The UN secretary general Antonio Guterres has made an urgent call for a global action plan to tackle extreme heat. His recent speech in New York came as the average temperature of the Earth’s surface has broken records twice and followed 12 consecutive months as the warmest months ever.

Extreme heat is how most people experience the impacts of climate change. It kills half a million people a year – about 30 times more than tropical cyclones, as Guterres noted. But beyond the tragedy of the rising deaths, extreme heat undermines our productivity, making some jobs too dangerous to do. That puts pressure on every part of our economies and lives.

This latest global call to action emphasises four critical areas of response: protecting the vulnerable, protecting workers, boosting resilience and limiting further warming to stave off an era of what Guterres has termed “global boiling”.

Read more: Searing summers in European cities pose a continent-wide health inequality challenge

The most vulnerable people include the young, sick, elderly, those on low incomes who can’t find safety in a cool place, and pregnant women. These particular groups are even more vulnerable if they live in rapidly urbanising cities in countries where excruciating heat shocks are becoming more frequent, intense and long-lasting. Women tend to face bigger burdens from extreme heat – most agricultural workers in fields are female and in towns and cities women carry out of the most domestic work.

The solution, according to the United Nation’s Environment Programme, is to increase investment in cooling technologies, improve urban design, and green towns and cities. That means more trees and green roofs, different building materials and low-carbon transport. It also means investing in more and better hydro-meteorological systems or tech that can understand, predict and warn citizens of extreme weather events, including heatwaves and droughts. Today, only 10% of African countries have adequate data hampering their preparedness for heat shocks.

Better and earlier warnings can enable health systems to prepare and better cope with the human health consequences. Together, the World Meteorological Organization and the World Health Organization estimate that scaling up health warning systems in 57 countries would save almost 100,000 lives each year.

Naming extreme heat events makes it easier to communicate the risk to the public – but that’s not the norm yet in most parts of the world. In the US, heat kills more people than hurricanes and fires, both of which get named, while heatwaves still don’t.

Workers also need better protection. An estimated 70% of the global workforce is exposed to extreme heat – that includes construction and agricultural workers, warehouse and distribution centres and office workers.

Changes in occupational health and safety standards have been slow to materialise, but unions and worker organisations are mobilising to force employers and governments to improve working conditions. Governments must set standards and employers need to understand that productivity is handicapped by extreme heat, and by not giving workers water breaks and changing shifts or working hours to avoid the worst of the heat.

City leaders and mayors are often at the frontline of boosting resilience. They can appoint extreme heat officers, develop heat and resilience plans and coordinate communities, employers and public services. The key will be to be able to respond quickly to extreme heat events, protecting the vulnerable while keeping services running.

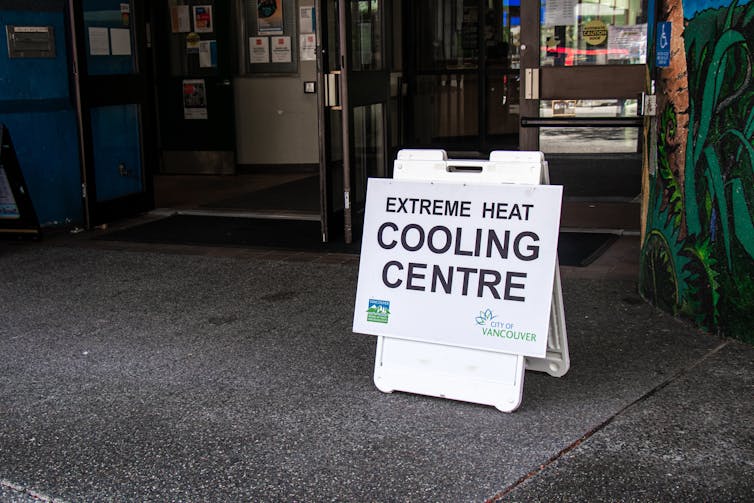

But even in cities with advanced plans, many initiatives are inadequately financed or staffed. Cooling centres – publicly accessible places where people can shelter in the cool – may remain closed at night, even when night-time temperatures remain high. The state of city and municipal finances is key and funds need boosting by partnership with central government.

A pact for the present

Guterres reiterated his call for governments to act on their commitments at the COP28 climate summit in 2023 to limit the use of fossil fuels. Initially, that can be done more quickly by reducing emissions of short-lived climate pollutants such as methane.

Eighteen years ago, an influential climate report called The Stern Review highlighted that the cost of inaction on climate change was known to exceed the cost of action. Yet, despite nations agreeing to limit warming and leave no one behind in the 2015 Paris agreement, the international community is failing to deliver.

Global heating already results in productivity losses and reductions in GDP. It disrupts education too. In the Philippines, all public schools were closed for two days with lessons moved online during a heat wave in April. In March, schools were closed across South Sudan and parents were instructed to keep children inside, while this week, all schools closed across Kashmir, India as temperatures rose.

In this year of many elections, election workers, including those operating polling stations, will be among those feeling the direct effects of the heat most acutely, along with farmers, expectant mothers and nursery school children.

This latest call to action on extreme heat is principally directed at heads of government. They will next meet the secretary general in September at a gathering of the UN general assembly. On their agenda will be agreement on a pact for the future at a special summit.

Extreme heat is the future arriving today. Implementing last week’s call to action would be a pact for the present. The good news is that mayors and heat officers, doctors, investors and innovators in cooling solutions are all trying to protect people, food chains, vaccines and medicines from extreme heat now. With more support, they can at least begin to save lives and livelihoods. But to turn the thermostat right down, global emissions need to be cut now and in the future.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get our award-winning weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 35,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Rachel Kyte is affiliated with Climate Resilience for All a not for profit organization with a mission to protect the health and livelihoods of women and vulnerable communities from extreme heat. Rachel Kyte is a high level champion of the UN Climate and Clean Air Coalition.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.