As students and teachers prepare to go on holidays, there’s a disagreement raging over a new school funding deal for 2025.

Queensland, New South Wales, South Australia and Victoria have all refused to sign up to the Albanese government’s offer for the next round of funding. This offer would see the federal government contribute 22.5% towards government school funding, up from 20%. But these state governments think it should be 25% instead.

As the disagreement rolls into next year, many Australians may not realise the federal government hasn’t always contributed to school funding.

The federal government has only been funding schools for 60 years. And it would not have happened if not for a Soviet satellite, an Australian prime minister and some science labs.

Schools have historically been funded by the states

Before 1964, the federal government resisted involvement in school education.

Legislation between 1872 and 1895 made colonial and then state governments responsible for government schools. Government funding for non-government schools was abolished as a result. So all independent schools, including Catholic parish schools, had to rely on fees and philanthropy.

But this all changed during the 1963 federal election campaign and the subsequent States Grants Act of 1964.

Enter the space race

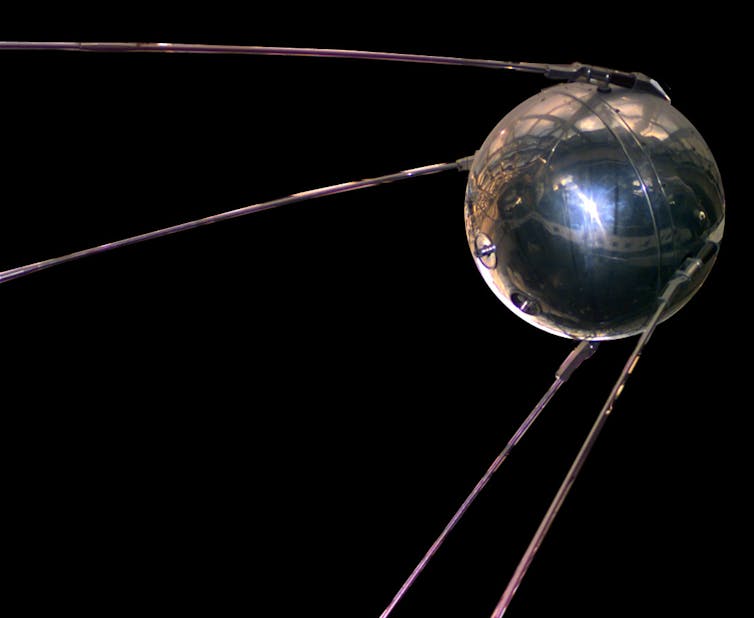

In 1957 something dramatic happened.

At the height of the Cold War, the Soviet Union launched the first satellite, Sputnik. The then Liberal Prime Minister Robert Menzies called it a “spectacular act of technology and propaganda”. But others bluntly argued it signalled the failure of the West to keep up with science education. As American physicist George Henry Stine reportedly said: “Unless the US catches up fast we’re dead”.

Fortunately, Menzies had already commissioned Sir Keith Murray from the United Kingdom to review the state of Australia’s universities in 1956.

The Murray report, tabled a month before Sputnik, warned of weaknesses in Australian science education.

In a foreshadowing of concerns about students’ STEM skills today, the Murray report showed the number of students studying physics and maths was low. First year failure rates in university science courses were high because the students were not properly prepared at school. Science teachers were insufficiently trained. The curriculum was outdated and facilities and equipment were either inadequate or nonexistent.

In other words, in the age of Sputnik, science education was not good enough.

This was especially the case in girls’ schools (again echoed in today’s concerns about a gender gap in science achievement). Girls usually studied biology if they studied science at all, as science was seen as “better suited to boys”. The number of women who became science teachers was very small and there was little financial incentive to do so.

Schools had no labs to teach science

By far one of the greatest problems for Australia was the lack of suitable laboratories in schools to teach science.

The problem was so acute, headmaster R.L. Robson (from elite Sydney boys school Shore) and CSR chair F.E. Trigg established The Industrial Fund, to raise money to build science laboratories in “schools of standing”. The fund successfully raised £623,000 to support 37 projects in large private boys’ schools between 1958 and 1964. No girls’ schools were funded.

Menzies was well aware of The Industrial Fund because he was regularly invited to open the new buildings.

So, not only did Menzies understand the importance of science education for national defence in a post-Sputnik world, he was aware of Australian education failings from the Murray report. He was also reminded of a way to fix this, every time he opened a new science laboratory.

The 1963 election

Then a domestic political opportunity presented itself.

In 1963, the federal executive of the Labor Party reversed a NSW State Labor Party decision to support government aid for science to non-government schools. This gave Menzies a unique and timely electoral window to differentiate his party.

In the election campaign of 1963 Menzies proposed to build science laboratories in high schools “without discrimination”.

Historians have long argued Menzies’ policy shift was all about courting the Catholic vote in the tight 1963 election (which he ultimately won).

But the States Grants Act also went beyond Catholic schools. Students benefited regardless of whether they attended a state school or not and whether they were boys or girls. In the end, more than 500 schools either received assistance to build a lab or were recommended to receive it.

From labs to libraries and beyond

Commonwealth assistance to schools expanded rapidly in the late 1960s.

In 1968, the federal government began a grants program for school libraries. Per capita grants were introduced for private schools in 1969 and for public schools from 1972.

What had begun as a specific scheme to improve science education grew into an ongoing commitment to support school education in general.

As today’s school funding wars continue into 2025, it is worth remembering the unusual history behind the federal government’s involvement. And how for some, it is not a natural funding source for the school system.

Meanwhile, increasing students’ skills and engagement with science has been a concern in Australia for more than six decades.

Jennifer Clark does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.