Donnie Walker, U.S. history teacher at Wheatley High School in the Houston Independent School District (HISD), has a family legacy at the school. His grandparents went to Wheatley. His great-aunt graduated from the same class as Barbara Jordan, the first southern Black woman to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. His father and mother met at Wheatley.

Since Walker joined Wheatley’s teaching staff in 2019, the school has been at the center of a political power play by the state that resulted in an announcement by the Texas Education Agency (TEA) last week that they are seizing control of the largest school district in Texas.

Since 2019, Wheatley High School teachers and administrators have weathered a pandemic, all while improving their students’ academic performance, receiving a C state accountability rating last year. HISD earned an overall B rating with a score higher than 611 other Texas districts, including Dallas.

Still, TEA cites Wheatley’s past failures to meet state standards as reason to disband HISD’s elected school board. By June 1, the agency plans to appoint a new board of managers and superintendent, which could remain in charge for two to six years.

“Since 2019, we’ve been doing a wonderful job at holding our students accountable, the community accountable, parents accountable. Unfortunately, politics come into play, and guess who’s at the forefront of the politics. The State of Texas, Governor [Greg] Abbott, they’re not going to look in the mirror and point the finger at themselves. We’re getting blamed for everything,” Walker said.

Walker said the school has had to address plenty of new challenges since the time his family attended, particularly challenges created by school privatization in the Fifth Ward community.

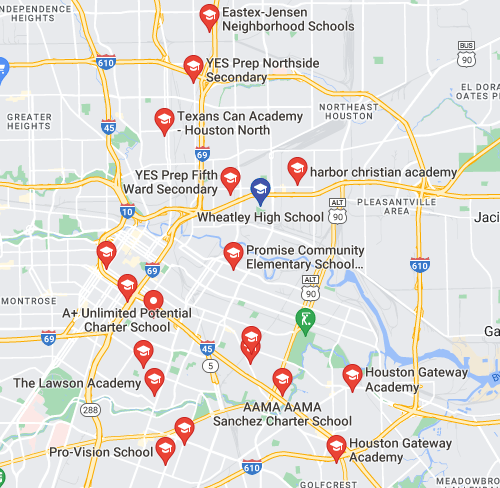

In 2011 Yes Prep Fifth Ward Secondary School, a charter institution, opened less than 5 miles from Wheatley. Since then, Wheatley has seen its enrollment decline. In 2017, the magnet school Mickey Leland College Preparatory Academy for Young Men also opened in the Fifth Ward.

“You could probably kick a ball in the backyard of Yes Prep and it’ll probably land in our football field,” Walker said.

While magnet schools are still run by public school districts, like charters, they are selective and can draw the highest-performing students away from neighborhood schools, along with the money allotted to those students. Meanwhile, local schools still need to pay for the same fixed costs of operating schools, such as building maintenance.

Unlike charter schools, as a neighborhood public school Wheatley is held accountable by federal laws to enroll and educate all students in the neighborhood, no matter their background. Wheatley educates more students receiving special education services, more students in the ESL program, and more students identified as at-risk than nearby private or charter schools.

“A lot of parents have this notion that Wheatley is already a school [with] issues, and what they do is place their children into these independent charter schools,” Walker said, thus siphoning off potential Wheatley students.

When students get kicked out of neighboring charter schools for disciplinary issues, Walker said, they often come to Wheatley, where teachers “rebuild them and prep them for life. We do all the things that these other schools failed to do for these students. They just get rid of them.”

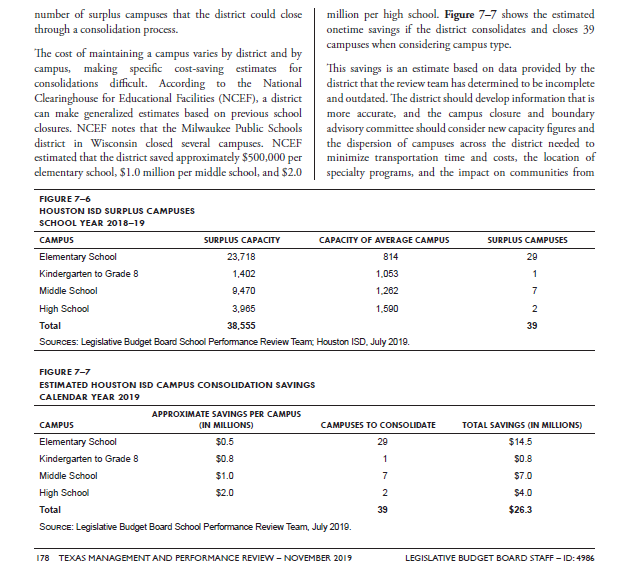

In 2019, more charter school districts than public school districts received an F accountability rating from the TEA. That year, HISD received an overall B rating, but TEA threatened the district with school closures and a state takeover. In a November 2019 audit of HISD, which the state released a few days after announcing its plans to take over the district, the state recommended closing or consolidating 39 HISD school campuses deemed “underutilized.” Like Wheatley, these schools have experienced declining enrollment due to proliferating charter schools in Houston’s low-income communities.

TEA Commissioner Mike Morath told Houston’s KHOU in a TV interview that he is not ordering any schools in the district to be closed, saying that the law stipulates a choice between state-appointed managers and school closures during a state takeover.

But community leaders are concerned that the state takeover will replace schools in low-income Black and brown communities with charter schools, which will not serve all students in the neighborhood. The Greater Houston Coalition of Justice, consisting of more than two dozen civil rights groups, filed a discrimination complaint with the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights last Friday.

TEA did not respond to the Observer’s inquiry into whether the agency plans to turn some HISD schools into charter schools.

In a press conference last Wednesday, Bishop James Dixon II, pastor of the Community of Faith Church and president of the Houston NAACP, questioned why the state is targeting HISD when other districts received lower accountability ratings.

“If academic achievement and financial management are the measures by which TEA determines whether a school is desirable, then what is it that the government hasn’t told the public that’s really driving this action?” Dixon said. “Why HISD? Does it have to do with the fact that we are majority brown and Black? Does it have to do with an economic agenda that is designed to close our schools and privatize our schools?”

Walker says that any plans to turn more schools into charters will only deepen existing inequalities in Houston’s communities.

“Charter schools have a right to turn their backs on kids and a part of the community. And if we start on that train and kick kids out and don’t cater to their academic needs, their social needs, these kids will be left behind in society,” Walker said.

He plans to stick around to make sure that doesn’t happen.

“Let’s prove everybody wrong and show that we are taking care of business. So the teachers at Wheatley are still pushing forward strongly to continue the legacy of doing positive things in our community, and continue the progress we’ve made since 2019.”