IF the Hunter River were to flow south and over the Newcastle shoreline, instead of curling around Stockton and heading east, its waters would just about splash into the Port of Newcastle's headquarters.

"I joke with people that the best job to have is with a port; we always get the best view," says Port of Newcastle CEO Craig Carmody, as the harbour fills the windows behind him.

That view from the Wharf Road offices also draws in the sheer scale of the organisation's responsibilities.

Port of Newcastle manages about 777 hectares of harbourside land, 21 berths, and the most crucial part of the waterway, from a shipping point of view: the channel.

As Craig Carmody puts it, "We are the ones who pull the land and the sea together".

And where the land and the sea meet sits a harbour city.

"We actually say we're in the heart of the city, and we are the heart of the city," Mr Carmody says.

What is at the heart of the city is privately owned. The NSW government sold a 98-year lease on the Port of Newcastle for $1.75 billion to a consortium comprising Hastings Funds Management and China Merchants in 2014.

The Port of Newcastle CEO says he is mindful the organisation is not so much the owner but a custodian of this enormous asset.

"Everything we do in this port, people have a view on," Mr Carmody says. "People walk along our foreshore, they run along it every morning, we have people who live near it, we have sometimes up to 10,000 workers who will come through the port in a given week.

"You can well imagine every time we make a decision, there's a lot of people in this city who have a say, or have a view, on what we've done, good or bad."

In this port, water and coal are synonymous. As the organisation's CEO, Craig Carmody oversees the world's largest coal port. More than 156 million tonnes of coal were exported through the port in 2021.

But the port can see shifts coming over the horizon in regard to fossil fuel usage and climate change.

Craig Carmody wants to get in first, before the impact of that rolls into the harbour, so he looks upon the organisation as a "start-up company, where we're really trying to change who we are".

The key to the change is diversifying the business, especially while the coal export market remains strong and the port can afford to move in another direction.

Craig Carmody points out the port is already about more than coal, with a broad range of products, from grains to fuels, coming in and out of the harbour. But he wants to see more of that, and in greater numbers, offering the slogan "50/50 by 2030".

"So we've said that by 2030, 50 per cent of our revenue would be from non-coal sources," Mr Carmody explains.

"Our plan is, and has always been, not, 'Oh well, as coal declines, we'll just replace it'. Our goal is, we want to build a business that is as strong as coal is today."

As we journey around the harbour, we will be looking more at Newcastle as a coal port, and the push for diversification, including the hopes for a container terminal on a parcel of the former BHP steelworks land.

But one enormous change to the harbour has already arrived at the waterfront, not far from the Port of Newcastle's head office.

JUST across the water from the Port of Newcastle base is a large sign on Dyke Point.

The sign is facing the harbour's entrance, and it is emblazoned with a message that is directed at those who are travelling into the port. Above the depiction by Indigenous artist Saretta Fielding of the river and the harbour is a word printed in block letters: WELCOME.

It seems that word has been embraced by those seeking a harbourside life along the Honeysuckle foreshore.

Thirty years ago, this stretch of the port wore the appearance of a harbour that was in a bad way. It looked unloved, and it was largely unpeopled. Everything about this land suggested its best days were in the past. Wharves were disused and decaying, and much of the waterfront seemed capable of growing nothing but weeds.

Yet the New South Wales Government saw Honeysuckle as a "growth centre". In 1992, the Honeysuckle Development Corporation was established, as the NSW Government Gazette indicates, "to promote, co-ordinate, manage and secure the orderly and economic development of the growth centre". Four kilometres of "surplus government railway and port-related land" along the harbour front were to be transformed.

In the eyes of many of those who live or visit there, what has grown in Honeysuckle is a vision splendid. The ugly duckling of the harbour has become a swan.

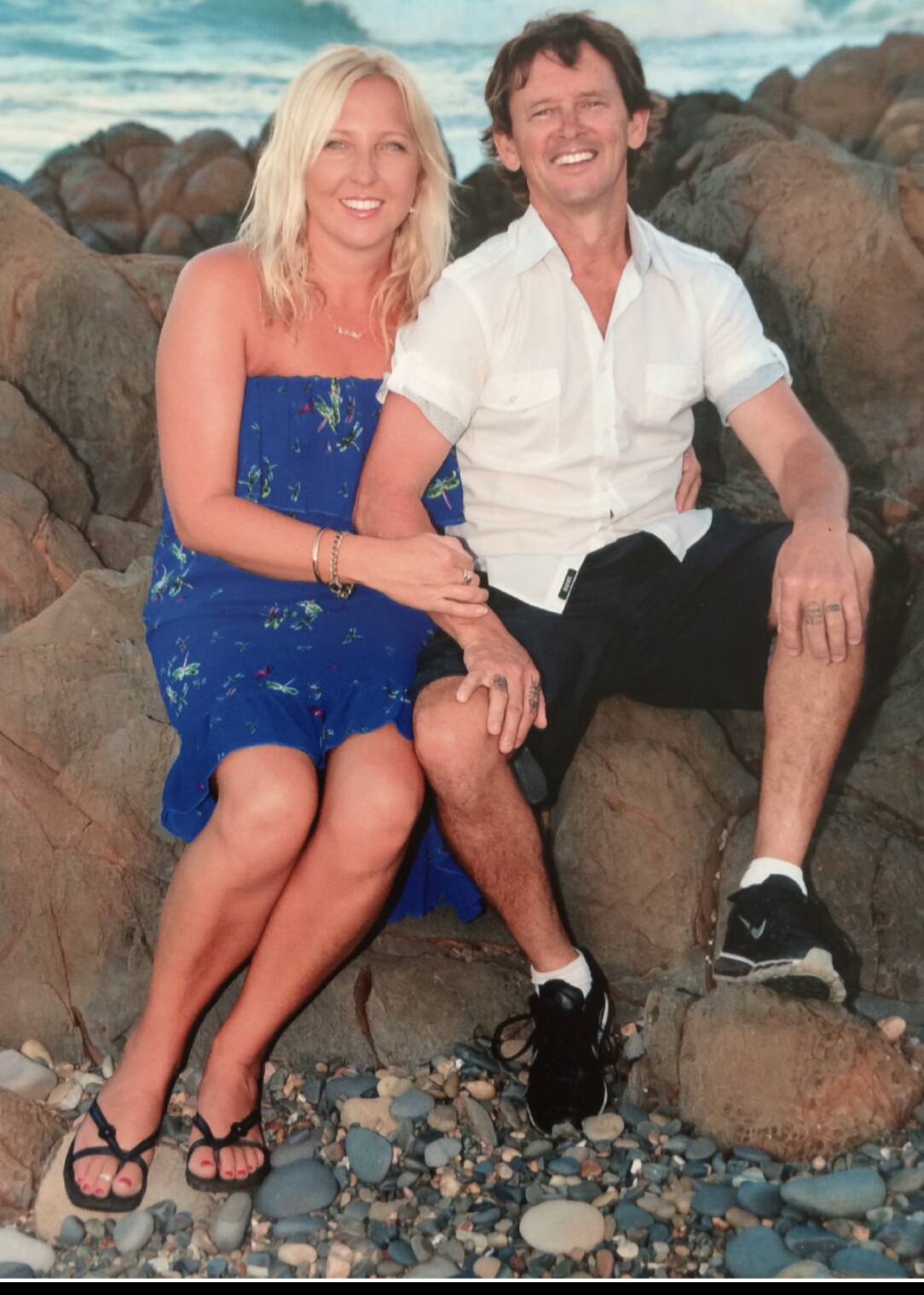

Michelle Robinson and her husband, former Newcastle councillor, Allan, moved into an apartment in the Lume complex about 18 months ago.

After raising their family at Warabrook, the Robinsons wanted to live by the water, but not by the beach. She didn't want to look at "just waves and the blue". So they moved into Honeysuckle.

"It's been better than we expected, because every single day there's something different to look at in the harbour," Michelle Robinson says.

"The idea of ships coming and going, the kayakers, stand up paddle boarders, the fishermen; there's always something to watch."

And something to hear, which doesn't please everyone.

Newcastle's Harbour Master Captain Vikas Bangia says since he stepped into the role in late 2020, he has received two complaints about horns.

"It's great to have people living so close to the harbour, but they need to respect we have some requirements for collision avoidance," Captain Bangia explains.

"There are fog horns. For me, as a ship's captain, it's music to the ears, a fog horn. It's not something the pilots or the ship masters are using as whims and fancies. It is actually for the safety of navigation within the harbour."

Michelle Robinson is surprised there have been complaints about the noises of a working harbour.

"It doesn't affect you, it doesn't wake you up, you know you're close to the water, so it's not annoying or irritating," she says.

However, with hundreds of units now on or near the Newcastle waterfront, it does raise the question of how residents and industry will get on as neighbours into the future.

Port of Newcastle CEO Craig Carmody says urban encroachment is happening in ports around the world, particularly as waterfronts are "gentrified". But he believes residents and industries live together harmoniously by the water. He says businesses are constantly looking at ways to reduce their impact on residents.

However, he doesn't believe having more people residing by the water in Newcastle means industries should move out or shift further up the river.

"The truth is we want a vibrant community, and a vibrant community requires jobs, it does require people making money, it requires people investing their money in our community," Mr Carmody says. "No disrespect to anybody here, but Newcastle is not a retirement village. And I don't think any of us want it to be that.

"For us here at the Port of Newcastle, we keep saying our number one goal is to create a future. What, so that you and I can retire and sit on our balcony in a nice quiet spot? Or is it so that the kids who are coming through have all the opportunities that you and I have had the luxury of having, as an Australian in the 21st century."

Michelle Robinson says she is happy having industries as neighbours. Some visitors to her Honeysuckle apartment have commented that it's a "shame" the view takes in the grain silos across the water at Carrington. She sees them differently.

"At night, when they're lit up, we like looking at them," she says. "It's fine having them there.

"I don't think they should push industry out, because it's the heart of the town."

Just over a kilometre away from the Robinsons' apartment is the City of Newcastle offices. From a terrace near the Lord Mayor's office, there is a view of the harbour towards Honeysuckle and over to Carrington.

But it is a view likely to shrink in the near future. The last remaining parcel of waterfront land at Honeysuckle is to be built on, with the NSW government's Hunter and Central Coast Development Corporation calling for expressions of interest in what can be done with that three-hectare parcel.

Lord Mayor Nuatali Nelmes has her own view on what should be built on that land.

"My firm view is that it needs to not be just residential apartments," Cr Nelmes says. "It needs to be activated space that is accessible but also provides access to jobs."

Councillor Nelmes grew up with harbour life making its way into the family's home in Brown Street, which tumbles from The Hill into the port.

"We could actually see the ships coming in and out from our windows in the house; it seemed completely normal," she recalls.

The lord mayor is pleased to see more people living in the city after many years of a declining population, but she also wants to see the waterfront accessible to everyone.

When the Honeysuckle Development Corporation was set up in 1992, its charter, in part, was to ensure the community had access to the harbour foreshores, and to create publicly owned and accessible places along the site.

Councillor Nelmes believes more could have been done in the design of Honeysuckle to achieve those goals.

"I personally would not have planned Honeysuckle the way that it has been planned," Cr Nelmes says.

"I would have planned it very differently. I would have actually had public domain, then the road and then development ... so you did have that access. You would have ended up with the same density, in terms of commercial and residential living; that density equation is exceptionally important to have people living and working in the city."

Once that final remaining land at the south-western end of the harbour is developed, it will join a line of residential and commercial complexes that, from Honeysuckle Drive, can feel like a constructed canyon, with just slivers of views through to the harbour. The compensation for those feeling drawn to the water is the foreshore promenade.

"The protection of the actual view for pedestrians, and that walkability around the edge of the harbour, we did fight hard to protect that," the Lord Mayor says.

Councillor Nelmes points out this is not council land, and Honeysuckle has been largely planned and approved through the NSW government. The planning of this area, she says, was done "in isolation to the rest of the city". But there have been efforts to have the city connected to the harbour.

"What I've spent a lot of time doing is trying to retrofit the city for that connection to actually occur," Cr Nelmes says. "It's not ideal, but it is much better than it used to be, with some connections from Hunter Street back through to the harbour areas."

Many of the new buildings by the water have sprouted on reclaimed land.

On a map from 1866, this area is marked as "Honeysuckle Point", and the shore's outline meanders around a peninsula. However, the demand for more shipping accommodation led to the foreshore being reshaped. Spoil was used to fill in the shoreline, straightening it out, in the early 1900s. This stretch came to be known as Lee Wharf.

This was the port's main cargo area from the early 20th century to the 1960s.

Everything from wool and timber to frozen meat were loaded on and off ships at Lee Wharf, with those cargoes often passing through the storage sheds squatting by the water.

A couple of the early Lee Wharf sheds have survived. One has been reimagined as the Honeysuckle Hotel.

The other, built more than a century ago, is currently empty, as it is being converted into a Hunter winery's cellar door in the city. That old shed may be overshadowed by the new developments, but it majestically holds its ground by the harbour, telling a story of the port's earlier days.

In recent years, this shed was a repository of the port's history, housing the city's maritime museum, before that was moved out in 2018 and mothballed in uncertainty.

Those passionate about Newcastle's maritime history have been pushing for a new home for the museum.

The most precious cargo to arrive in the port, contributing so much to the development and the maturing of this city, has been people.

In 1949, four years after World War Two finally ended, the Fairsea, the first ship carrying displaced people from Europe to Newcastle, tied up at Lee Wharf.

Over the next few years, more "migrant ships" would arrive, with the passengers stepping onto Australian soil, and into their new lives, here by Newcastle harbour.

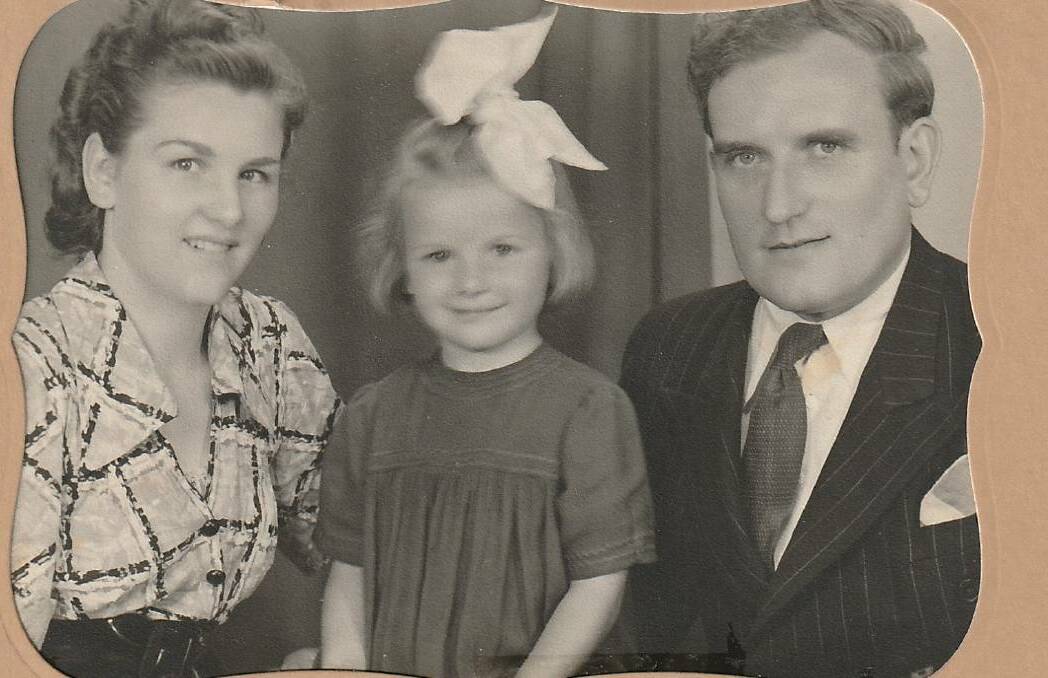

One of those passengers was Halina Paczynski.

"I arrived in this harbour on the 18th of December, 1950, with my parents, as a four and a half year old," says Ms Paczynski.

"The ship that I arrived on was the SS Roma, and it brought 949 refugees and displaced persons from Germany. We left Bremerhaven, and we came here to start a new life in Australia."

The daughter of a Polish father and German mother, Halina Paczynski can't remember what she was thinking and feeling as a little girl, when she arrived on the other side of the world in summer. But she knows the significance of the weatherboard shed on the wharf.

"We all went off the ship into the building and were processed in there, in this very building," she explains. "Collected our luggage and went out the other side."

Outside the shed were rail lines, as Honeysuckle was etched with tracks for trains transporting cargoes shipped to and from Newcastle.

Waiting on the tracks was a train to take the new arrivals to the migrant camp at Greta. So Halina Paczynski's Australian life would begin further up the valley, far from the harbour. But the harbour called her back.

As a young woman, she would ride on the ferry to Stockton and back while eating a hamburger - "It was very relaxing and soothing" - and she would regularly return to Lee Wharf, to think about where she was, and where she had come from. For water can do that; it connects you to other places, other times.

"This was always a place I used to visit and walk down the wharf and look at the ships and imagine what it must have been like for Mum and Dad," Ms Paczynski recalls. "And it always gave me some sort of connection to Europe. I don't know why. It's just how I feel."

The harbour has enriched Halina Paczynski's life. But those arriving in the harbour from distant lands enriched the life of Newcastle, providing a diversity of cultures and a much-needed workforce for the industries.

"I don't think that Newcastle would be as large or as rich a place, if it weren't for the harbour," she says.

Which is why Halina Paczynski considers it "disgraceful" that the maritime museum was removed from the Lee Wharf building.

Outside the museum was a Welcome Wall, etched with the names of those who had arrived by ship, including the Paczynski family's, celebrating the port's history of immigration. But the commemorative wall was dismantled, and the plaques went into storage.

"It's a loss of not only my past, but it's a loss of the past of this city," she says.

But Halina Paczynski has her memories. The surroundings may have changed, but she delights in coming to the old Lee Wharf and looking at the historic shed.

"This is like visiting an aunt's house or a grandparent's place," she says, before gazing once more at the harbour and the waters that carried her here.

"This is a spiritual home."

Read more:

"Harbour Lives with Scott Bevan - Part One": Entering the Port.

"Harbour Lives with Scott Bevan - Part Two: From the 'Dog Beach' to Scratchleys.