DiDi Richards lit up when she was asked to identify her favorite non-basketball moment of the 2021 WNBA season.

“Me, off the court, I think would be Napa,” the smiling Liberty guard told the media in late September, though she took issue with the sweetness of the wine, an opinion echoed by the teammate sitting next to her on the podium, Michaela Onyenwere, who immediately nodded at the sound of the word “Napa.” Richards visibly relaxed as she recounted the trip. “Napa was so much fun, though. It was just an opportunity for us to get together as a team and just be beautiful, and you all know I love that. So I was just planning for days what I was going to wear to Napa once they told us.”

After the trip, then Liberty guard Jazmine Jones said the team’s owners “treat us just like they treat the NBA team.”

Or as Sabrina Ionescu asked in her TikTok from the festivities, “Can your owners do this????”

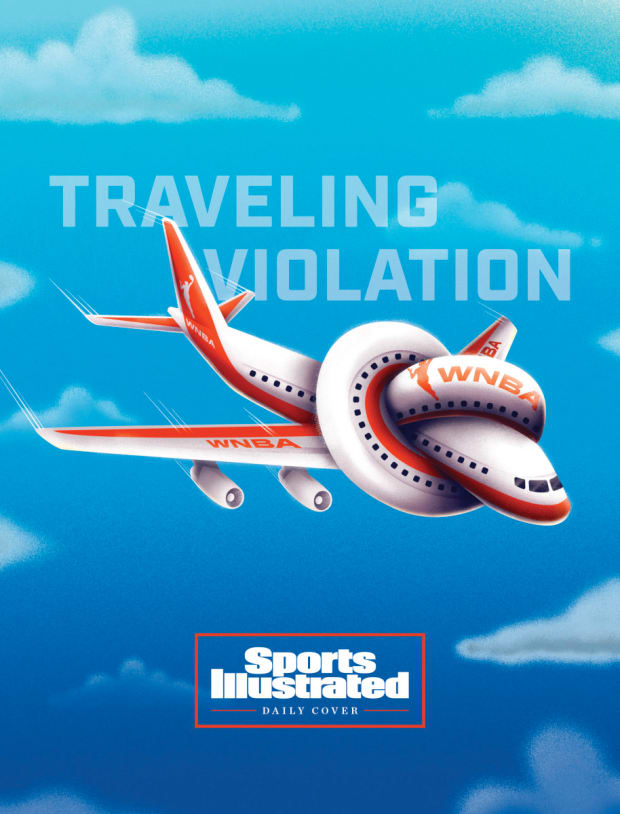

Illustration by Davide Barco

No, WNBA owners cannot. The Napa trip, over Labor Day weekend, violated the WNBA’s collective bargaining agreement, a benefit that vastly exceeded the allowable compensation to players. So, too, did the charter flights Liberty owners Joe and Clara Wu Tsai bought and provided to their team repeatedly throughout the second half of the WNBA season, a competitive advantage for New York that led to a league-record $500,000 fine of the team—originally floated by the league at $1 million, reduced on an appeal, itself an irregular process—and the removal of Liberty executive Oliver Weisberg from the league’s executive committee, sources told Sports Illustrated. The league confirmed these details, as well.

After someone alerted the WNBA to the Liberty’s violations, possible remedies floated by the league’s general counsel, Jamin Dershowitz, ranged from losing “every draft pick you have ever seen” to suspending ownership, even “grounds for termination of the franchise,” according to a Sept. 21, 2021, communication between the league and the Liberty reviewed by SI.

But the issue of charter flights—one that frequently animates the league’s players on social media, and that led to the cancellation of a game in 2018—is simply part of a larger, more complicated tug-of-war taking place among multiple factions of WNBA ownership over the pace of the league’s growth.

A quarter-century into its existence, the WNBA features a mix of aggressive new owners eager to signal their optimism for the future and old-school owners who prefer the conservative approach that defined the league’s past. This is happening within a broader landscape of massive investment across women’s sports, really, for the first time in the U.S.

Born from it is a unique scandal, in which a prominent franchise stands accused of treating its players too well.

Christian Petersen/Getty Images

To understand the challenge facing commissioner Cathy Engelbert and the WNBA, it is necessary to know first the ownership structure of the league. For the first 25 years, the WNBA had been owned 50% by the NBA’s 30 teams, with the other 50% divided among each of the 12 WNBA teams. That has led, not surprisingly, to divergent views of how to maximize those ownership stakes.

For some owners, the WNBA team has been a place to park losses elsewhere in their corporations. Some view it as pure charity—one WNBA owner proudly proclaims the value of the WNBA team to be zero, according to multiple league sources, and thus all he spends on his team is effectively a contribution toward the greater good of women’s sports. And others have invested consistently in their teams, turning about half of them into consistent profit makers.

But it’s all been done on a small scale, because to make significant changes to the status quo requires the buy-in of not only the WNBA Board of Governors, but also the NBA Board of Governors, many of whom see the profit or loss of the WNBA as a rounding error.

The July 2019 hiring of Englebert came at a critical time for both the league, which was in the midst of a labor negotiation, and the New York franchise in particular. The Liberty, one of three remaining original teams, was owned by Jim Dolan, who, one morning in November ’17, issued a press release announcing his intention to sell, but no buyer. What followed was more than a year of uncertainty for the Liberty, playing at the Westchester County Center, with a capacity of less than 3,000, a facility far from the team’s longtime fan base at Madison Square Garden. It was the equivalent of leaving the team by the side of the road.

Joe Tsai is a cofounder of the Chinese tech giant Alibaba. He and Clara purchased the Liberty in January 2019, and Barclays Center as well—thus providing New York with a professional-quality venue. Meanwhile, as they stabilized the franchise, Engelbert and the WNBPA reached an agreement on a long-term CBA in January ’20 that would run through ’27. It included significant increases in the maximum salary, from $119,500 to $215,000, while salary caps increased roughly 30%.

Asked on a January 2020 media call about how the WNBA intended to pay for this, Engelbert said: “This is what I’ll call a multifaceted strategy to transform the league. … Ultimately we need to drive in new fans, more ticket sales, more viewership, drive the value of our franchises and assets up so we can sell the league and sell it successfully. That’s what we’re working on.”

What Engelbert was working on, now that she had locked in fixed labor costs through 2027, was a capital raise, one she hoped would be driven by rising tides of revenues like ticket sales and in-arena sponsorships. New money would allow the league to professionalize an array of areas that have been long neglected, from the league’s digital offerings to WNBA League Pass to how the league sells merchandise.

Less than two months later, of course, the world stopped due to COVID-19. And suddenly, a capital raise served dual purposes: helping the WNBA grow, and covering losses that the league, like all of professional sports, suffered during a time attendance not only fell but was impossible to even have. League operating income, before accounting for profits or losses per team, dropped from $27.7 million in fiscal year 2019 to $11.1 million in fiscal year 2020, according to internal league estimates reviewed by SI.

For teams watching every penny, especially those losing money, this provided a vital new impetus for a capital raise. There are WNBA owners who cannot afford to spend endlessly. But other owners, like the Tsais, increasingly, are playing a different game.

The terms were laid out to owners by early 2021: a $50 million cash infusion, through an investment from a combination of current owners and outside investors, which would call for the league to sell 20% of its total equity, working off a valuation of $200 million.

As the vaccination drive lagged through 2021 and with it, delayed the return of full-capacity WNBA arenas, Engelbert and the league faced pressures on several fronts. Simply conducting a season was its own challenge, while mollifying some old-school WNBA owners as the capital raise talks continued was another.

And while many players continued to loudly call for improving travel conditions—charter flights being the most visible part of that effort—the league found the players had an unexpected source of support for that expense from the new owners who view WNBA teams less as businesses to be managed to the last dollar or places to park losses and more as growth opportunities in a developing economy.

New owners—the Tsais in New York, Marc Lore in Minnesota, Larry Gottesdiener in Atlanta, Mark Davis in Las Vegas—found themselves dumbstruck by how little the WNBA could invest in growth. A sale of 20% of the league’s equity at that moment—especially at a valuation of $200 million—felt like a huge loss, even though new investors outside the league’s owners would not control any votes on the WNBA’s Executive Committee.

On Sept. 13, according to a source familiar with the call, the WNBA Board of Governors considered an unofficial proposal from the Liberty to make charter flights the default travel option for WNBA teams—the Liberty said they’d found a way to get it comped for everyone in the league for three years—but it lacked majority support. (In a statement, the WNBA said: "At no point was there a New York Liberty proposal for the WNBA Board of Governors to consider offering three-years-worth of charter flights for WNBA teams. It was agreed that the Liberty would explore opportunities regarding charter flights and present it to the Board. To date, that has not happened.” SI confirmed this took place from a source who heard the exchange directly.) Some owners worried that players would get used to it, so there’d be no going back, and others wondered whether players might just prefer a salary hike instead.

Christian Petersen/Getty Images

So why are charter flights so important? In a February news conference, Storm guard Sue Bird aptly summed up their significance to the league. “I think what charter flights represent in the world of sports is it gives you a little bit of validation,” she said. “It’s saying that your league is so successful, it has the finances to charter flights, which is incredibly expensive. There’s not many businesses that just charter flights left and right. ... So I think for a lot of us, it would just be an indicator of that. It’d be an indicator of financial success.”

But the Liberty were unwilling to wait for that leaguewide indicator. By the time of that Sept. 13 call, New York had already taken things into its own hands, as Joe Tsai had publicly promised after a late-July travel snafu.

The Liberty, who declined to comment to SI, chartered flights for each road game of the season’s second half, beginning in August with a trip to Minnesota. And eventually, despite a cone of silence over the franchise about it, word got out.

One WNBA front office member noticed that some of the travel details didn’t add up during a New York road trip following the 2021 All-Star break. Then another saw the same. Those officials reported their findings to the league, and the Liberty received inquiries and demands to cease and desist repeated, unauthorized charter travel from Dershowitz, the league’s general counsel.

In a Sept. 21 reply to Dershowitz, Liberty alternate governor Oliver Weisberg wrote in a letter later reviewed by SI: “The focus on objecting to better travel arrangements seems to go against the spirit of what the entire League is trying to achieve under the leadership of WNBA Commissioner Cathy Engelbert.” He continued, “We cannot begin to talk about gender equity until we solve some pressing issues that have put extra burdens on the health and well-being of WNBA players. In the spirit of improving working conditions for our female athletes, we are of the strong belief that WNBA teams should be permitted to arrange travel that is consistent with the fact that they are professional athletes.”

A week later, even as the Liberty were facing potential discipline for the CBA violation, Joe Tsai went public with his support of charter flights on Twitter.

The action by the Liberty alienated even some owners who support the idea of charter flights, while leaving other owners wondering whether the CBA would be enforced at all. But as the playoffs approached, the WNBA did not want a massive off-court story to get in the way of coverage, either.

That gave New York plenty of leverage. So the Liberty, even as they acceded to league wishes and did not charter a flight for their first-round playoff game in Phoenix, to push back on the league’s $1 million fine—not typically a decision with appeals. Ultimately, that led Engelbert, according to multiple participants on a Board of Governors call in early November, to say, “I cut a deal with Joe,” reducing the fine to $500,000, which was relayed to the Executive Committee in a Zoom call that month, with further discussion of what penalties for another CBA violation would be. (The WNBA says $1 million was floated informally but never formally presented to New York as a punishment.)

No lost draft picks. No discussion of whether further sanctions would escalate from additional defiance of the CBA.

One WNBA front office member wondered: For $500,000, can any team do anything it wants to pursue a title? Another wondered why the Liberty had been permitted to participate in the 2021 playoffs at all.

Ned Dishman/NBAE/Getty Images

Meanwhile, the league was facing a revolt over some aspects of its capital raise, specifically on the issue of valuation. A number of WNBA owners wanted to borrow or simply loan the $50 million to the league themselves, rather than sell equity, believing that the value of a women’s sports franchise was far higher than the $16.6 million a pre-raise $200 million league valuation implied ($200 million divided by 12 teams).

That left Engelbert with, in essence, three camps within ownership—those who wanted the capital raise and were willing to participate, those who needed the capital raise but couldn’t or wouldn’t participate, and those who thought the capital raise simply wasn’t thinking big enough.

As this work continued, data points in professional U.S. women’s sports helped bolster the go-big faction. The National Women’s Soccer League, in December 2019, saw Megan Rapinoe’s team, Reign FC, sold at a valuation of $3.51 million. By early ’22, the Spirit, after a pitched battle for control, were sold to Michele Kang for $35 million. Both the NWSL and Premier Hockey Federation, the women’s professional hockey league, kept investment internal and raised significant sums—$25 million by PHF, $100 million by NWSL.

Would some WNBA owners have been more willing or able to bet on themselves without selling equity if not for the difficult 2020 and ’21 seasons, especially if attendance rise had matched the increase seen across the board in television ratings? It’s a question that won’t ever be answered.

Ultimately, the final pre-raise valuation Engelbert and the league landed on rose to $400 million, as detailed in a Dec. 29 letter to the WNBA Board of Governors, requesting their final votes by Jan. 4. (The WNBA maintains that the final valuation was $1 billion. Asked to explain this discrepancy, the league did not provide an on-record response.) The league sold significant equity to everyone from six of the 12 current owners, including the Tsais of the go-big coalition, to outsiders like Condoleezza Rice and even Nike, for a total new round of $75 million in capital. The new entity is owned, according to a league document reviewed by SI, 42.1% by current WNBA owners, 42.1% by NBA owners and 15.8% among the new investors—effectively, that’s including some of the current WNBA owners, as well, who participated in the raise.

“This incredible group of investors we’ve put together here have stepped up in I think a great way to help us drive this growth,” Engelbert told reporters Feb. 3. “It can’t be understated—because we constantly read about women’s businesses struggling and having barriers to accessing capital—that this is the largest capital raise for a women’s sports property. We’re featuring external investors and in-the-family investors through NBA, WNBA owners and former players.”

The same week, NWSL owners committed to $100 million of investment themselves. The new CBA for the NWSL allows for a dramatically expanded salary cap, and notably, a soft one, with allocation money (essentially, padding that allows the team to exceed the cap) giving a team like the Spirit the chance to pay reigning Rookie of the Year Trinity Rodman $1.1 million over the next four years.

Not only is that greater than the WNBA’s max salaries would allow, but it happened after Rodman played just one season in the league. The fear was that overseas money could lure her away. With the WNBA’s CBA closing down the ability for players to report late from overseas commitments in the W offseason, this is a problem the league will face soon, as well.

Increasingly, the WNBA owners most interested in aggressively advancing the league’s spending aren’t willing to keep those conversations private.

Barry Gossage/NBAE/Getty Images

In an early February Zoom with media, Davis recalled a conversation he’d had, before his purchase of the Aces, with Bill Hornbuckle, an executive with then Aces owner MGM.

“I kept telling him every game as a fan, that you’ve got to pay these players more money. You’ve got to pay these players more money. And he finally looked at me and said: ‘Listen, if you [want them] to be paid more money, buy the team, and you pay them.’ And eventually that’s what we did. And the problem that I ran into right away is I wanted the women to make more money, but it’s collectively bargained, and there’s a limit on the amount that we can pay them right now.”

So Davis went out and paid his new coach, Becky Hammon, $1 million a year, because coaching salaries aren’t in the CBA. And charters still are, of course, but Davis wants that to change, too.

“The players do deserve more money. … They don’t need to be flying on commercial flights,” Davis says. “We should have charter flights.”

New York spent the offseason dreaming big, including a pursuit that led to a meeting with the Storm’s Breanna Stewart, a generational talent and former MVP who grew up just a few hours away from Barclays Center in North Syracuse. While Stewart opted to re-sign with Seattle for what is almost certainly teammate Bird’s final season, she committed for just one year.

In the meantime, the Liberty added Stewart’s former UConn teammate, Stefanie Dolson, a center whose game would fit well with Stewart’s in the New York frontcourt. Dolson had played for the Sky, winning a WNBA title in Chicago in 2021. So why did she come to New York?

“The entire franchise, you can tell they just really care about their players,” Dolson told SNY’s Maria Marino on Feb. 15. “They care about the level of basketball they put out on the floor, which we can produce the best when we’re not really worried about the other stuff, like where are we going to practice, how are we traveling, what’s the schedule, just all that other stuff. When we can focus on just basketball, we can put out the best product.”

Editors’ note, March. 1, 5:09 p.m. ET: This story has been updated to reflect the WNBA’s Tuesday statement about the New York Liberty’s unofficial proposal to make charter flights the default option for teams for three years.