Welcome to SI Climate, our new ongoing series about how sports are adapting to—and affecting—our changing world.

Before the Friday-night lights of the fall, there is the weekday afternoon heat of the summer. Scorching, oppressive days of merciless, withering triple-digit temperatures that come accessorized with carpets of humidity. It makes for the kind of conditions that are singularly ill-suited for running around outdoors, never mind doing so while wearing an insulated helmet, and wreathed in a 20-pound carapace of pads.

But the coming of football season requires that teams start coordinating offenses, configuring defenses and defining their depth charts. The athletes need to start putting playbooks into practice and improving their conditioning.

You’ll see countless tableaus like the one that played out in mid-August on the practice field of Jackson State University in Jackson, Miss. Coaches’ whistles competed for sonic space with the psych-up music blasting from speakers. The stale air was perfumed by eau de athlete. Under a sky unencumbered by clouds, in conditions so hot it was as if the atmosphere had a fever, dozens of players lined up for various drills. Basted in sweat as he chugged a Gatorade, one player muttered, “It’s too dang hot,” less a nod to Ella Fitzgerald than a simple declaration of truth.

Courtesy of Phillip Laster Sr.

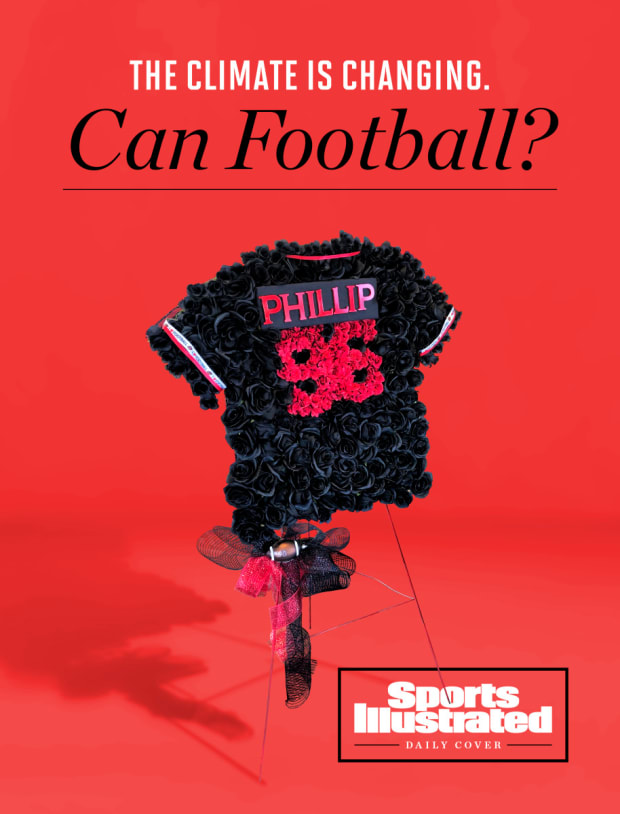

Fifteen or so miles to the east, a few weeks earlier, the same midsummer Mississippi heat had brought tragedy to the football program at Brandon High School, a large public school on the outskirts of Jackson. A football factory, Brandon was No. 4 in the MaxPreps preseason state rankings (and currently sits No. 1). On Aug. 1, during an afternoon preseason football workout, lineman Phillip Laster Jr. pushed his 300-pound body through a grueling session, as heat indexes exceeded 100°.

A rising senior, Laster—“Trey,” as everyone called him–had transferred as a junior and not played football last season. So he was particularly eager to impress his new coaches and make the team. Late in the session, Laster grew so fatigued he vomited multiple times. Laster’s family says it is still the fact-gathering stage but believes he was made to run extra laps as a penalty. (The school did not respond to requests for comment.)

Laster eventually passed out. Coaches administered CPR on the sidelines while waiting for an ambulance to arrive. A coach called Phillip Laster Sr. and implored him to get to the hospital immediately. The father didn’t arrive in time to see his son alive. Still in football gear, Trey Laster died that afternoon at age 17.

The number of football players who have died from heat has increased dramatically over the last decade, says Scott Anderson, the longtime head athletic trainer at Oklahoma and now president of the College Athletic Trainers Society. Laster was up to the 14th football player to suffer a heat-related death since 2020, according to tracking done by Anderson and Doug Casa, a professor of kinesiology at the University of Connecticut (there is no mandatory reporting on high school football deaths, so the pair cautions their numbers may be imprecise). All 14 players were linemen. Half were Black. While heat would seem to be an indiscriminate oppressor—come August, it is just as scalding on one side of town as the other—like so much else in the U.S., the impacts of climate change fall disproportionately.

While the Laster family awaits word on an official cause of death—as with many municipal offices in Jackson, the medical examiner’s has been slowed by the city’s water crisis—Trey’s father, Phillip, says he knows this: His son woke up that day looking forward to playing football and didn’t make it home. “This is rough,” Laster Sr. says. “We won’t get over it. We just get through it.”

Courtesy of Phillip Laster Sr.

Like an impact player altering the complexion of the game, climate change is leaving its considerable imprint on sports. Marathons and road races are routinely canceled on account of extreme and intense heat; the same reason the 2022 World Cup, usually a summer staple, starts in Qatar the same week we eat Thanksgiving turkey. In recent years, sports facilities have been charred by wildfires and turned into swimming pools by floods. In Louisiana, a high school sports field was flooded in ’20 by Hurricane Laura—but still fared better than the school gym, ravaged so badly that the basketball scorer’s table was found ten miles away. Hurricane Ian has wrought similar destruction in recent days.

Professional team owners know that if they want to build new stadiums—and get the public to pay for them—the venues had better come equipped with domes and retractable roofs, protecting both the athletes and fans from the elements. And it’s not just North America. It’s virtually everywhere; and it’s virtually every sport. In Port Elizabeth, South Africa, an outpost on the Indian Ocean, youth rugby coach Eric Songwiqi shook his head when he walked onto a local field on a scorching day last July. “People wouldn’t take their pets out in this heat,” he says. The same week, a world away in Massachusetts, more than three dozen runners in the Falmouth Road Race took ill with heatstroke, a leading cause of death in sports.

No sport, though, is more vulnerable to these perils of our ever-warming planet than football. The game may have largely pushed through the specter of head injuries and brain trauma, but now it lines up against another existential threat. Per a study published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, football players are eleven times more likely to get some kind of heat-related illness compared to other athletes. According to another study, from 2017 to ’21, the number of football players dying from exertional heatstroke, or EHS, has nearly doubled from the previous five-year period.

“There’s a lot working against [football],” says Andrew Grundstein, a professor at the University of Georgia, who specializes in heat vulnerability and human health. “[Players] wear protective equipment. Their body builds, especially the big lineman, make it harder for them to cool off. Their cardiovascular fitness, especially at the high school level, isn't the same as, say, someone doing cross-country. And it starts in August.”

The danger is compounded by the turf fields, often installed by schools to save water and money in equal measure. The issue: Often made from recycled tires, artificial turf heats quickly and intensely, running 60(!) degrees hotter than ambient air. As if practicing in 100° weather wasn’t enough of a safety hazard, the surface underfoot could be as hot as 160°.

In terms of climate change, August is the cruelest month, featuring the highest concentration of heat illness and heat-related deaths in the general population. And this peril is reflected in football. Eight of the 14 player deaths occurred in August. According to a study that tracked high school and college football fatalities from 1998 to 2018, in more than one-third of the cases, the player was subjected to exercise as punishment. In more than two-thirds of the cases, the players lived in the southeast.

And these trends aren’t likely to reverse anytime soon—not when nine of the 10 hottest years on record globally have occurred over the last decade. As Casa, the UConn professor, puts it: “I’d much rather have players training in January, February and March and have games in April, May and June—gradually, they’re going to get used to the heat. Yes, it’s going to get hotter [as the season progresses], but you’re not throwing them out there on Aug. 1, when they’ve been playing video games for six weeks.”

Apart from the “when,” football’s vulnerability also owes to the “where” and “why.” The sport, of course, is particularly popular in the Midwest and southeast, where summer conditions are often the most brutal. Then there are the logistics and (im)practicality of the sport. On hot days, the tennis team can practice indoors in air-conditioning; the baseball team can head to the indoor batting cages. The golf team can head to the driving range and cease walking around in the pounding sun. It’s the rare high school football program that has a dedicated indoor practice facility. It’s difficult to simulate 11-on-11 drills in the air-conditioned high school gym. It’s even harder if your school district can’t afford air-conditioning.

The culture of football doesn’t help, either. In a sector that prides itself on macho toughness—which includes perceptions of indifference to climate; note the bare arms in freezing weather—and has long considered “rub some dirt on it” to be sound medical advice, it’s easy to see why there might be a reluctance for young players in particular to complain about the conditions. “You compete in an environment that requires you to be tough, and it doesn’t necessarily require you to communicate your needs and feelings as an individual,” says Jessica Murfree, a professor at Texas A&M who studies sports ecology. “And it’s hard for people under the age of 18—trying to make the team or win a starting position—who are still developing and finding their voices, speaking on their behalf for their well-being.”

Remember Remember the Titans? Approached by a player seeking a water break, Coach Boone (Denzel Washington) responded memorably: “Water is for cowards. Water makes you weak. Water is for washing blood off that uniform, and you don’t get no blood on my uniform. Boy, you must be outside your mind.”

While the film takes place in the 1970s, Murfree says it taps into another factor that contributes to the danger of football: When coaches are unsympathetic to complaints about conditions, they often recall their own experiences. “Coaches say, We practiced in the dog days of summer. We survived; you will, too,” Murfree says. “But that fails to take into account how radically the climate has changed since then.”

Judy Griesedieck/Star Tribune/Getty Images

It was, ominously, on the first day of August 2001 that Korey Stringer died. A Pro Bowl offensive tackle for the Minnesota Vikings, Stringer, then 27, essentially overheated to death during training camp in Mankato, Minn. He passed out on the field, and after several hours of emergency treatment, his heart failed. The temperature of his 335-pound body reportedly reached 108.8°. (A core body temperature of 104° or higher is considered the main signifier of heatstroke.)

After her husband’s death, Kelci Stringer filed a $100 million wrongful death lawsuit against the Vikings. It was dismissed. She also sued the NFL, claiming the league had not done enough to ensure that equipment used by players protected them from injuries or deaths caused by heat-related illnesses.

For whatever Roger Goodell’s assorted missteps on various social issues, he was, by all accounts, early to realize the perils of playing football in extreme conditions. When he became NFL commissioner, he prioritized settling the lawsuit with Kelci Stringer. While most of the terms were—and remain—confidential, part of the settlement included funding to form the Korey Stringer Institute (KSI), dedicated to the prevention of sudden death in sports, with a focus on EHS.

In the course of the litigation, the Stringer family relied heavily on the expert testimony of Casa, the kinesiology professor. Casa devoted his life to researching heatstroke after he nearly died as a high school student in upstate New York in the 1980s, having collapsed while competing on a brutally hot day in a 10-kilometer track race. He credits savvy medical officials for saving his life by immediately cooling his body temperature.

After legal proceedings, Casa was named executive director of the KSI, housed on UConn’s campus. As the environment and climate change have played an increasingly outsized role in sports, the institute has played an increasingly prominent role as well. KSI has consulted with sporting events and organizations, ranging from cycling race organizers to the International Olympic Committee–for whom it set up heatstroke care for every venue at 2021's Games in Tokyo. But much of the institute’s work centers on football.

According to Casa, today, pro football is the least of his concerns. The NFL’s 32 teams take “maximum precautions” to protect against heat-related illness. They employ athletic trainers and nutritionists. They keep detailed data on players, measuring everything from sweat rates to wet bulb indexes. In the preseason camps, there are medical tents and ice-filled cold tubs on the sidelines. It’s much the same in college football. Even at Jackson State, which hardly has Power 5 facilities and funding, there are trainers on hand and managers handing out water bottles.

What does worry Casa: the more than 20,000 high school programs in the U.S. A full one-third of which lack medical trainers, according to the Athletic Training Location and Services (ATLAS) at KSI. For nearly two months between July and September, those in Jackson, Miss., including at Laster’s Brandon High, lacked even fresh, clean water from taps.

And, as COVID-19 vividly illustrates, global catastrophes are not equal-opportunity impactors. It is the poor and underprivileged that often bear the brunt. Football players impacted by climate change trace the same social cleavages. Schools that lack air-conditioning and trainers, literally feel the most heat.

“There’s a lot of work to be done to address environmental justice issues. Looking at it through sports is an eye-opener,” says Murfree. “There are going to be areas that are under-equipped and under-resourced to meet the needs. The difference is between having an athletic trainer for your youth sports teams; and having a coach who is also the trainer and the bus driver and also is having the players over for dinner. On those demographic lines, we know which [athletes] are more vulnerable.”

Short of radical reversal on climate change—and, equally unlikely, short of implementing Casa’s proposal of turning football into a winter and spring sport— there are still plenty of steps schools and programs can take to make the sport safer in the face of global warming.

• Acclimate. The biggest factor in exertional heatstroke among young athletes is a failure to adjust physically to the condition. Says Grundstein: “It takes the body some time to adjust to being able to deal with the heat. And the more time you’re in the heat, your body becomes more efficient in sweating and being able to cool off. So give players time to adjust to the heat.”

• Adjust to the weather. As the heat and humidity increase, so should rest breaks. (In professional South African rugby, there are now mandatory water breaks every 15 minutes.) As it gets hotter, players should refrain from practicing in pads. If it gets hotter still, coaches should call off the session. Likewise, schools and coaches can adjust times. On account of the heat, many state high school athletic associations—Mississippi included—have pushed practice times and Friday games to later in the day. Says Grundstein: “Morning or evening practices are going to be generally cooler than when high schools typically practice, right in the afternoon, which is typically one of the hottest times in the day.”

• Information is power. As heat becomes more extreme, data will become more valuable. Knowing athletes’ sweat rates and electrolyte intake will save lives.

• A trainer on every field. The National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research in North Carolina has a program aimed at dispatching athletic trainers specifically to underserved communities. Says Casa: “I just don’t buy it when people say they can’t afford an athletic trainer. They can afford eight football coaches and all the grooming of the field and all the staff, but you can’t have someone there three hours each day to save lives?”

• Take a position. Recognize that if heatstroke is a football problem, generally, it’s a lineman problem, specifically. Says Casa: “We still have football coaches in America doing training sessions that are the same for wide receivers, cornerbacks, running backs and lineman. They all do the same exact conditions sessions even though the stress and demands of activity for those players are dramatically different. Would you have a shot-putter and hammer thrower doing the same workout as a 100-meter sprinter? Never.”

It might be cold comfort in blistering heat, but treated properly, heat illness, unlike brain trauma, is entirely preventable and treatable. For instance, last summer’s Falmouth Road Race may have witnessed a staggering number of heat-afflicted runners, but because race officials were prepared, there were no fatalities. “The big difference between someone that dies from heatstroke and someone that goes home and has dinner with their family,” says Grundstein, “is if they get treated properly.”

Courtesy of Phillip Laster Sr.

And if the incentive to save lives isn’t enough to incite behavior change, there are market pressures. Specifically, the prospect of litigation. Outside Jackson, Miss., the family of Trey Laster grieves. Phillip Laster Sr. says that not a day goes by when he doesn’t cry. “We raised this kid right,” says Laster. “Trey was a warm, mild-mannered fellow; he displayed a lot of gentleman qualities. Yes, ma’am. No, ma’am. To know him was to love him.”

A former Mississippi high school football player, Phillip Laster worked with his son this summer “on little drills to get around those linemen; on sportsmanship; on strength and conditioning to make sure he could get out there and breathe.” He says he also warned his son about the climate. “The difference between now and when [I] played ball is that the heat is not the same. It will knock you out these days.”

Laster says he was particularly anguished when, on the first day of the school year, he had to return his son’s laptop to the school and passed by the funeral home on his way. “I’ll never get over it,” he says, “but I have to get through it. Part of what helps me is his character. I hear his voice, Dad, I’ve always known you as a strong man. You gotta continue to be that. None of this is your fault.”

By the end of August, the Laster family had engaged the services of noted civil rights lawyer Benjamin Crump, who represented the family of George Floyd. Laster stresses the family has yet to initiate legal action. But he notes the Mississippi High School Activities Association published a guide during this past summer repeating the fact that EHS is the leading preventable cause of death among young athletes. “We want to know why this wasn’t prevented in this case,” says Laster. “I never want to appear as an opportunist here; it’s not about any money. My child’s life is worth more than any dollar amount. … Awareness is what I want, because I don’t want anybody else to go through what I’ve been through.”

Sadly that’s unlikely. Asked about the future of football when pitted against rising temperatures and nature’s wrath, Casa sighs. “We know things are not going to get better,” he says. “It’s just a matter of how quickly it’s going to get worse.”