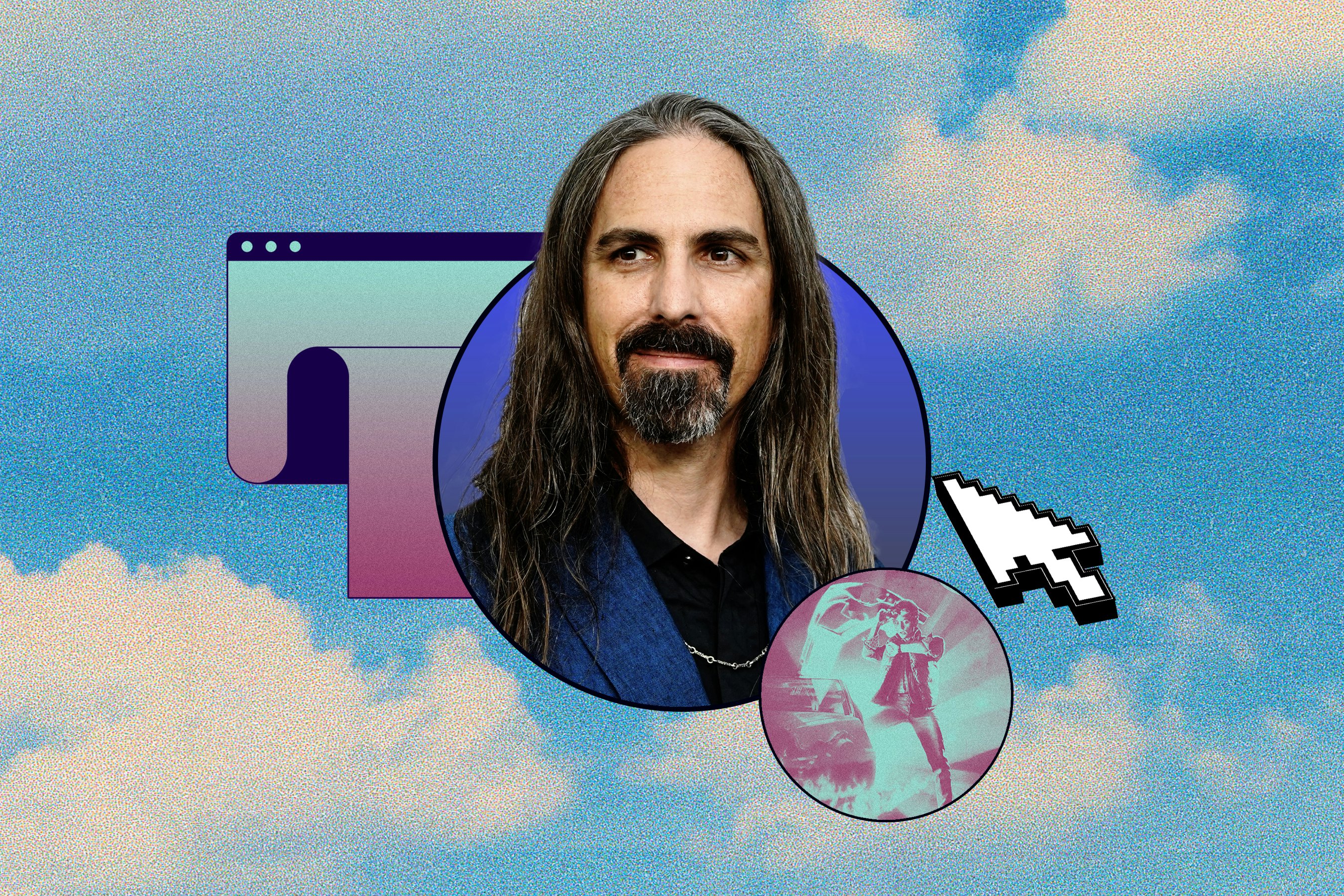

While most kids in the ‘90s made mixtapes full of Michael Jackson and Metallica, Bear McCreary was vibing out to illegally recorded movie scores.

“For me, it was always like, big action cues and epic fanfares,” the film and TV composer tells Inverse, recalling the contents of mixtapes that contained everything Bernard Herrmann’s work for The Day the Earth Stood Still to the main titles of Batman and Conan the Barbarian. A young McCreary relished long road trips where he could escape the real world with headphones on. “I would love nothing more than to stare out the window and listen to film music.”

As an adult, McCreary pays homage to his influences as one of Hollywood’s pre-eminent genre film and TV composers. Even if you don’t realize it, you’ve heard his music in everything from Battlestar Galactica to The Walking Dead to Godzilla: King of the Monsters to blockbuster video games like Call of Duty: Vanguard and the God of Wár series. But his most ambitious work to date is Amazon’s The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power.

McCreary’s lifelong passion began with Back to the Future. He cites Alan Silvestri’s “brassy, adventurous tone” for stirring something in him. “I made my mom bring me back the next night and I had a little Fisher Price recorder,” he says. “I held it over my head to record the movie. Every time my mom laughed, because it was a funny movie, I scowled at her. She was getting on my audio!”

A few weeks later on an errand to the local pharmacy, McCreary saw something otherworldly: A cassette tape section that sported the logos of movies like Star Wars, Beetlejuice, and of course, Back to the Future. “I went, ‘Wait, what? You can buy a cassette of the music without the dialogue?’ That was it. That was the beginning of the end for me.”

Check out our conversation with Bear McCreary about his obsession with sci-fi and fantasy film scores below.

Geeking Out is an Inverse series in which celebrities tell us about their nerdy and niche interests, hobbies, or collections.

What is it about film scores that you love?

I was an outlier in my social group. We would go see some sci-fi movie, and I would say, “Did you hear what Jerry Goldsmith did?” There’s something about film music in general that allows me to go to other places in my imagination.

What was on your mixtapes?

The main title from Conan the Barbarian by Basil Poledouris. The main title from Batman Returns. Ennio Morricone from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Bernard Herrmann’s Journey to the Center of the Earth, The Day the Earth Stood Still. Willow and The Rocketeer from James Horner. Jerry Goldsmith’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture. Indiana Jones, of course. “March of the Slave Children.”

It was often secondary themes and cues that I would listen to more than the main title. There were cues that pulled me into these fantasy worlds that were exciting.

What are the hallmarks of a great fantasy film score? What do your influences like Bernard Herrmann, John Williams, and Danny Elfman have in common?

Melody, first of all. There are scores that don’t use melody that are effective, or use melody in a restrictive way. John Carpenter did this effectively in Halloween and other scores. Melody that gets hooked into your mind. Also, a sense of narrative adventure. You feel like you are going somewhere. When I close my eyes and listen, I imagine stories. That’s what separates film music from pop and rock ‘n’ roll, which inherently stays in its lane. It’s telling you something specific. Film music ebbs and flows.

They had a voice that was identifiable in their music. Even when I was a kid, I’d be in the theater or we would rent the VHS, and I would turn to my mom and say, “Danny Elman wrote the music.” A minute later in the main title, it would say “Music by Danny Elfman.” She looked at me like I'm psychic. She had no idea how I was doing this.

Describe how exactly you feel transported by film music.

I don’t necessarily feel like I am in the movie. I don’t get pulled into Star Trek. I don’t go to Mordor. I don’t go to the Temple of Doom. Even as a kid, I was able to separate them. Most people who listen to film music, if they have feelings about it, it’s associated with where it came from. I’m a weird outlier in that.

What’s an example of a movie that’s eclipsed by its music?

Conan the Barbarian’s a great example. I love that movie, but to be clear, the music is better than the movie. The movie’s great. The music is transcendent.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture, same deal. “Ilia’s Theme,” which Goldsmith wrote as a sort of secondary love theme, is one of the most beautiful pieces of music in the history of film. I get chills just thinking about it. But is Ilia one of the most interesting characters in the history of film? Not even close.

In 1998, producer Robert Townson said: "I would cite The 7th Voyage of Sinbad as one of the scores which most validates film music as an art form and a forum where a great composer can write a great piece of music." Do you agree? What makes Bernard Herrmann's work enduring?

That is one of the quintessential fantasy film scores. If not the one. It had this swagger that was really awesome and compelling. It was one of these early films that separated what I’m going to lovingly call a “generic orchestral bombast.” It had this Middle Eastern feel. The way it modulates and just keeps going is not a Western philosophy.

Bernard Herrmann, in a way, is the godfather of all genre scoring. It goes back to Citizen Kane, which isn’t a genre film, but it’s a genre score. Herrmann was emerging onto the scene when traditional symphonic orchestra was the color palette. He didn’t subscribe to that. That’s why his sounds are so iconic. Beginning with Citizen Kane, he was chipping away at that sound. With 7th Voyage to Journey to the Center of the Earth, he’s throwing out the rulebook. I didn’t even mention his work with Alfred Hitchcock, Vertigo, and Psycho. That’s how good this guy is.

Jerry Goldsmith on Planet of the Apes saw what Bernard Herrmann was doing and was like, “I will raise you,” and he made the most weird, alien-sounding score. Even when you listen to it now, the main title of that is off-putting. But that’s where he was taking you. He was taking you to the Planet of the Apes. These composers were among the first to look at the form of music and say, “Why don’t we step away from traditional sounds?” Fantasy worlds require fantasy colors. That had a profound impact on genre musical storytelling.

You’ve cited John Williams as a big influence. What did John Williams do on Star Wars that made that work so iconic?

There’s this thing called the 30-year nostalgia window. Artists look back to their childhood to make art. George Lucas made Star Wars, which was essentially the pulp stories of the ‘40s. So what John Williams did was buck the trend, which was the Jerry Goldsmith experimental scores of the ‘70s. In the auteur period of the ‘70s, people were not doing big, orchestral sounds. The Godfather is orchestral but it’s intimate. Well, John Williams had fond memories of that. He, like Lucas, reinvented what he loved. He did the “A-plus” version of an outdated idea. People weren’t scoring science fiction with that kind of color, and he did it skillfully and memorably. He did it boldly. To hear that kind of big symphonic sound, it had been a couple decades of film not doing that. Star Wars starts with a full orchestra on that logo, the trumpets on high. We all know that sound, but it was bold.

He ironically defined science fiction for a few decades to the point that when I did Battlestar Galactica, to not use orchestra but use taiko drums and Middle Eastern instruments, that was weird. Now that's not weird. Bucking the trend and trying something different is how you make something memorable.

So it’s about recapturing the spirit of a style rather than actually replicating it?

Absolutely. I’ve done this myself. I’ve seen the Peter Jackson trilogies dozens of times. When I got hired on The Rings of Power, I did not go back and watch them. I didn’t need to, they were ingrained in my DNA. I thought, “I wanna make a score that makes you feel the way how Howard Shore made me feel.”

I did Netflix’s Masters of the Universe: Revelation, which is a He-Man cartoon that’s completely straightforward. Does my score sound like the old He-Man cartoon? Not one iota. But it tells you how I felt when I was 4 years old watching He-Man.

Is there anything about the modern era that concerns you?

To a degree, big-budget filmmaking has a more homogenous sound. Movies have been less experimental over the last 15 years. The trend has gone from desiring a score that’s bold to one that isn’t. The ripple effect of that has been that, oddly, the art form I grew up loving did get sort of sidetracked for a while.

It doesn't worry me because people of my generation that grew up remembering Star Wars and Indiana Jones are now doing scores like Rings of Power or a game score like God of Wár — huge and unembarrassed to be orchestral.

One last question: Can you break down the track “Galadriel” from The Rings of Power for us?

Galadriel’s theme was tricky because she is a conflicted hero. She’s driven by an obsession with finding Sauron. She’s driven by sadness that is observed but downplayed in the first season. You see it in Episode 7 when she just kind of mentions Celeborn and you’re like, “What?” There’s this whole life we don’t know about, and you realize she’s holding all this sadness in her. There must be some sadness in her theme, but ultimately heroism.

It goes back to my favorite thing: melody. I needed a melody that had a hook right at the beginning. Those first three notes, that minor seventh leap up. It is the only theme that has that particular leap. I designed all the themes in the show, so the first two notes are unique. It’s designed to be memorable.

It was one of the bigger challenges because there’s so many layers to her. I’m planning for the future: The Galadriel we see in the books and the Peter Jackson films is someone who’s clearly had some trauma in her past. We’re gonna see more of those layers.