“How are they losing their children like this, all over the country? They aren’t used to the desert.”

These are the thoughts of a Pashtun cameleer in Fiona McFarlane’s second novel, The Sun Walks Down, set in South Australia’s Flinders Ranges in 1883. This “bit part” cameleer is one of the few characters with a first-person address in McFarlane’s polyphonic, multifaceted saga that explores the cultural narrative, anxiety, and stain of white Australian presence on arid Australian land.

Bruce Chatwin, in his seminal novel The Songlines (1987), suggests “Australia […] is the country of lost children”. Indeed, the figure of the lost, innocent white child has pervaded Australian culture since the early 19th century.

Review: The Sun Walks Down – Fiona McFarlane (Allen & Unwin)

I, too, have researched lost children for my own novels set in outback Australia, using the motif of a lost child to reflect wider cultural anxiety.

As Peter Pierce suggests in his The Country of Lost Children (1999), “the idea of losing one’s child to a strange and silent country reflected the depth of white settlers’ distrust of their new land and its Aboriginal inhabitants”. Pierce suggests this deep anxiety can be traced to white settlers arriving “in a place where they might never be at peace”.

In her masterful, complicated novel, McFarlane takes this further – she asks readers to consider a future of continued unsettlement, where white Australians are always chasing “something very precious, that nobody can find”. She suggests the lost child remains a pervasive symbol, highlighting unresolved unrest between white Australia and its tenuous connection to land.

Earlier in the novel, an Aboriginal stockman, Billy – himself uninitiated and not named as belonging to any specified tribe – reflects:

A lost child is the thing white people are most afraid of. It is the one cost of settling on this country that they consider unreasonable.

Perhaps McFarlane is saying that it is also the thing most inevitable.

Read more: The 'lost child' is a white Australian anxiety about innocence

Terror, unbelonging and yearning

While McFarlane’s novel centres around the colonial ur-narrative of being lost in the land, she is really exploring the resulting feelings of terror, unbelonging and yearning.

She asks how it is possible to move forward in a land that first arrived in Anglo-Australian history as “a timely opportunity” and came afterwards “in the manner of a birthright”. She seems to suggest, so far at least, that Anglo-Australia has moved forward by controlling the narrative to its own ends.

The novel opens with an innocent, blonde and blue-eyed Denny, wandering through “desert country” to “collect things for the fire”. It is not long before a “high, dark wall” of a dust storm envelops Denny, his town of Fairly, and the wider South Australian Flinders Ranges.

Over seven days and nights, the story documents the resulting search for Denny, told through the perspectives of a massive cast of characters. Among them are Denny, his parents, his teenage sister Cissy, travelling artists Karl and Bess Rapp, the newlywed policeman and his wife, Indigenous trackers, the local vicar, and newly arrived Sergeant Foster.

Interspersed into these third-person limited perspectives, we are given eight intimate direct addresses: from the cameleer, a Yadliawarda maid, an Irish maid, a German widow, a Ramindjeri tracker, a German prostitute, an Australian writer and an English artist.

Read more: On the frontier: the intriguing dance of history and fiction

Unsettling style

I initially found the jolt between the narrative styles unsettling; perhaps this was McFarlane’s intention. However, the effect is to show many perspectives, each grappling with their own relationship to this arid land – and how tethered, or untethered, they feel towards it.

The first-person perspectives simultaneously allow us a window into voices often omitted from the Australian settler story (like the maids and cameleer), and subtly ask us to consider how stories – and who tells them – can shape a narrative.

This is particularly so when the “Australian writer” and the “English artist” take up the tale, each of them massaging the facts of Denny’s disappearance into heroic fictions of discovery, control, and ingenuity – within and of the land.

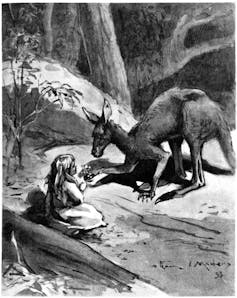

Bess Krupp – or, the “English Artist” – goes on to publish a successful children’s story inspired by Denny’s disappearance. This story seems like a version of Ethel Pedley’s actual 1899 text, Dot and the Kangaroo, exploiting the lost child motif and inverting it so that the desert can be somewhere a person can be reinvented anew (albeit through their own control over land).

We could argue McFarlane is also a white invader controlling a narrative: one of the many “Gods” who, while producing art about this land, “made use of a thing that wasn’t mine”.

As McFarlane explores characters cut off from real and metaphorical mothers, others feeling “both claimed by and exiled from” their new world, and others chasing “something very precious”, she explores the exploitative nature of storytelling and myth-making. She asks us to consider the truth of the tales we tell about ourselves and our identities, questioning whether there may be other lenses through which to view our past and our future.

The novel really comes together in the second half, once the characters begin to meet, interact and influence each other from inside the land. I admit, I did find the first half of the novel on the slow side, reading what felt at times like an endless introduction to more characters within the same patch of land.

However, once we move towards the fiery and thrilling conclusion, the novel’s ideas around belonging, destruction and loss come to the fore. As I reached the final few pages, I could see why Ann Patchett had labelled McFarlane’s story as one she is “always longing to find”. It has all the makings of a seminal, important text.

Lucy Christopher received a small Amount of funding from the Arts Council of England to conduct a research trip to Western Australian deserts in order to write her novel, Release.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.