Plans for the Hauraki Gulf have attracted a range of criticisms, with environmentalists cautioning they don’t go far enough and others upset at rule exceptions for tangata whenua

After a successful email deluge aimed at stopping Auckland Council from adopting Māori wards, Hobson’s Pledge has turned its attention to new marine reserve legislation that retains customary seafood collection rights for tangata whenua.

As leader of the right-wing lobby group, former National Party leader Don Brash has been calling on his followers to make email submissions on the forthcoming Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana Marine Protection Bill.

READ MORE:

* Moment of truth for Waiheke marine reserve

* Whales are the canary in the coal mine for the Hauraki Gulf

The group is asking supporters to submit a copy-pasted message opposing the right of Māori groups to continue to use parts of the Hauraki Gulf that will otherwise become protected areas.

Submissions on the bill, which was put together by Minister of Conservation Willow-Jean Prime, ended on Wednesday at midnight.

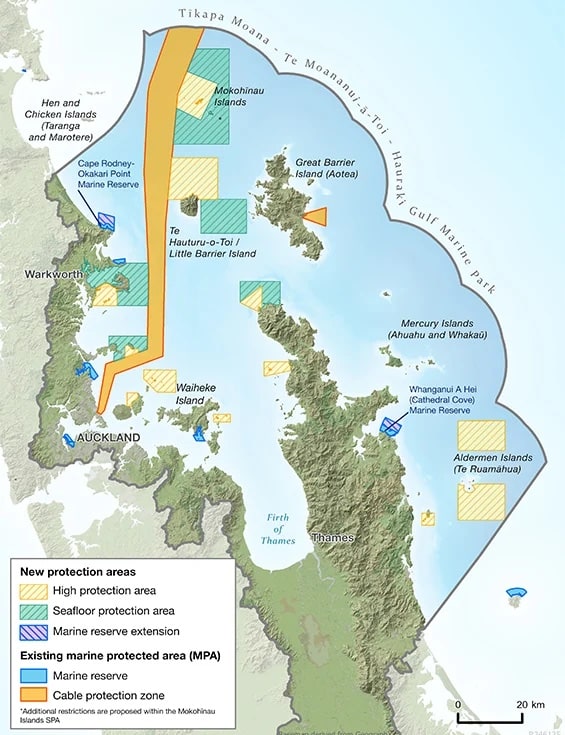

The bill would see extensions to the Cape Rodney – Okakari Point Marine Reserve at Goat Island and the Whanganui A Hei Marine Reserve at Cathedral Cove, and bring in five new seafloor protection areas where trawling is prohibited and 12 new high protection areas.

Fishing, dredging, landing of aircraft and the removal of sand would be controlled in the 12 protected areas, which would be located at:

- Little Barrier Island / Te Hauturu-o-Toi

- Slipper Island / Whakahau

- Motukawao Islands

- Rotoroa Island

- Rangitoto and Motutapu

- Cape Collie

- Mokohīnau Islands

- Aldermen Islands / Te Ruamāhua (north)

- Aldermen Islands / Te Ruamāhua (south)

- Kawau Bay

- Tiritiri Matangi

- Ōtata / Noises Island

But though fishing would be forbidden to most in these areas, it would still be allowed for customary fishing – defined in the Fisheries Act 1996 as “customary food gathering by Māori … to the extent that such food gathering is neither commercial in any way nor for pecuniary gain or trade”.

When the details of the bill were announced in August, Prime said this distinction allows for tangata whenua to exercise their kaitiakitanga or guardianship of this natural resource.

“The Bill also supports tangata whenua in their role as kaitiaki and in exercising rangatiratanga and acknowledges the cultural value of Tīkapa Moana,” she said.

It’s a move authored with 1992 Treaty of Waitangi fisheries claims in mind. That act obligates elected members to develop policy that recognises the use and management practices of Māori in the exercise of non-commercial fishing rights and make allowances for customary food gathering to continue.

Prime said this particular bill had been “shaped by the aspirations of tangata whenua and local communities around Auckland, the Gulf Islands and the Coromandel.”

It’s this particular section of the bill that seems to have stuck in the throat of Brash and co.

The email campaign asks submitters to voice support for the extension of the two marine reserves but oppose the protected areas that would preserve those customary rights for tangata whenua.

The email accuses the bill of fostering “more division, resentment and hostility in our country”.

“While ‘customary rights’ are claimed as an entitlement by tangata whenua, it would be appropriate for them to lead by example for the benefit of future generations, instead of prohibiting takes by everyone but themselves,” the template email reads.

The mass email campaign is one Hobson’s Pledge has dipped its toes in recently, with thousands of emails sent to Auckland councillors before last week’s vote on Māori wards.

Brash thanked his supporters for their help in reaching out to councillors, saying “your significant contribution has played a crucial role in influencing Auckland councillors’ decisions to vote against the inclusion of Māori seats”.

Māori wards were narrowly rejected, with most of the opposing councillors voicing a desire to revisit the idea in a few years.

But it’s unclear whether full inboxes swayed opinion.

Waitākere councillor Shane Henderson said last week that the Hobson’s Pledge campaign had merely had the effect of making it hard for him to hear from constituents living in flood-damaged properties as their correspondence vanished into the sea of identical lobbying emails.

Councillor Angela Dalton said it was a tactic used more frequently by groups such as the Taxpayers' Union, who had used mass email floods to lobby for cost cuts in this year’s Budget.

But race relations is the favourite itch to scratch for Hobson’s Pledge, and so these email campaigns seem singularly motivated by changes that would enshrine representation or rights for Māori groups.

However, even if there are thousands of emails in opposition, the government will still need to honour the legislation which directs policy to act in accordance with the Treaty of Waitangi, which promised continued rangatiratanga over natural taonga.

Even in the ecological space, the bill hasn’t been able to please everybody – non-profit organisation LegaSea also encouraged people to submit on the bill, which it said didn’t go far enough to protect the Marine Park.

“It's not good enough to only focus on protecting a few areas, which will push more intensive fishing into a smaller area,” the group wrote to followers. “Displacing fishing effort is not acceptable, especially if you live in or value that new, heavily fished area.”

Forest & Bird and Greenpeace have been critical of the bill restricting trawling to specific corridors rather than a full-scale ban.

Meanwhile, Waiheke-based conservation group Friends of the Hauraki Gulf had its own misgivings.

The group has been advocating for a 2350 hectare reserve to the northwest of Waiheke Island, which would almost double the protected area within the gulf.

Many other protected areas within the gulf are found directly up against the coastline, but this large reserve would occupy the important transitional zone between the waters of the inner and outer gulf.

It’s the point where the seafloor drops away to a deeper ecosystem where rare species, such as packhorse crayfish, can be found.

But though there has been strong support from gulf residents and local Māori, getting a clear answer back from central government has been a slow process.

The Department of Conservation told the group in July last year that it would give the Minister of Conservation its advice in November. That was then delayed to July this year.

But now the department has pushed the date out again to February 2024.

The group is calling on the government to include the proposed reserve as a part of the bill, which would still only establish less than half of a percent of the total Hauraki Gulf as protected.

“Including extensions to just two marine reserves, means the Bill will provide only a minimal increase in totally protected areas,” the group’s submission reads.

“While the two marine reserve extensions will certainly expand the current fully protected areas from the current paltry 0.3 percent of the Hauraki Gulf – but only by a couple of decimal points or so.”

The group is chaired by Waitematā and Hauraki Gulf councillor Mike Lee, whose group has some common ground with Hobson’s Pledge when it comes to customary fishing rights in high protection areas as well.

The group’s submission said exceptions to prohibited fishing “compromises the stated ‘marine protection’ purpose of the Bill”.

However, the group states it does not oppose customary fishing areas, but would rather see them called as such as opposed to high protection areas.

“We acknowledge the Fisheries Act provisions that must be complied with, but we suggest the combining of two different objectives, customary fishing and marine protection, will likely mean difficulties and complications in the administration and monitoring of these provisions – and the effectiveness of high protection areas themselves.”

Speaking in council yesterday, Mayor Wayne Brown wanted to know how protected areas – yellow on the map – would be signposted in real life.

"If I'm out there in my boat, how the hell do I know I'm not accidentally fishing in [the areas]," he said. "The water's not yellow when I'm out there."

He questioned the seemingly arbitrary shapes that appeared on the map and said the plan would confuse people.

"They all watch TV so much when you watch the racing of those yachts around there and you see it's all... marked out," he said. "But it isn't actually like that when you go out there and have a look, it just looks like water to me … and if you're trying to look after your Māori interests out there in your canoe, mate, you haven't got a bloody chance."

Auckland Council manager of environmental strategy Dave Allen said the areas had been scientifically determined, but said central government needed to resource making the public aware of how it works.

"In terms of how you'd actually identify those … the marine charts will be updated … your GPS plotter will be automatically updated," he said. "It does look kind of confusing when you look at it on one A3, but to be honest this is just one layer of lines, there are plenty of other lines we are not presenting to you here that relate to some of the fisheries management and controls."

Brown was sceptical of the right-angled shapes that appeared on the page.

"I have never seen anything in nature as a neat rectangle, they tend to be odd shapes, so there's a sort of bureaucratic that's interfered with common sense here, what is the disease that we are fixing in Wellington?" he said. "The aims are wonderful, but I'm absolutely sure that the fish don't know that they are in a rectangle."

From here a parliamentary select committee will prepare a report on the bill to present to the house in February next year.

Presumably taking submissions into account, the report will then be able to recommend changes to the bill before its second reading.