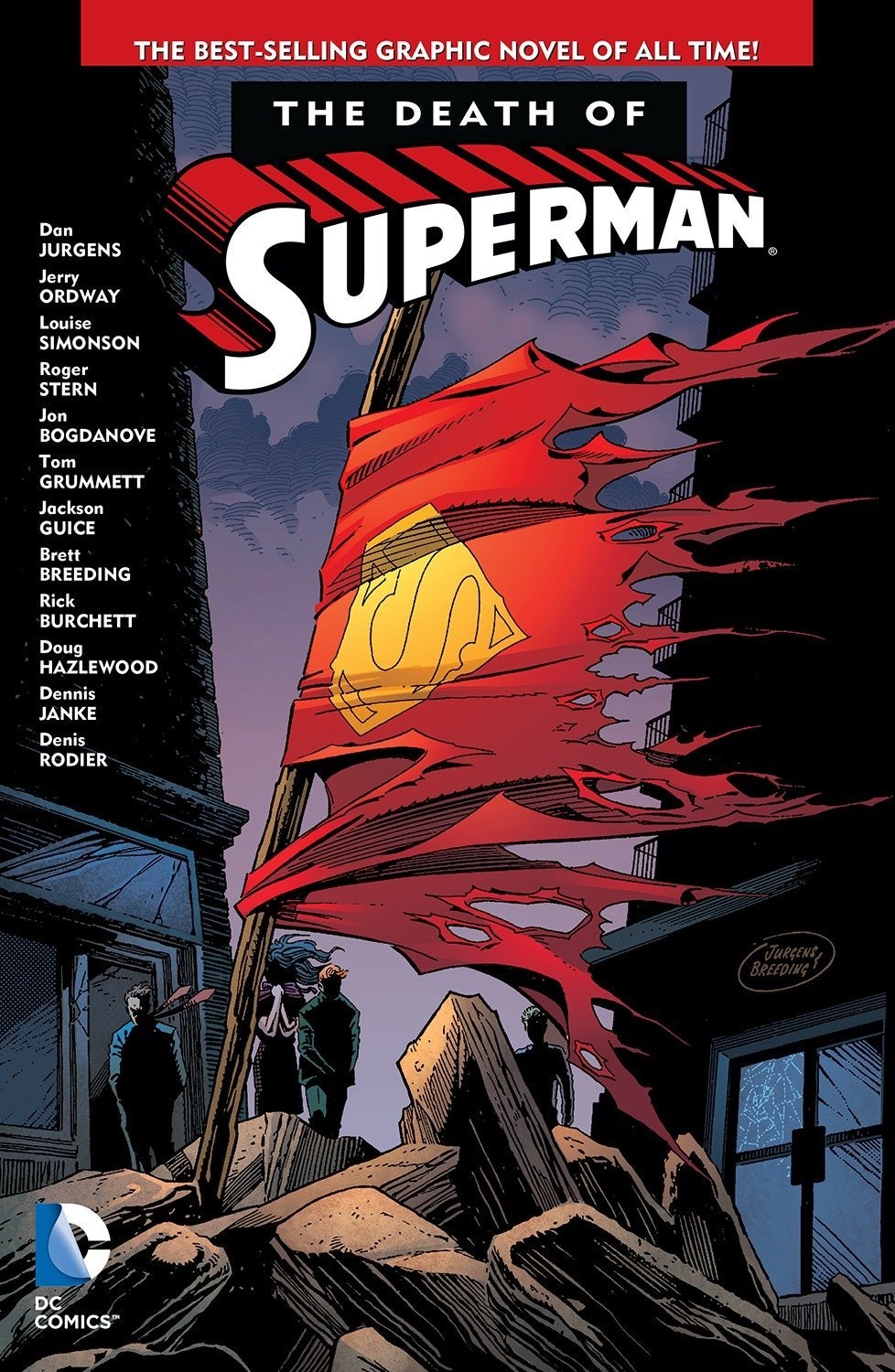

In 1992, DC Comics crossed a then-unthinkable line.

Clark Kent. Kal-El. The Man of Steel. Superman, the gold standard superhero and the fictional character mapped over the public consciousness as the ultimate Samaritan, would die.

After years of saving Metropolis from repeated destruction, Superman was felled by a new character, aptly named Doomsday, who donned gym shorts and a skullet. A fictional event so startling that it pierced the public zeitgeist, it was the first time I can remember comic books making the evening news.

“Did they really kill off Superman?”

But a year before Superman died in the comics, the Canadian rock band Crash Test Dummies eulogized him in “Superman’s Song” off their debut album, The Ghosts That Haunt Me. Describing Kal-El’s hypothetical funeral, lead singer Brad Roberts mourned in his signature baritone: “Sometimes I despair the world will never see another man like him.”

You’d think someone would have reached out to Roberts back when he managed to predict the Man of Steel’s demise, yet it somehow fell on this reporter to break the news three decades later.

“Did they really kill off Superman?” Roberts asks when I make contact with the Winnipeg band’s frontman over the phone.

But despite missing out on the event he accidentally prognosticated, the true story behind “Superman’s Song” reveals a pivotal moment in our shared cultural history. And, at least according to Roberts, it’s been downhill for the genre ever since.

When Roberts was 8, his mother would reward his dentist office visits with a comic book. One issue stuck with him to adulthood, a comic in which the mighty Superman is challenged by Solomon Grundy, a hulking, ghoulish, resurrected corpse with the curious disposition of a child.

“It scared the hell out of me,” Roberts says. “I was just a kid. Needless to say, I didn’t follow up that closely with Superman’s career after I wrote the song. I kind of left it at that.”

The press didn’t follow up with the band when Superman bit it in the comics, but they did challenge Roberts on whether Solomon Grundy (originally a Green Lantern foe) ever went toe-to-toe with Superman. Frustrated, Roberts fished out his childhood comic and began faxing the pages to any writer who bothered him about it.

“He pursues good for its own sake.”

“The media came out and said, ‘Brad Roberts is a farce,’” the singer recalls. “That’s what bothered people if you can believe it. I can hardly fathom the response.”

He adds, “I ultimately won the day.”

(Green Lantern also makes an appearance in the music video for “Superman’s Song” as one of the pallbearers, alongside Wonder Woman and the Green Hornet.)

But Roberts didn’t write the song to boast any comic book bona fides, and the lyrics aren’t really about the Superman from the comics. It certainly isn’t about anyone who was resurrected quite as easily.

While working in a bar in Winnipeg, Roberts overheard a song on the radio dunking on Tarzan (the lyrics he recalled and sang to me sounded like Timbuk 3’s “Tarzan Was a Bluesman”). Edgar Rice Burroughs’ colonialist archetype similarly got under Roberts’ skin, so he began writing his first song, which criticized the freewheeling ape-man.

Roberts couldn’t help but see contrasts between Tarzan, a self-appointed king living carefree in the jungle, and Superman, who uses his alien powers to defend the common people of another planet. The song would pivot toward celebrating Superman, a type of person who was also fading in the real world’s public sphere.

“It’s pretty deep psychology for a comic book.”

Roberts attributes this shift to something he learned while studying English literature and philosophy at the University of Winnipeg.

“One of the things that impressed me was this distinction between the idea of doing something for a reason versus doing something for one’s own sake,” he says. “In the case of Superman, he pursues good for its own sake. It’s not so he can get something else. The end in itself.

“One of the things that the song gets at is this kind of decaying sense of civic responsibility, where characters like Superman are no longer valued.”

Much has been written about the significance of Superman beyond his comic book adventures. Created by two sons of fleeing Jewish immigrants, Superman is now recognized as one of the pivotal tales of Jewish diaspora right alongside Marvel’s Magneto. An alien from a shattered world, Superman not only wants to assimilate with humans, he aspires to be the best kind of human possible. Superman is someone who not only adores his adoptive home but will fight against gods and monsters to see it thrive.

“It’s pretty deep psychology for a comic book,” says Roberts. “I think the lyrics hold water today, and that’s not always the case with one’s first songs.”

There have been other radio singles about the notion of Superman falling or dying: 3 Doors Down’s “Kryptonite,” Our Lady Peace’s “Superman’s Dead.” The thought of an invincible hero being taken down haunts us far more than the moment it actually happened.

In the comics, the news of Superman’s death was premature. After a convoluted soap opera involving clones, robots, and Kryptonian technology, Superman returned alive only a year later, sporting a black costume and a grungy mop of hair. In anthologies, video games, and direct-to-DVD animated films, it is anticlimactically branded The Death and Return of Superman. A sequence where Superman kisses extinction only to bounce back was depicted in the 2006 film Superman Returns and across Zack Snyder’s Justice League saga, the latter evoking Doomsday himself.

Superman also faces his mortality in Grant Morrison’s 2005 series All-Star Superman. There, Clark Kent spends his final days contemplating life, showing earthlings what’s worth living for, and visiting friends, family, and enemies.

The 1990 comic book event proved to be little more than a stunt, something extremely vogue at the time. After word got out that Superman’s first appearance in 1938’s Action Comics #1 could fetch a fortune, a frenzy of comic book collection and evaluation kicked off. Entrepreneurs called up their parents to check the attic as soon as possible. This prompted DC and Marvel to conjure up as many events, new characters, and milestones as possible, luring in collectors who imagined themselves as putting in an early stake. Beanie Baby stuff, essentially. When the trend began to feel like a bust, this new wind for superhero comics tore through the sails. Marvel filed for bankruptcy in 1996.

“Hero worship seems to have switched over to the bad guys”

Roberts hasn’t seen any Marvel or superhero movies of the last few decades, but he has noticed that the characters who capture the public imagination have also shifted since his eulogy. Leading Marvel’s box office charge was not an everyman or salt-of-the-earth reporter like Superman (or even the earnest, working-class Spider-Man) but billionaire industrialist and weaponsmith Iron Man, whose tenure in Hollywood mirrors the growing cult-like adoration for certain tech moguls and elites.

Meanwhile, DC struggles to find a compelling story for the heroic Superman to bring to the big screen, opting instead to portray someone with that much strength and love in their heart as a tyrant in waiting. Stories of Superman giving into the life of an authoritarian are spelled out in multimillion-dollar entertainment like Snyder’s Dawn of Justice or the Injustice video games where Superman goes Tarzan and names himself the god-king of where he landed. He becomes a wild dog who needs to be put down, usually by Batman in a sequence first popularized by Frank Miller’s 1986 comic The Dark Knight Returns.

DC’s most popular character isn’t even Batman. It’s not a superhero at all. For the last 20 years, people see themselves in the Joker. The clown prince of crime. Individualist as simple, murderous id, and a character that for 10 years has been revered as an Oscar opportunity for leading actors. The Joker’s juvenile compulsion for violence is not unlike Grundy’s, who kills others like teasing the wings off of a housefly.

“Hero worship seems to have switched over to the bad guys,” says Roberts. “I think that’s telling.”

Roberts might be disappointed with the direction of superhero stories in the 21st century, but he’s not surprised.

“I didn’t really expect to create any change with the song, nor did I expect things to happen in a good direction,” says Roberts. “I’m a little too cynical for that.”

That this is where the public imagination stands, he says, not necessarily a hunger for violence but endless self-gratification in the likes of Joker, Grundy, or Grand Theft Auto. He and I agree that art lives downstream from politics, but that art can be used like tea leaves to have a better understanding of what’s brewing upstream.

“The old heroes are a little bit tired out,” Roberts says. “At the same time, as comics become this microcosm of culture, it is indeed disheartening to see that rampant individualism seems to be taking even more root in our culture.”

It shouldn’t be too surprising that tragedy and crisis becoming excuses for fewer social safety nets, instead of more, may lead to a more short-term thinking, pleasure-seeking, Jokerfied world. It can feel like Superman really did die in the early ’90s, but it wasn’t the comic books that killed him.

The Inverse SUPERHERO ISSUE challenges the most dominant idea in our culture today.

.png?w=600)