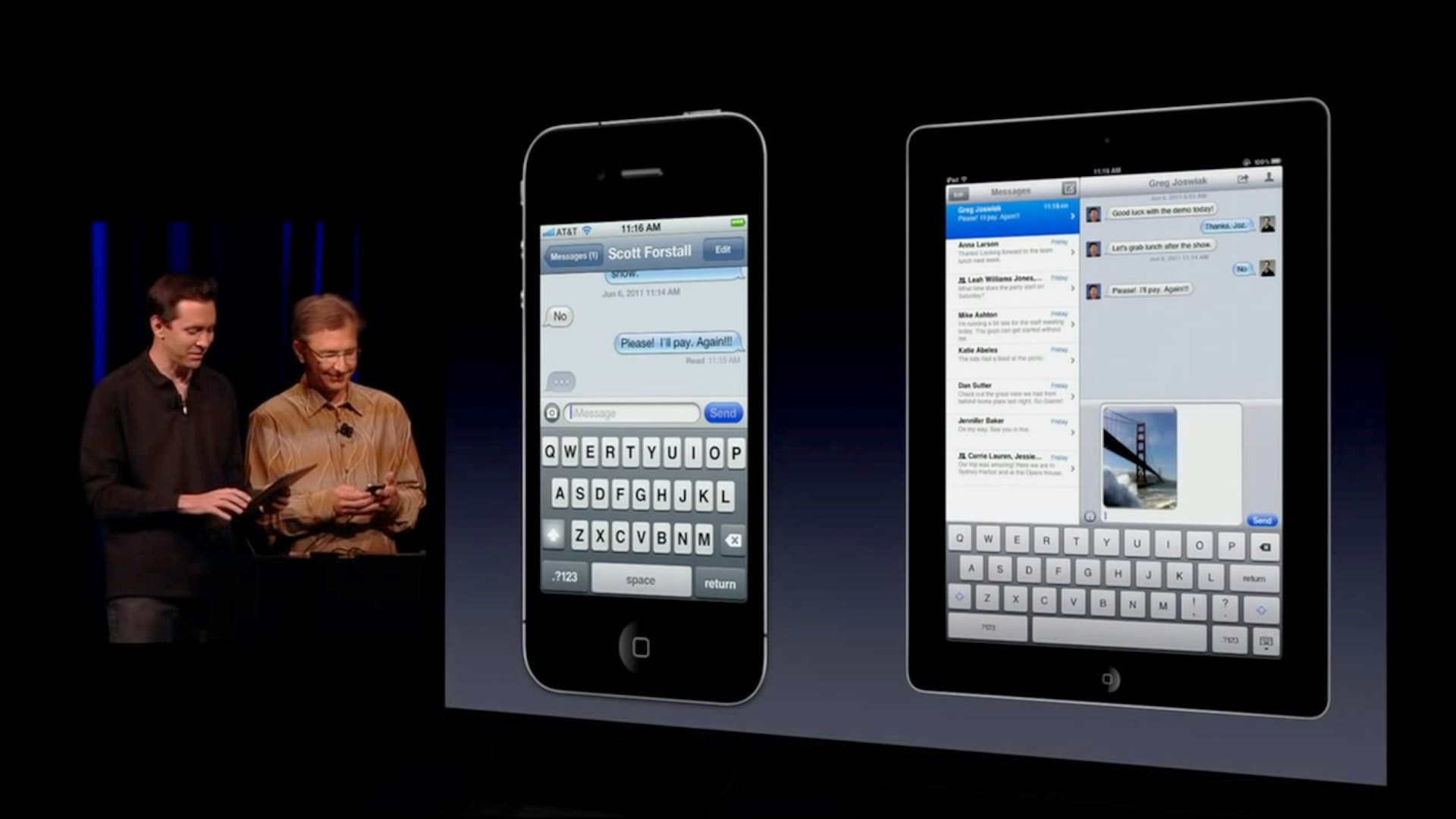

In October 2011, Apple released iMessage, its Apple-only messaging ecosystem. iMessage took many cues from BBM — platform exclusivity, data network reliance, and support for transferring files and photos — but it was also the default messaging app on the iPhone. And a failed iMessage could send as a fallback SMS if you had it configured to use your phone number. And because iMessage worked on all Apple devices — including the iPad and the Mac — that "exclusivity moat" was much harder for people to leave. Plus, by 2011, the iPhone had cemented itself as one of the most important devices in tech history and was continuing to innovate.

RIM co-CEO Jim Balsillie reportedly tried to convince RIM to make BBM cross-platform and available to wireless carriers as a sort of SMS 2.0 (an idea that is very similar to the Google-led RCS system), but that plan failed. Balsillie resigned from RIM in January 2012.

BlackBerry did eventually make BBM cross-platform in 2013 but by then, it was too late. Although BBM still had tens of millions of users, competing platforms had many, many more. By the time WhatsApp was sold to Facebook for more than $20 billion in 2014, it had over 450 million users. Today that figure is more than 2 billion.

A Lasting Legacy

BlackBerry (as the corporation is now named) eventually licensed the consumer version of BBM to Emtek, an Indonesian mobile application company in 2016. By 2019, even Emtek had given up the ghost, shutting down the consumer service for good.

By 2013, there was nothing left on BBM that you couldn’t find in half a dozen other services, but even a decade later, every text-based messaging app we use was still crafted using the mold that BBM delivered.

Eighteen years ago, the idea that users would primarily communicate using text and data — not voice — on their phones would have seemed absurd. After all, the purpose of a phone was to have voice calls. If you’re anything like me, you talk to dozens of people a day via text but most of the voice calls to your phone are from spammers. I only call people after they haven’t responded to multiple iMessage messages.

That’s the impact of BBM. BlackBerry might always be associated with a keyboard, but it is always-on mobile messaging — making all of us available instantly anywhere in the world, as we hang on to see that next reply or reaction — that will forever be its legacy.