The story so far: If a man promises to marry a woman but never intends to, and still has ‘consensual’ sex with her, it will amount to a criminal offence under Section 69 of the proposed Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023. The Bill, which seeks to replace the Indian Penal Code, 1860, identifies ‘sexual intercourse on false promise of marriage’ as an offence.

At present, the offence is not carved out separately in the IPC, but courts have previously dealt with similar cases through other provisions within the criminal law framework, with a Bench of the Supreme Court deliberating on a case this week itself.

The BNS is one of three new draft criminal law Bills brought by the Union Government on the last day of the Monsoon Session. A Standing Committee on Home Affairs has three months to review, carry out consultations and submit its report on the Bills.

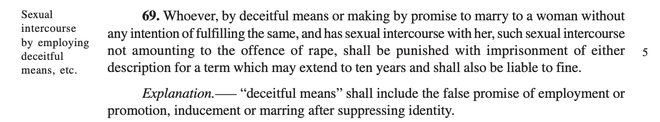

What does Section 69 say?

Chapter 5 of the Bill, titled “Offences against woman and children” describes ‘sexual intercourse by employing deceitful means etc.’, as follows:

Section 69 creates two violations: one by deceitful means, and one by a ‘false promise to marry.’ Deceitful means will include the “false promise of employment or promotion, inducement or marrying after suppressing identity.” The false promise to marry will be attracted only when a man makes a promise to marry a woman, with the intention of breaking it, for the purpose of getting her consent and sexually exploiting her. Both offenses will extract a penalty of up to ten years of imprisonment.

While introducing the Bills, Home Minister Amit Shah said: “Crime against women and many social problems faced by them have been addressed in this Bill. For the first time, intercourse with women under the false promise of marriage, employment, promotion and false identity will amount to a crime.”

How has IPC dealt with cases of ‘false promise to marry’?

In 2016, a quarter of the total rape cases registered in Delhi pertained to sex under “false promise of marriage,” per Delhi Police data. The National Crime Records Bureau in the same year recorded 10,068 similar cases of rape by “known persons on a promise to marry the victim” (the number was 7,655 in 2015).

Researchers Nikita Sonavane and Neetika Vishwanath explained that these cases happen in one of two ways: when rape is committed, and the promise of marriage is used to silence the victim, or where the promise is made to ‘convince’ the person into entering a sexual relationship. In both scenarios, activists note such cases play out mostly among socially disadvantaged women, given that legal remedy cannot be easily sought.

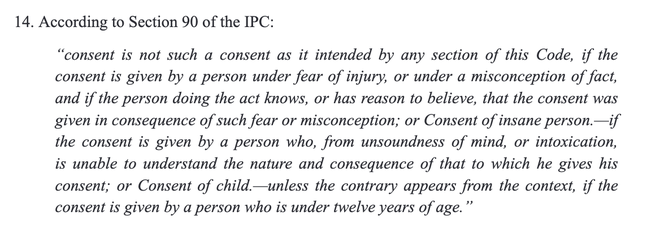

BNS penalises those coercing women into sexual relationships. Previously, these cases were dealt with through a joint reading of Sections 375 and 90 of the IPC. Section 375, which defines rape, further defines consent as “an unequivocal voluntary agreement when the woman by words, gestures or any form of verbal or non-verbal communication, communicates a willingness to participate in the specific sexual act.” Explanation 2 of Section 375 also lists seven types of consent which would amount to rape if violated; these include if a man has sexual intercourse with a woman “without her consent,” or consent taken through fear of death, hurt or intoxication.

In 2021, the Supreme Court reiterated that under Section 375, a woman’s consent “must involve an active and reasoned deliberation towards the proposed act”.

Courts dealing with ‘false promise of marriage’ cases

Section 90 says consent, given under “fear of injury” or “misconception of fact,” cannot be considered as consent. False promises to marry cases are dealt with under the latter, where a ‘misconception’ is used to assess the validity of consent. Legal scholars have questioned the use of Section 90 to interpret consent, given that Section 375 already lays out a definition.

‘False promise of marriage’ vs ‘breach of promise’

The law has distinguished between a ‘false promise’ and a ‘breach’ of promise on the basis of proving if the man intended to marry at the time of engaging in sex. While there is no check-list, cases usually analyse two parameters:

- If the promise was false, with the intention of being broken later on. This would disregard a woman’s consent through a misconception of fact and would be considered rape. (“...where the promise to marry is false, and the intention of the maker at the time was not to abide by it from the beginning itself, but to deceive the woman to convince her to engage in sexual relations,” the Supreme Court noted in ‘Pramod Suryabhan Pawar vs. State of Maharashtra’ in 2019.)

- The false promise itself must be of immediate relevance, or bear a direct nexus to the woman’s decision to engage in the sexual act, as argued in Sonu alias Subhash Kumar vs State of U.P. And Another in 2019.

Courts have previously recognised the ambiguity in determining consent and intention in such cases. The SC observed that a false promise is “given on the understanding by its maker that it will be broken.,” but a breach of promise is “made in good faith but subsequently not fulfilled.”

Put simply, if a man can prove he intended to marry the woman before he entered into a sexual relationship, but later is unable to due to whatever reason, it is not legally punishable. The Supreme Court in 2022 held that consensual sex on a ‘genuine’ promise of marriage does not constitute rape.

“The court, in such cases, must very carefully examine whether the complainant had actually wanted to marry the victim or had mala fide motives and had made a false promise to this effect only to satisfy his lust, as the latter falls within the ambit of cheating or deception,” the Supreme Court said.

The case of Dileep Singh vs State of Bihar

The politics of proving ‘intention’ to marry

False promises of marriage cases look at two central issues: how consent is obtained— through deceitful means, or by misconception? —and whetherthe man ever intended to marry the woman.

The Supreme Court this year said every breach of promise is not rape, noting: “One cannot deny a possibility that the accused might have given a promise with all seriousness to marry her, and subsequently might have encountered certain circumstances unforeseen by him or the circumstances beyond his control, which prevented him.”

But activists argue that ‘circumstances’ are shorthand for social norms that uphold the status quo, reinforcing gender roles, patriarchy and caste lines. Moreover, Section 69 in the BNS codifies the offence instead of creating a new one. Thus, in its present form, the Bill doesn’t dissolve the confused distinction between ‘false promise’ and ‘breach of promise,’ and overlooks the inherent limitations in criminal law which feminist and anti-caste activists have pointed out, lawyer Surbhi Karwa stated in an article.

There are two critiques that may spill over to Section 69, if unscrutinised. One, as scholars like Nivedita Menon have argued, is that such applications promote restrictive ideas about women, marriage and consent; they hinder women’s autonomy and re-victimise them. Courts have previously relied on a woman’s age, sexual history and marital status to question their ability to ‘trust’ the promise of marriage. “If a fully grown-up lady consents to the act of sexual intercourse on a promise to marry and continues to indulge in such activity for long, it is an act of promiscuity on her part and not an act induced by misconception of fact,” the Delhi High Court ruled in a case. Activists note that these train a ‘victim-blaming’ lens on the issue and shift the burden to women to prove their consent was vitiated.

The vagueness, and discretionary nature of rulings, often power the narrative that these are instances of ‘love gone sour.’ In 2017, Justice Pratibha Rani of the Delhi High Court, taking umbrage at the rising number of such cases, implied that women use rape laws as “vendetta”. “...on [a] number of occasions that the number of cases where both persons, out of their own will and choice, develop consensual physical relationship, when the relationship breaks up due to some reason, the women use the law as a weapon for vengeance and personal vendetta.”

Feminist scholars have reiterated, however, that rape law is often the only recourse available to women to seek damages or maintenance. Similarly, in the August 21 case, the Supreme Court Bench of Justices Sanjay Kishan Kaul and Sudhanshu Dhulia remarked on a false pretext of marriage case: “So far as it is consensual and between adults, there is no problem. But when you choose to live by your own standards, you should also be ready to face all the possible consequences.”

Two, the law promotes endogamy and shifts the conversation away from the real harm and abuse that women face, as researcher Nikita Sonavane has pointed out. Ms. Sonavane in a paper looked at ‘false promise on marriage’ rape judgments passed by a district court in Chhattisgarh where the prosecutrixes, belonging to a Scheduled Caste, took recourse under sections 376 and section 90 of IPC. Her findings showed, “...impossibility of an inter-caste marriage was also used as a ground to acquit the accused of rape. The Court is in fact upholding the archaic practice of marrying within one’s own caste.”

The judgment in Uday v. State of Karnataka (2003) became the basis for several future outcomes. A woman from an OBC caste accused a Brahmin man of raping and impregnating her. The man promised to marry her but later reneged on the promise. A Supreme Court Bench ruled against rape, saying there was no evidence to show a lack of intention; instead, since the parties belonged to ‘different castes,’ the victim had to be ‘clearly conscious’ of the ‘stiff opposition’ the relationship would face, and this wasn’t a case of misconception. Ms. Sonavane noted how this “promotes endogamy” and reified “the institution of caste while also penalising the prosecutrix for not adhering to caste norms.”

Ms. Sonavane reimagined a ‘feminist’ interpretation of this judgment, which does not rely on ‘character assassination’ of women, moves outside a binary idea of consent and acknowledges the ‘fraught social context in which women operate...’. Such cases would go beyond criminal law to offer reprieve to women through civil damages.

Without clarity on ‘justifiable intentions’, commentators add the Bill would empower a cycle where the consequences of crime are specified, but the consequences of harm, which women bear, are overlooked.