When Justin Holcomb described the future for humans on the Moon, the Kansas Geological Survey postdoctoral researcher began with a commonplace answer about the rapid pace of human progress.

"The first crewed airplane with an engine that actually flew occurred in 1905," Holcomb said, referring to the Wright Brother’s Flyer. "A little over 60 years later we were walking on the moon. Where will we be in another 60 years?"

While this may have sounded like an invitation to wax poetic about the wonders of human space exploration, Holcomb's enthusiastic summary of space races (old and new alike) soon took a more prosaic turn. Holcomb is also preoccupied with the physical legacy left by humans on the Moon — intentionally and otherwise.

This is the central idea behind the concept of the "lunar Anthropocene," or the theory that the geologic history of the Moon has entered a new phase because of human interference. On Earth, we divide different geologic eras into epochs. The oldest is the Hadean, which marks the period in which our planet first formed some 4.5 billion years ago, around the same time our moon formed as well.

Together, our homeworld and our largest satellite have gone through many dramatic changes over the centuries, from volcanic eruptions to powerful meteor impacts. Earth is currently in an epoch known as the Holocene, but some scientists argue that the Industrial Revolution is so impactful, we have shifted into an entirely new era: the Anthropocene, from the Greek word for human. The term was popularized more than two decades ago by atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer, an ecologist and paleolimnologist.

Not every geologist agrees with this assessment — some argue our impact will be minimal in the geologic long-term, though devastating for us and most other species in the short-term. Nonetheless, while it's not an official term, the concept of the Anthropocene helps illustrate how humans have changed Earth through climate change, plastic pollution, light pollution, biodiversity loss and in many other ways.

The question is, if we live in the Anthropocene, does the same concept apply to the Moon? That's precisely the argument a group of anthropologists and geologists propose in a recent commentary in the journal Nature Geoscience. If accurate, Holcomb and his co-authors Rolfe David Mandel and Karl William Wegmann believe the lunar Anthropocene began thanks to the Space Race of the mid-twentieth century.

"The lunar surface preserves two distinct periods of human activity, including the space race of the mid-twentieth century and our

more recent robotic lunar exploration," the authors write. The first phase includes the Cold War era, during which the United States and Soviet Union competed for military dominance through a proxy war of scientific progress in outer space. A newer phase of the space race, which commenced with the onset of the 21st century, is fueled by the private sector as well as government endeavors.

"Since 2001, private companies acting semi-independently from government agencies have funded and promoted novel and relatively affordable access to space," the authors explain. "Their activities include the development of space tourism, investments in lunar surface habitation and mining, research and development in space manufacturing and assembly, new cislunar orbits and satellite internet constellations."

To understand the consequences of all this activity, it is first necessary to break up the Moon's history into its official phases. Much as the Earth's history has been shaped by geology and climate, the Moon has a geologic timescale based on lava infilling and impact craters. Its five time periods include the Pre-Nectarian, Nectarian, Imbrian, Eratosthenian and Copernican. The last of those, the Copernican, covers the last 1.1 billion years of history — long before mammals, let alone human beings, even existed.

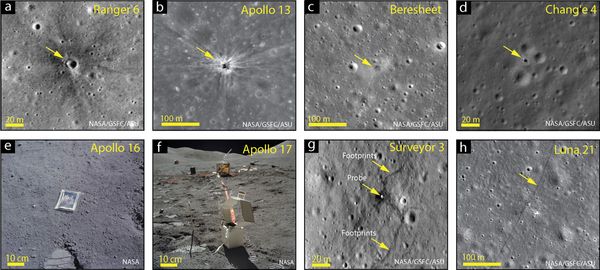

So what kinds of materials could be left behind by human activity, and to such an extent as to break the Moon out of the Copernican period? The list is quite various and includes, as Holcomb and his co-authors put it, "discarded and abandoned spacecraft components, bags of human excreta, scientific equipment, and other objects (e.g., flags, golf balls, photographs, religious texts)." The authors add that "footprints and rover wheel tracks are extensions of the human presence on the Moon and should be considered important cultural features of our species’ dispersal across our solar system."

These pollution concerns do not even begin to cover the issues that arise with spacecraft debris. According to the U.S. Space Surveillance Network, there are more than 36,500 pieces of orbital debris at least 10 cm in diameter or larger, and "only minimal effort is being made to track the deposition of space heritage on the Moon and elsewhere."

Writing to Salon, Holcomb cited historical archaeologist Pete Capelotti when the latter identified five categories of lunar artifacts: "lunar module ascent stages, lunar module descent stages, Saturn V third-stage rockets, subsatellite science probes, and lunar rovers."

"Each of these categories would have further artifacts," Holcomb added, "but especially scientific equipment."

There are several problems with leaving behind all of this stuff, as well as with the human activity which causes it. One is that some of the scientific and other materials left behind by humans retain historic significance. No one wants the sites of Apollo 11 or Chandrayaan-3 (India's impending Moon mission) to be lost forever. Additionally, as the authors write, "we know that while the Moon does not have an atmosphere or magnetosphere, it does have a delicate exosphere composed of dust and gas, as well as ice inside permanently shadowed areas, and both are susceptible to exhaust gas propagation." They urge future missions "must consider mitigating deleterious effects on lunar environments."

This naturally raises questions about whether the private or public sector is best equipped to handle lunar exploration going forward. On this, Holcomb takes a nuanced view.

"I think that it’s a good thing that the New Space Race involves more than just government entities, because it allows more diversity in the space industry, which means more unique problem solving and innovation," Holcomb said, emphasizing that he is against neither space exploration nor humans returning to the Moon. "One downside, however, to the privatization of space exploration is that literally anyone could land on the moon and disturb various areas. We do need to ensure legislative oversight as we move into this new space future, and this should be an international endeavor."

He added that although the 2020 Artemis Accords lay out a foundation for law on the Moon, they are non-binding "and only has one line dedicated to space heritage. Regardless, it is a step forward and we should begin ensuring efforts like this are at the forefront before the colonization of the moon begins."

When asked if there were any other important points he felt needed to be broached, Holcomb returned to the subject of preparing for humanity's inevitable colonization of the Moon — and the role that archaeologists can play in preparing our species.

"The return to the moon has begun, and I believe we will be across the transition by 2050," Holcomb explained. "Our goal with this paper is to initiate discussions about what this means now, rather than later. One way we could discuss this historical point is by placing it in the theoretical context of the Anthropocene (age of humans). In this way, we can place our recent impact on the moon into the history of human evolution as a species and measure it through the archaeological record produced by humans since our exodus out of Africa."

This is why, Holcomb concluded, a robust conversation must occur including multiple fields not normally associated with planetary science including "anthropology, ecology, and of course, archaeology."