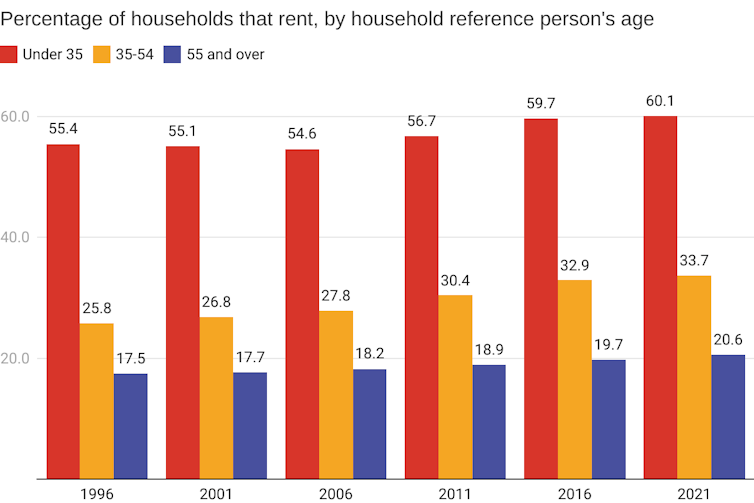

Private rental forms an increasingly large part of our housing system. Just over a quarter (26%) of Australian households – 2.4 million of them – live in privately rented dwellings. And increasing numbers are renting long-term.

These trends are reshaping expectations of private rental housing. Residential tenancy reforms that are rolling out around the nation – albeit in slightly variable ways – are an important part of this national change.

These reforms are important to ensure tenants are safe, secure and happy in their homes. Insecure and poor-quality housing can harm renters’ health and wellbeing.

Read more: Stability and security: the keys to closing the mental health gap between renters and home owners

Importantly, the reforms also shape the role and responsibilities of investor landlords – “rental providers” as Victoria recently renamed them – and the expectations we can have of them. These changes have implications for the support they need to be good landlords.

Using 2019-20 ABS Survey of Income and Housing data, we estimate around 14.8% of households were residential investor landlords who received rental income. This is an increase from 13.8% in 2015-16 and 10% of households in 2003-04.

Unlike investments that do not directly affect others, investing in housing means providing other people with a home.

Tax concessions for investor landlords are generous by international standards. In 2016, capital gains tax discounts and negative gearing were together estimated to cost the budget $11.7 billion a year.

Current data are difficult to access. Recent independent analysis by the Parliamentary Budget Office commissioned by the Greens shows 57% of negative-gearing deductions go to rental investors in the top 20% of income earners, with men benefiting most.

In return for these tax breaks, there are expectations about the standards of housing that investors provide.

Read more: Fall in ageing Australians' home-ownership rates looms as seismic shock for housing policy

What are the key issues for reform?

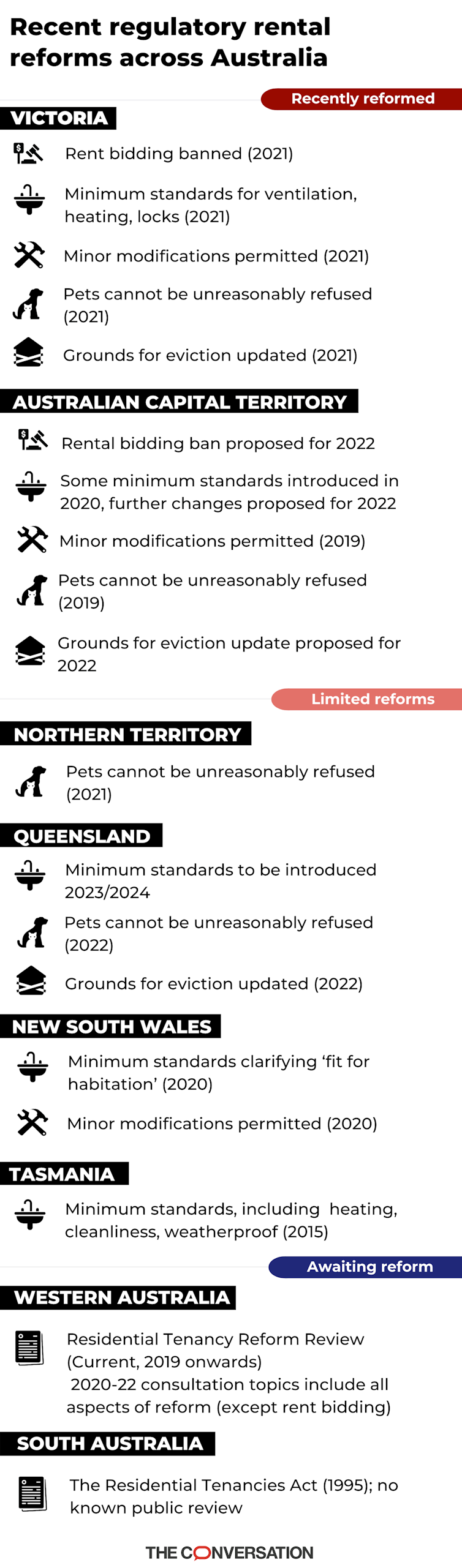

We see five key changes in many state and territory reforms so far. These should be central to further reforms:

“rent bidding”: this practice has plagued access to private rental tenancies as vacancy rates have fallen nationally, but new laws include provisions to prevent real estate agents and landlords letting property to “the highest bidder”

minimum standards: these cover conditions of dwellings, including heating, safety/security and in some cases, such as the ACT, a focus on sustainability and reducing appliance energy use

property modifications: the most progressive reforms allow tenants to make reasonable alterations to properties – such as hanging picture hooks or having vegetable gardens – and generally require them to return properties to the original form when the lease ends

pet inclusion: Australian households increasingly see their pets as part of the family and many tenancy reforms put the onus on landlords to establish grounds for refusing pets

more secure leases: a major change in all recent reforms, with the striking exception of New South Wales, is the removal of “no grounds eviction”. Landlords must now provide one of several regulated reasons (such as returning to live in the property) for asking a tenant to vacate a property during a lease. Importantly, reforms are also introducing a new ground for asking tenants to vacate property, where they are deemed dangerous to property and/or unsafe for neighbours.

Read more: Australia's housing laws are changing, but do they go far enough to prevent pet abandonment?

What is each state and territory doing?

Below is a snapshot of recent regulatory reforms across Victoria, NSW, ACT, NT, pending reforms in Queensland , and lessons for future reforms in Western Australia (currently under review), Tasmania and South Australia. It summarises key changes for tenants and investors since tenancy reforms began around 2019.

Helping landlords to be better rental providers

Reforms to residential tenancy laws are practical measures to enhance the housing of tenants. The changes recognise that renters have often been left behind in the rapid financialisation and growth of the sector. The reforms clarify landlords’ responsibilities to provide decent housing, in return for currently generous tax concessions.

Much of the commentary on these reforms can take an “us and them” approach to tenant and property owner rights. This is unnecessary and a missed opportunity to educate investor landlords in their essential role as housing providers. It’s clear an important element of the reforms is ensuring investors understand their role and have capacity to fulfil it.

It is too early to assess the direct impacts of recent reforms, not least because they have come into effect in the years disrupted by COVID-19. However, by international standards the reforms are moderate.

Real estate industries and financial sectors – along with consumer affairs offices and tenant advocacy in each state and territory – can usefully support people who are looking to invest in residential property to understand their role and responsibilities as rental providers. States including Victoria and Tasmania have appointed a residential tenancies commissioner. Other jurisdictions could consider doing the same to offer additional support.

Key elements of effective support would ensure landlords have:

full information about the upfront and ongoing costs of delivering housing that at least meets minimum standards of liveability and safety

adequate income and resources to respond promptly to the need for any property repairs and improvements

an understanding of their important role as long-term providers of housing and home.

Tenants have to provide detailed evidence of their capacity to be a tenant. Rental providers should face similar requirements to rent out a property.

Wendy Stone receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC), the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), Housing for the Aged Action Group and Kids Under Cover and has previously received funding from the Victorian Government.

Terry Burke has received funding from AHURI, ARC, and Homes Vic but has no current funding. He is affiliated with the Community Housing Industry Association Victoria (CHIA Vic) for which he provides volunteer professional development training.

Zoe Goodall has received funding from the Victorian Government and the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) and receives an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.