Coaching kids sports comes with lots of challenges. You have to keep a keen eye on them so nobody gets hurt. You have to show authority so they don’t start wreaking havoc on a soccer pitch. And then there’s nutrition: kids need energy when they’re physically active, so they have to snack and drink. Healthy stuff, preferably.

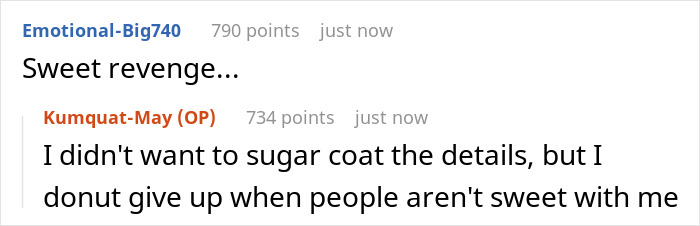

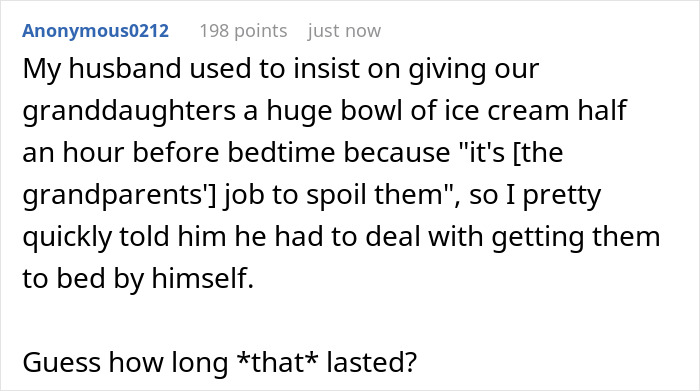

But the parents in this story didn’t think so. They got mad at the coach for banning sugary drinks and snacks because they thought it infringed on the kids’ right to eat what they want. Not wanting to deal with the kids’ sugar high and the subsequent crash, this man dealt the parents an Uno Reverse Card and made them deal with the hyper kids instead.

Controlling a bunch of kids is hard as it is, and it’s even harder when they’re being hyperactive

Image credits: YuriArcursPeopleimages (not the actual photo)

This coach decided to ban sugary snacks so that he didn’t have to deal with their sugar crash

Image credits: ASphotostudio (not the actual photo)

Image source: Kumquat-May

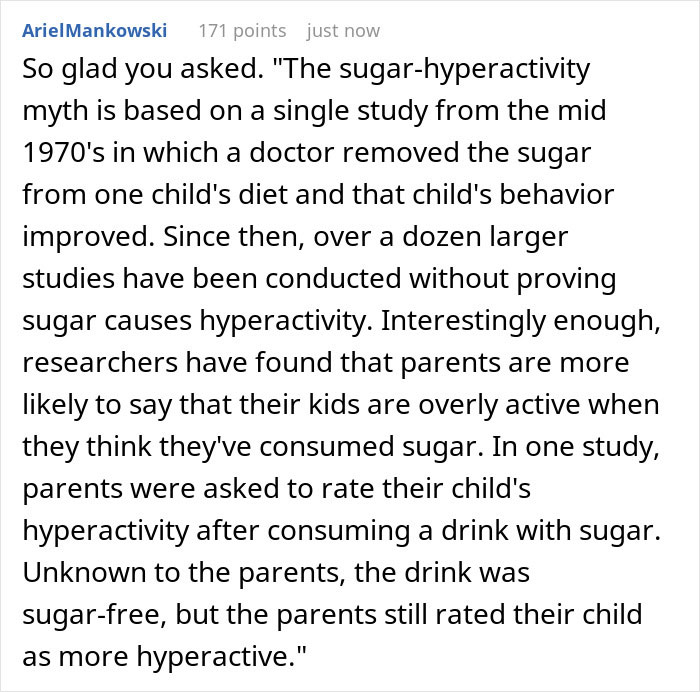

Anecdotal evidence shows that kids get hyperactive after eating sugar, but science might say otherwise

Image credits: Alina Rossoshanska (not the actual photo)

The debate around whether kids really get a sugar rush is quite a heated one. People on one side of the argument argue that this is a myth. Their opponents claim that the research is inaccurate because corporations like McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, and Mars funded it. So, let’s explore the whole thing from the very beginning.

It all started with the Feingold diet in 1973. Allergist Benjamin Feingold, M.D., published a study in which he made a connection between sugar and hyperactivity in children.

“[The mother’s] fair-haired, wiry son loved soft drinks, candy and cake — not exactly abnormal for any healthy child. He also seemed to go completely wild after birthday parties and during family gatherings around holidays,” Feingold wrote in his research.

Feingold didn’t advocate that parents eliminate sugar from their children’s diet. He did, however, suggest limiting the intake of salicylates, food colorings, and artificial flavoring.

A 1978 study supported this claim. These researchers found that sugar diets caused a spike in insulin, which, in turn, resulted in higher production of adrenaline and hyperactivity.

Scientists debunked the studies that found a correlation between sugar intake and hyperactivity

Image credits: Mariana Kurnyk (not the actual photo)

Two separate studies in 1994 and 1995 set out to oppose the aforementioned research. The 1994 study, which The New York Times calls “extraordinarily rigorous,” proved that neither sucrose nor aspartame affect children’s behavior.

A meta-study one year later supported their claims further. An Australian study in 2018 also found that “total dietary sugar consumption does not influence sleep or behaviour.” And many other experts reiterate that the link between sugar and hyperactivity is a myth. For example, Mark Corkins, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition, told National Geographic that there’s “no association – none.”

According to Yale Scientific Magazine, children who had sugar had higher levels of adrenaline, which might contribute to the myth. “Sugar is quickly absorbed into the bloodstream, blood sugar rises quickly, which can lead to higher adrenaline levels and thus symptoms similar to those associated with hyperactivity.”

Children can act hyper even when they don’t consume any sugar

Image credits: Ketut Subiyanto (not the actual photo)

Experts say that it’s not so much about the intake of sugar as it’s more about the expectation that kids will act hyper after eating sugar. Another study in 1994 showed parents’ bias towards their kids’ sugar intake. Mothers in this experiment reported that their sons were hyperactive because of sugar when, in reality, all the participants were given the placebo.

“Even children know the power of their brains. They say, ‘I ate all this candy, I’m never going to go to sleep!'” Sabiha Kanchwala, M.D., general pediatrics specialist at Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital, said. “We know sugar in and of itself is not what’s making your child hyper, but there are a variety of other things leading to their excessive activity.”

Mark Corkins invites us to consider what we associate with kids eating candy. Birthdays, parties, BBQs, family reunions, Christmas, Thanksgiving – social gatherings. “When we look at the times that kids have high sugar intake, it’s usually associated with when they’re going to be hyper, even if you didn’t give them any sugar,” he said. Dr. Kanchwala says that the more possible culprits of hyperactive behavior in children can be lack of sleep, stress, trauma, or even caffeine.

But the sugar crash, on the other hand, is very real. Although, it mostly affects people with diabetes. It’s the fatigue, anxiety, headaches, and general irritability one might feel after eating a lot of sugar. Natasa Janicic-Kahric, an associate professor of medicine at Georgetown University Hospital, told The Washington Post that “about 5 percent of Americans experience [a] sugar crash.”

Commenters shared similar experiences and praised the OP for how he dealt with the parents