The Reserve Bank has called a halt to interest rate rises. But pre-GFC pauses were followed by renewed hikes.

It came as no great surprise to anyone when the Reserve Bank paused its aggressive interest rate hikes last week, leaving the official cash rate at 5.5 percent. But history suggests that isn't necessarily the end of the matter. The Reserve Bank has paused and un-paused before – and may do so again.

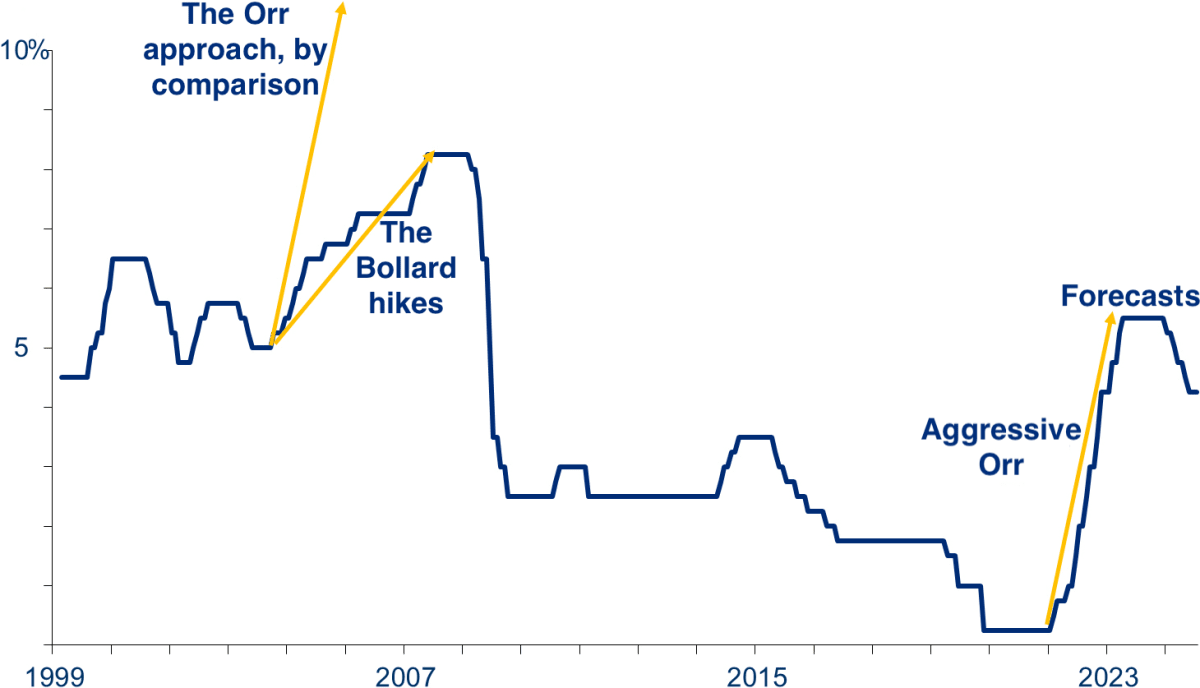

As the graph below shows, under Alan Bollard, who served as governor of the Reserve Bank between 2002 and 2012, official cash rate (OCR) rises stopped and started multiple times, and at higher rates than we have now.

The official cash rate was frozen at 6.75 percent for seven months in 2005 before rising twice to reach 7.25 percent. It then sat there for more than a year before jumping up to 8.25 percent over several months in early to mid-2007.

Interest rates stayed around that level until the global financial crisis took hold in New Zealand. As financial markets crashed, business and consumer confidence tanked and people stopped investing and spending.

Interest rates went down, and down, as central banks around the world tried to stimulate economic activity. And they stayed low for the decade or so between the GFC and the Covid-19 pandemic, when an unexpected boom had the Reserve Bank scrambling to slow the economy down again.

READ MORE: * Reserve Bank’s meat is retailers’ poison * Forced sale concerns for 43,000 mortgage holders * More mortgage payments – forever

In May, the Reserve Bank's Monetary Policy Committee was split 5:2 on whether to raise the OCR again, but in the end chose to lift it 25 basis points to 5.5 percent, but at the same time indicating rate hikes were likely over for the time being – hence the 'no change' announcement last week.

"Everyone is over-confident that the Reserve Bank is done just because they've said they think they probably are." – Sharon Zollner, ANZ

So are we likely to see the same sort of stop-start OCR movements we saw in the Bollard era?

BNZ head of research Stephen Toplis says Bollard and current governor Adrian Orr have taken very different approaches, with Orr opting for quicker more radical OCR hikes to “try and knock inflation on its head”.

Orr and his panel definitely considered the Bollard hikes in making their decision, he says.

“If you look at the Bollard rate hike process it carried on for four years and if you read between the lines, the current Reserve Bank has said if we've got to make a correction, we don't want it lingering for that long.

“We'd like to get it over and done with quickly.”

The lag between rate hikes being implemented and being felt by the population can take as long as 18 months, and the full effects could be harder to account for with a speedy Orr approach compared to a slower Bollard strategy.

While the Reserve Bank has committed to a pause, giving the history of rate hike pauses and plays, can homeowners who’ve seen their mortgage payments treble be confident the OCR has peaked for this cycle?

Toplis suspects tightening in the labour market in 2007 surprised Bollard and the uptick in inflation probably also came as a surprise, which meant the RBNZ had to had to go one step further.

“Equally that could happen to this administration.

“I think homeowners can be confident the Reserve Bank believes that if the world evolves in the manner it thinks it will evolve, there will be no need for further rate increases.”

ANZ chief economist Sharon Zollner is less sure. “I think everyone is over-confident the Reserve Bank is done just because they've said they think they probably are.

“You just have to look at the last few years to see how difficult economic forecasting is, so I think the confidence intervals are often wider than is generally acknowledged.”

Zollner says getting inflation under control will be a non-linear process.

“There's some low hanging fruit and quick progress, but then the progress might stall.

“There are two questions: how much damage has the Reserve Bank already done to growth and the labour market; and how much is necessary? Both of those things are very uncertain.”

Zollner expects the economy could well prove more resilient than the Reserve Bank is expecting because of demand coming from net migration and fiscal policies. And that means those last couple of percentage points to get inflation to within the Bank's 1-3 percent target range could take a bit more work – and maybe rate hikes.