Kelvin Sampson settles into a chair in his office and offers a succinct review of his Cougars’ 17-point victory against Wichita State the night before. “We played like s---,” he says. There is a scowl on his face, but it’s quickly replaced by a small smile and a brief chuckle.

“We play like s--- a lot,” he adds.

The laughter reveals multiple truths: Sampson’s 31–3 team has reached such a stature that winning by 17 can be considered flush-worthy. Sampson doesn’t care if his team plays like poop as long as his team wins—he relishes it, actually, since it meshes with the team ethos; no program in college basketball wins more games in this manner than Sampson’s over the past six seasons.

Houston is 174–33 in that span, an .841 winning percentage that is topped by only Gonzaga’s .891. While Mark Few’s program is renowned for playing pretty basketball, Sampson’s is the foremost practitioner of winning ugly.

The Cougars have been to three Sweet 16s, two Elite Eights and one Final Four in the past three NCAA tournaments. Now the 67-year-old Sampson has his best Houston team—probably his best team, period, in 34 years as a college head coach—despite its propensity for toilet ball.

Jerome Miron/USA TODAY Sports

The program that excels at playing like No. 2 is a No. 1 seed for the first time in 40 years and is taking aim at a serendipitous Final Four in its hometown, with more than half a century of unfinished business to atone for. The history of men’s college basketball cannot be written without the Cougars, who have been involved in some watershed moments throughout NCAA tournament history—yet they’re nowhere to be found on the roll call of national champions.

“For the City” is the motto the urban program branded five years ago, picking up a sentiment expressed on social media by guard and Houston native Galen Robinson Jr. as the Cougars were beginning their ascent to national prominence. But this season is also for Big E and Guy V and Phi Slama Jama—for all those great Houston teams whose path to a national championship was always blocked at the final step?

The time to take that step is now. Perhaps now or never.

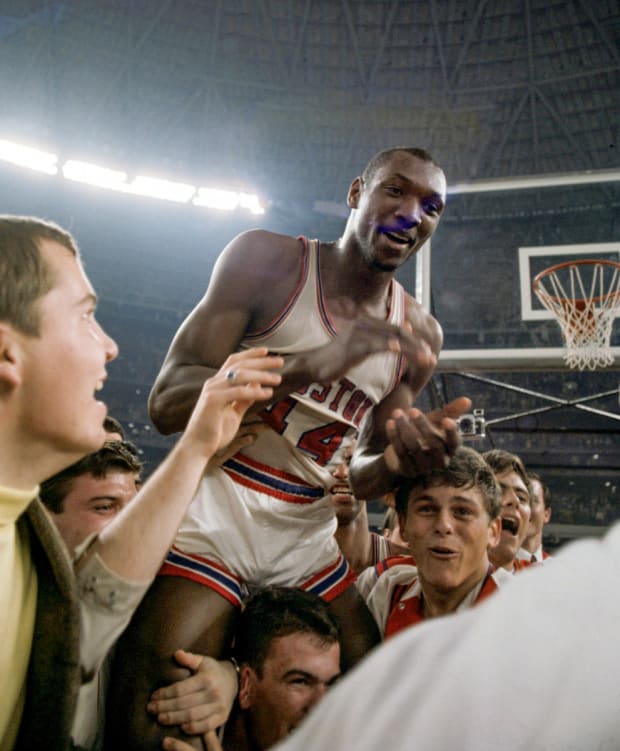

Elvin Hayes sits courtside for home games, a living monument to the birth of Houston basketball as a national power. He is a huge man stooped a bit by age, but his 77-year-old mind is still sharp—and his critiques are still blunt. When asked whether the current Cougars could beat the teams he played on in the 1960s, he laughs and answers quickly.

“No, I don’t think so,” the Big E says. “They’ve got a good basketball team, and it’s been great to watch them every night. But we had a great team. That’s the difference.”

A man voted one of the NBA’s all-time top 50 players probably knows what he’s talking about. He did play on great teams, advancing to three straight NCAA tournaments and the first two Final Fours in program history. But the Cougars’ path to a title was blocked, repeatedly, by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (then Lew Alcindor), John Wooden and UCLA.

It took arguably the greatest college player and inarguably the greatest college dynasty to keep Hayes from a national championship, but what a trail those Cougars blazed to the doorstep of history.

When Hayes and fellow future NBA player Don Chaney arrived as freshmen at Houston, they were part of a vanguard of Black players who would change the sport in the South. Athletic integration would come slowly and painfully in many places, but the urban schools were pushing ahead of the state universities in smaller towns.

Black athletes had already become stars at city schools in other parts of the country: Bill Russell and K.C. Jones won NCAA titles at San Francisco in 1955 and ’56; Elgin Baylor took Seattle to the championship game in ’58; Oscar Robertson led Cincinnati to the Final Four in ’59 and ’60. It took a while longer below the Mason-Dixon Line.

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated

Louisville welcomed its first Black basketball players in 1963. Memphis State would do the same in ’65. In between those two, in the fall of ’64, Houston coach Guy Lewis brought Hayes to campus from tiny Rayville, La., and Chaney from Baton Rouge. “Everybody knew Don. Nobody knew Elvin Hayes,” Hayes says. “It gave me the opportunity to kind of sneak in and become the player I became.”

A powerful and athletic 6'9", Hayes didn’t take long to develop on the court. The transition was more difficult everywhere else. Rayville, located between Monroe, La., and Vicksburg, Miss., was isolated and segregated. Moving to a big city and joining an overwhelmingly white student body was culture shock.

“I had never been around whites at all,” Hayes says. “In my hometown, it was like everybody was separated. I brought that with me.”

While Hayes was struggling with white people on campus, they were struggling with him. He remembers being in class with Chaney one day and seeing a white girl visibly shaking. He asked her what was wrong. Her answer: “You.”

At one point, Lewis, who was white, brought Hayes into his office and asked whether he had made a mistake recruiting him to break the basketball color barrier at Houston. “What have I done to you?” Hayes remembers his coach asking him. Lewis encouraged Hayes to try to relax, let down his guard and open up to his new surroundings and peers.

That counseling helped, but Lewis couldn’t insulate his Black players from the racist realities of the 1960s in that part of the country. Hayes recalls the Cougars going to a restaurant in Shreveport—not far from where he grew up—and being told, along with Chaney, that they could not enter with their white teammates. He recalls his parents not being allowed into hotels to see him.

Hayes’s voice is seemingly matter of fact in recounting those stories. If he harbors bitterness, it’s not evident. But he hasn’t forgotten.

“We went through some things you’d maybe not think you should have to,” he says. “But we were fortunate not to have any bad things happen. It was all part of what we knew we had to go through.”

On the court, Hayes was a tower of power. He averaged 27 points and 17 rebounds as a sophomore, his first year on the varsity team (freshmen were ineligible then). His stats were similar the next season, but the team around him was better.

The Cougars were ranked within the top 10 all season, climbing as high as No. 3, and entered the NCAA tournament with a 17–3 record. Three victories landed them in their first Final Four, in Louisville, for a semifinal game against No. 1-ranked undefeated UCLA and Abdul-Jabbar. The Bruins won by 15 points on their way to the national title. But with Hayes and Abdul-Jabbar returning to college the next year, a seed was planted: How about scheduling a game between the two best players in the country? A big game?

Houston proposed the matchup, and proposed it on a grand scale: a showdown in the Astrodome, the nation’s first major domed stadium, which had opened in 1965. UCLA sports information director J.D. Morgan is credited with talking Wooden into it as a promotional vehicle for the sport. The game was slated for Jan. 20, 1968, and the platform was further elevated when independent station TVS bought the broadcast rights and put it on live television, with UCLA play-by-play man Dick Enberg on the call.

College basketball, a niche sport up to then, had itself a Game of the Century. And it lived up to all grandiose expectations, helping elevate the sport to a new level of national awareness. UCLA arrived undefeated and No. 1, on a 47-game winning streak. Houston arrived undefeated and No. 2. More than 52,000 spectators came to watch in person, enduring a fan-unfriendly court layout in the middle of the cavernous building.

Watch March Madness games live with fuboTV. Start your free trial today!

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated

“When we walked down that ramp to the floor for the pregame warm-up and heard over 50,000 people yelling for us,” Lewis told the Houston Chronicle at the time, “that was the most moving thing that’s ever happened to me in basketball.”

The Cougars won, 71–69, with Hayes (39 points, 15 rebounds and the game-winning free throws) dramatically outplaying Abdul-Jabbar (15 points). It turns out Abdul-Jabbar had been bothered by blurred vision and was wearing an eye patch in the days leading up to the game, with Wooden afterward alluding to still having the better player. After the game, Hayes showed some Houston hospitality by taking Abdul-Jabbar to a house party, where the two bonded. They would meet again in a collegiate rubber match a couple of months later in the Final Four.

The Cougars rolled in undefeated, but troubled. Point guard George Reynolds was declared ineligible shortly before the tournament due to insufficient credit hours at a junior college before enrolling at Houston. And the Bruins were more than ready to avenge their only loss since 1966.

Wooden was not going to let Hayes beat him a second time; he and assistant coach Jerry Norman devised a diamond-and-one defense to cover Hayes at all times with at least one and often two defenders. Houston ran into early foul trouble. And Abdul-Jabbar returned to dominant form, recording 19 points and 18 rebounds to Hayes’s 10 and five in a blowout Bruins victory.

“No basketball team in the world could have beaten UCLA this evening,” Lewis said afterward. UCLA would roll past North Carolina the next day to win the national title, then five more in succession. Hayes would be the first pick in the 1968 NBA draft, while Abdul-Jabbar would be the first pick a year later.

Today, Hayes will not concede that the better team won that rubber match. “I think we had a team that played the whole year a certain way, and then all of a sudden that team wasn’t there,” he says, citing Reynolds’s ineligibility and the Cougars’ foul trouble.

The end of the Hayes era foreshadowed more heartburn to come, but the program was launched, and its potential displayed.

“We were the first Blacks to be recruited here,” Hayes says. “We were the first Blacks to get on the varsity, to put it all together and start to win here. [Hakeem] Olajuwon and those games came, Otis Birdsong came, all these players came—but we were the first. We were very fortunate to come first.”

The year was 1988. The place was an airport bar in some remote outpost on the Continental Basketball Association playoff trail. Maybe Rapid City, S.D., Reid Gettys says. He’s not sure.

Anyway, Gettys and fellow Albany Patroons guard Sidney Lowe were sitting in that bar, eating cheeseburgers, waiting with their teammates for a late-night flight. ESPN was on the TV. Gettys looked up at the screen and froze. There was the Dereck Whittenburg air ball. And there was the Lorenzo Charles dunk. And there went Jim Valvano sprinting around the court, celebrating a massive upset that ended on the strangest buzzer beater to decide a national title.

It was the greatest moment in NC State history and the worst moment in Houston history. That path to the title was blocked by a fluke, a no-hope shot that dropped into the right hands at the right second to keep the Cougars from a title again.

Lowe played for the winning team in that 1983 championship game, and Gettys played for the losing team. They’d been Albany teammates all season and never said a word about that game. Now, here it was, five years after the fact, confronting them.

“I’m thinking, Don’t look at him. Just do not look at him,” Gettys says. “I finally do, and that jerk had reached into his bag and pulled out his national championship ring and put it on his finger. I just shook my head and started laughing.”

There was no laughing that night in Albuquerque, where a seemingly certain title had eluded the folk heroes who constituted Phi Slama Jama. A dazzling collection of athletic talent that included two future NBA Hall of Famers (Clyde Drexler and Olajuwon), Houston was 25–2 and ranked No. 1 heading into the NCAA tournament. NC State needed an improbable ACC tourney run just to make the field.

The Cougars rolled into Albuquerque thinking—like everyone else—that the national championship would be decided in their semifinal game against No. 2 Louisville. Both teams were high-flying and fearless, confident they could beat the other at its own game.

Andy Hayt/Sports Illustrated

“All we heard and all we read was that [the Cardinals] liked to run and play up tempo,” recalls Gettys, Houston’s all-time assists leader. “We were like, ‘We’re going to show them up tempo.’ We couldn’t believe it, because nobody played that way against us. Then it was game on, and it was awesome.”

A dazzling midair symphony ensued, with both teams attacking at a breathless pace—which, at the altitude of Albuquerque, became the literal case for Louisville. Eventually, the Cardinals wilted, and the Cougars kept throwing down dunks in a 94–81 victory. NC State, meanwhile, continued its unimpressive, survive-and-advance march by beating fellow underdog Georgia.

A huge underdog, Valvano schemed up a deliberate attack that relied on Lowe and Whittenburg taking the air out of the ball as much as possible on offense. In a game that smudged Lewis’s legacy, Houston played right into it.

Slowed and frustrated, and a bit spent from the track meet two days before, the Cougars never could get their vaunted fast break rolling in a sustained fashion. The pressure mounted, and the belief grew for NC State. Holding for a final shot, the Wolfpack botched the possession and left Whittenburg no choice but to heave the ball at the basket from about 35 feet out. It fell short.

The Cougars watched, stunned and flat-footed, as freshman Charles rose to grab the prayer and deposit it in the basket before the buzzer sounded for a 54–52 win.

“From a pure athletic perspective, it was as crushing a defeat and the biggest punch in the gut I’ve ever had,” Gettys says. “I clearly remember, before even going in the locker room, I sat on a staircase by myself in the arena. And right there, I felt a divine peace and comfort come over me. I had a moment to realize what an incredible blessing it was to be part of such an incredible team.”

Phi Slama Jama came back the following season, reconstituted for another Final Four run. Drexler was gone but Olajuwon was ascendant, and Houston went into the NCAA tournament ranked No. 5 and carrying a No. 2 seed. Three wins brought them to the Final Four in Seattle against an underdog Virginia team that was overachieving after the departure of center Ralph Sampson. Houston handled the Cavaliers, only to find the title path blocked by the dominant center of the 1980s, Patrick Ewing, and Georgetown. The Hoyas powered their way to an 84–75 victory, avenging their own heartbreaking title loss in ’82 and leaving Houston unfulfilled again.

“It’s a shame we didn’t win one with Phi Slama Jama,” says Houston billionaire Tilman Fertitta, a former Houston student and longtime fan whose name is on the newly refurbished arena. “There’s no doubt they were the best team of their time.”

Four Final Fours between Big E and Phi Slama Jama, four painful losses. Three of them came against all-time-great centers, one on an all-time fluke play. With Houston, it’s always something.

Greg Nelson/Sports Illustrated

In 2021, that something was Baylor. Kelvin Sampson’s biggest triumph to date was leading Houston back to the Final Four in that weird COVID-19 bubble tournament in Indianapolis. The problem is what the Cougars encountered in the national semifinals—a Baylor team that, in retrospect, is one of the more dominant men’s champions of the 21st century.

“We weren’t going to beat Baylor,” Sampson says, sitting in his office. “If we played them 10 times, they’d probably win nine.”

He pauses.

“This year I don’t see a Baylor.”

This year Houston has about as good a chance as anyone in the field, if it can avoid that final-step roadblock. Naturally, one complication already has arisen: a groin injury in the American Athletic Conference tournament last week to leading scorer and first-team All-American guard Marcus Sasser. We’ll see Thursday, when Houston opens the tournament in Birmingham, whether Sasser can go, and, if so, how effective he is.

But this Houston team didn’t get to be 31–3 by folding in the face of a little adversity. There has been too much dogged, incremental progress over the years for that. When Sampson arrived in 2014—having rinsed his image as an NBA assistant after NCAA sanctions at both Oklahoma and Indiana—he brought the spitfire attitude a dormant power needed.

“This was always part of the vision—playing in front of packed arenas,” Sampson said on the court after beating Wichita, a league championship net around his neck and a championship hat backward on his head, a 67-year-old going on 19 in that joyous moment. “When I got here, they didn’t understand that. They couldn’t see beyond where they were.

“Mindset-wise, we were probably closer to a Conference USA school than American Athletic Conference. We didn’t spend money. We didn’t invest. All we were pretty good at was firing coaches. Well, they weren’t going to fire me, not without making a commitment. If they didn’t make a commitment, fine, I’d go somewhere else.”

They made the commitment—Fertitta especially—pouring the money into a complete remake of the gloomy old Hofheinz Pavilion. (Gettys, who has worked for years as the Cougars’ radio analyst, recalls being able to individually count the number of fans at games in Hofheinz during the worst of times. One game he counted 56.) A modern practice facility was built as well, the Guy V. Lewis Development Center, a nice ode to the coach who elevated the program and came so close to winning it all so many times.

“We were never going to be competitive if we didn’t do that—first the practice facility, then the arena,” Fertitta says. Those infrastructure additions kept Sampson in the fold, and kept Houston from backsliding the way it did in the 1990s and early 2000s.

“We had a succession of coaches try to rebuild teams,” Gettys says. “Kelvin came in and rebuilt the program. It takes a special kid and a special mental toughness to play for him. You can’t teach a kid who isn’t tough to be tough, but you can teach a tough kid to be a basketball player.”

Sampson and his son, Kellen, who bears the unmistakable signs of being a rising star coach and his father’s inevitable successor, have recruited the fertile areas of Texas and Louisiana, often identifying players a notch lower in the rankings but a notch higher in competitive mindset. The results speak for themselves.

“This is validation for all the times you defended the culture when it wasn’t popular, when you had to make hard decisions on evals on recruits,” Kellen Sampson says. “The hard decisions have worked.”

Bob Levey/Getty Images

What they sold recruits on was what they sold the fans—put on your hard hat and join the grind. It works well in this city.

“I don’t know what else to call it,” athletic director Chris Pezman says of the program’s identity. “Just grit. Just, ‘F-U, I’m going to beat your ass.’ I mean, that’s just what they are.

“Look, we are a blue-collar town. Houston is a lot of awesome things, but we’re not Dallas. This isn’t, I’m rolling in with my popped collar or anything like that. There are oil refineries a few miles that way. This is, ‘I’ve got a pickup truck and I’m gonna beat your ass if you come at me.’ The city responds to that.”

How would Houston respond to having the Coogs in the Final Four right here? That would take the “For the City” slogan to an entirely new level. What if the alma mater of Hayes, Drexler and Olajuwon finally wins it all—at home—with a roster that has six Texans but no future NBA Hall of Famers?

The confluence of story lines—the long-worked-for conference upgrade to the Big 12 in the summer, Houston grad and CBS broadcasting legend Jim Nantz calling his last Final Four—is so tantalizing that Sampson and others at the school almost reflexively shun it. There is too much work to do to get there, too many things that can go wrong and have tended to go wrong historically for the Cougars, often on the final step.

“It’s like the perfect script,” Pezman says. “It’s come together. It’s hard to talk about it because it’s a lot. Where we’ve been, there’s a lot of people that have a lot of scars, a lot of wounds about things that happened in the past. It’s kind of cool to reflect that we’ve got those scars, but at the same time you’ve got this really special moment. I’m trying to make sure everyone recognizes that and enjoys it, because momentum’s fickle, man.”