Music pumps; lights pulsate; two sweaty bodies sway together, touching, breathing in each other’s scent.

A male body framed by downlight restlessly shifts between stances and gestures. He undresses. The intensity of music, movement and light builds while his naked body performs a spiritual act of transformation, of unbecoming.

Two bodies lie onstage among a pile of upended chairs, human and plastic legs intertwined.

These are fleeting glimpses of my experience at Homo Pentecostus. Moments that have stuck themselves to my body, my memory, challenging me to make sense of them.

Homo Pentecostus is a collaboration between actor-dancer-writer Joel Bray, performer Peter Paltos and theatre-maker Emma Valente.

These three are powerhouses of Melbourne theatre, each working across mainstage and independent sectors, and all identifiably queer. Weaving together personal experiences of growing up queer in religious institutions, the performance takes shape as a two-hander for Bray and Paltos.

Chasing a spiritual experience

The show consists of interwoven conversations, storytelling, vignette, dance and song. It moves fluidly across modes that are presentational, representational and didactic. At times the performers interact with the audience.

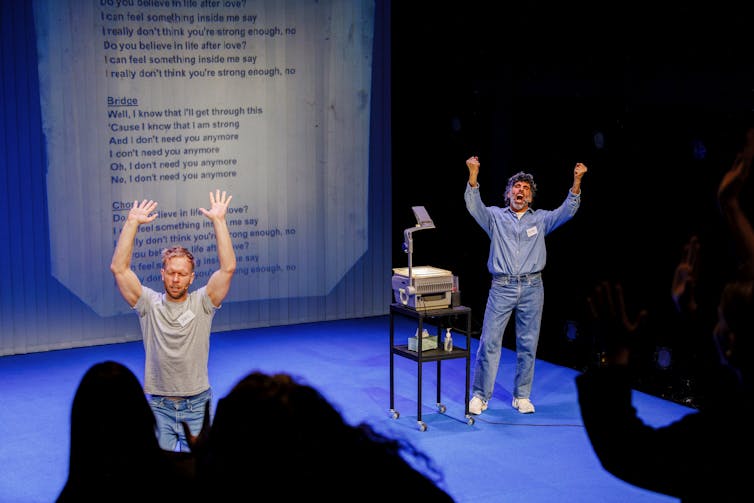

Together we sing Cher’s late-’90s classic, Believe. Bray teaches us dance moves designed to open ourselves to the Holy Spirit while Paltos helps us with lyrics. It’s hard in this moment to ignore the human desire for spiritual connection. Collectively belting out Cher and physically moving together in such a way promises to deliver on such a potential.

The elusiveness of spiritual transformation is a theme thrumming through the show. Seeing mum in full glamour for the first time (a “chanteuse”), the first gay kiss as a teenager, and a months-long sexcapade with a Swiss: each stands in for spiritual encounters Bray and Paltos, as queer people, have failed to experience through religious rituals and blessings.

Gay bars – or queer clubs – emerge thematically through sound, light and movement, implicitly signalling the euphoric and utopic possibilities of these spaces as queer spiritual institutions.

Ancestry and intimacy

Bray, a Wiradjuri man, reflects openly on his past in the Pentecostal church. For Bray, the church is synonymous with colonisation and the patriarchy.

Paltos’ Armenian and Greek ancestry and history in Christian churches are similarly laid bare. Stories shared are personal, often deeply painful, with layers of ambivalence sitting underneath. With an unhalting delivery, Paltos tells us his childhood church considered being gay comparable to paedophilia, so as a child he was afraid he was a paedophile.

Such moments are like staring into the sun: it is unbearable not to wince and look away.

Bray and Paltos are delightful together. Their chemistry is the beating heart of the show. They hold each other in a uniquely intimate, care-giving and sensual manner. There is a gentleness in their physical language, proximity and touch, and they constantly lean into and onto each other.

At points the energy becomes sexual, especially with Bray being fully naked for much of the show, but the intimacy and delicacy of their onstage relationship is most striking.

A queer Pentecostal aesthetic

In his artist’s note for the production, Bray describes how making the show led to a self-discovery:

Pentecostal aesthetics, and ways of being, moving and communicating are coded into my very DNA.

Bray’s notion of Pentecostal aesthetics is interesting given how it overlaps with queer aesthetics in this production.

Set and costume designer Kate Davis offers a giant wall of vertical blinds. The stage otherwise contains 60 white, stackable plastic chairs and an overhead projector on a movable stand. At points the blinds serve as a screen for projected images, which are controlled and scribbled over by Paltos to create striking visual effects.

The DIY look and feel of the work, Bray’s naked body in Christian iconographic poses, the abstract setting of a church or community hall, the desire for visibility and community acceptance, and the fusing of “low” art forms with theatre and dance styles in the production’s staging all nudge towards an aesthetic that is simultaneously queer and Pentecostal.

Lighting by Katie Sfetkidis punctuates the stage with colour, vibrancy and movement, siloing and spotlighting action. Marco Cher-Gibard’s music and sound design runs a gamut from camp pop to atmospheric background tracks to nature sounds. The theatrical elements work in harmony; the effect is exuberant, joyful and at times meditative.

Navigating the emotional wreckage of their lives (made physical by the upending and piling of chairs), Bray and Paltos find and hold onto one another. In all, the show gives rise to ideas of queer intimacies, kinship and the human need for connection.

If you’re in need of a queerly spiritual intervention, or more simply looking for a show that will stay with you, I urge you to experience the rise of Homo Pentecostus.

Homo Pentecostus is at Malthouse Theatre, Melbourne, until May 25.

Jonathan Graffam does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.