They sometimes got help on that journey through the Underground Railroad, an informal network with locations in Chicago and throughout Illinois that offered shelter, protection, food, clothing and advice to freedom seekers.

Chicago was in the midst of transforming from a frontier town to a bustling but still small city throughout the mid-1800s. Between 1833 and 1850, Chicago’s population increased from roughly 300 to just under 30,000.

Enslaved people from the South came north to Chicago during this period seeking freedom. Chicago was a city of refuge before 1850. And free Black people played a major role in supporting these freedom seekers as they arrived or passed through the city.

Then, Congress’ passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 fundamentally altered Chicago’s place for those seeking freedom.

Between 1850 and 1865, when slavery was abolished, the city’s role became more complicated than it previously had been. It was still a place where Black people seeking freedom settled and put down roots — getting involved in the growing economy, building social institutions and leading abolitionist organizing.

But, because of new dangers that arose with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law, the city frequently was seen not as a destination at that point but as a stop along the way to surer safety in Canada.

Chicago before Fugitive Slave Law (1833-1850)

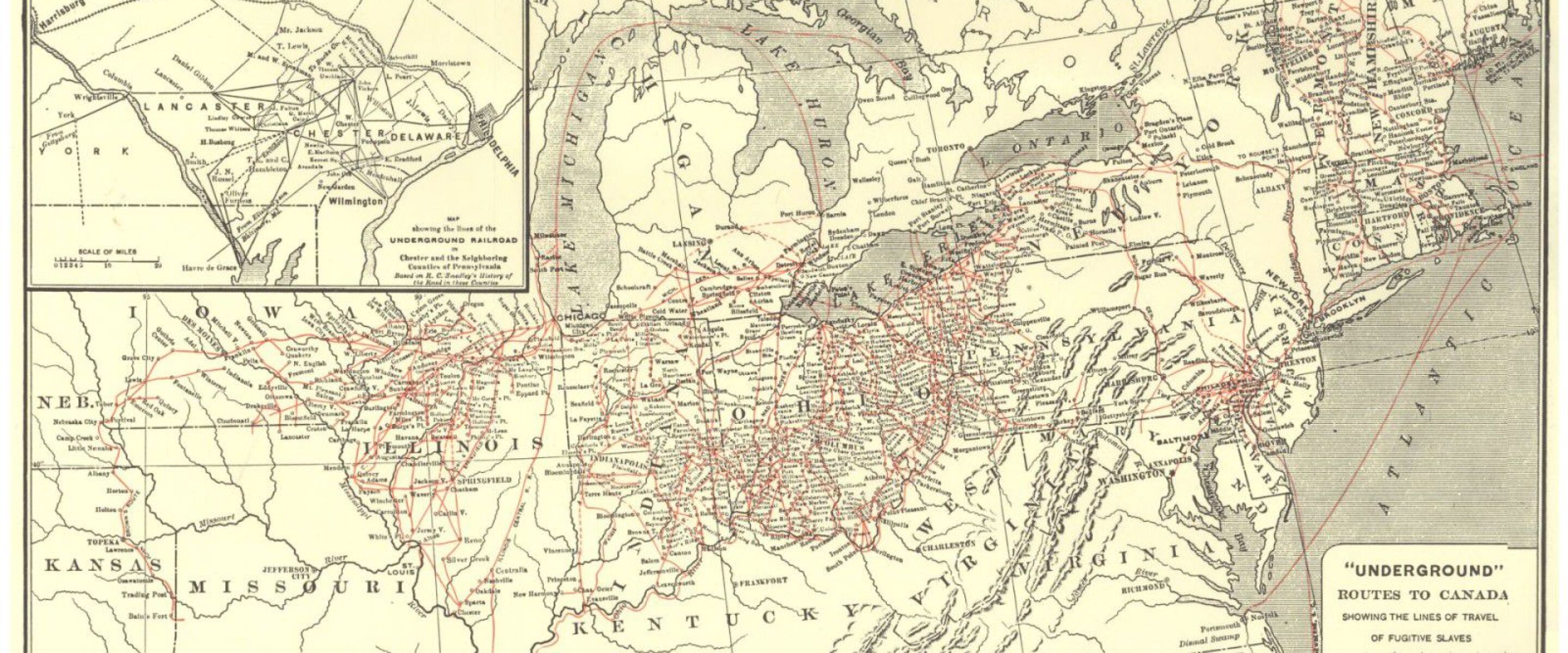

Many freedom seekers reached Chicago by traveling north along the Mississippi River. Following the river provided a helpful guide and also made it more difficult for trackers to find them. The water could wash away footprints and cover scents.

The people who lived along the Mississippi River in the 1830s were more diverse than those in many parts of the United States. Many were white, but there also were free and enslaved Black people and Indigenous people. That diversity made it less clear who was enslaved and who was not, and thus easier for a freedom seeker to pass unnoticed.

According to Larry McClellan, a professor emeritus of sociology and community studies at Governors State University in University Park: “One of the reasons Chicago became such an important goal for people was because of this Mississippi River Valley culture. Word was passed very easily. And so, very early on, word reached all the way to New Orleans that one of the ways to freedom was to get yourself to Chicago.

“And the word gets to Black people living on plantations. And they know if they can get to the Mississippi River Valley and head north, they can find their way to freedom.”

Before 1850, historians say, Chicago was a relatively safe destination.

“It was really quite a safe place for Underground Railroad freedom seekers to put down roots and be able to benefit from their labor,” historian and author Glennette Tilley Turner says.

Some continued from Chicago to Canada, where slavery had been outlawed since 1834. Generally, though, Chicago was considered a city of refuge for Black people during this time, as described by the late historian Lawrence D. Reddick.

Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

The Fugitive Slave Act that Congress passed in September 1850 was part of a package of laws designed to avoid a civil war between pro-slavery and anti-slavery states. The Civil War began little more than a decade later.

The Fugitive Slave Law gave enslavers the right to re-enslave freedom seekers who had escaped and gone north to free states.

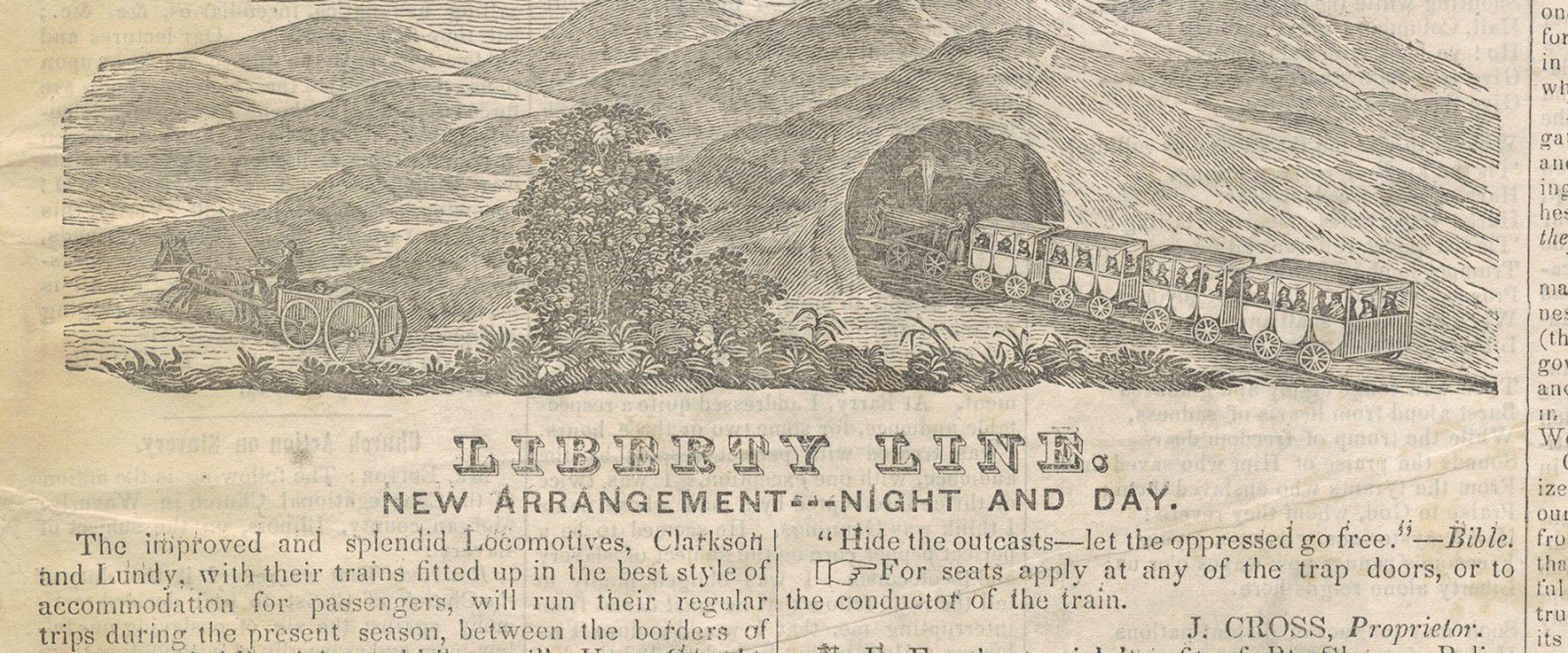

It also made helping freedom seekers illegal and punishable by fines or imprisonment. Enslavers often worked with law enforcement, posting newspaper ads offering a reward for freedom seekers’ capture and relying on sheriffs to arrest and return formerly enslaved people.

Chicago post-Fugitive Slave Law (1850-1865)

The Fugitive Slave Law actually made Chicago a more dangerous place for freedom seekers.

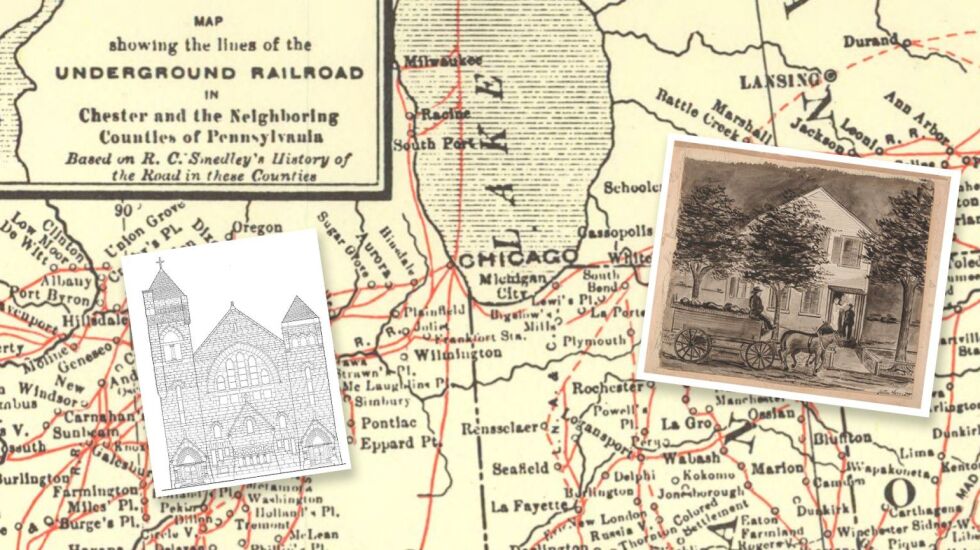

Previously, the Underground Railroad helped people get to Chicago. After 1850, the Underground Railroad helped people pass through Chicago to Canada.

Many Black people who had found freedom in Chicago and even bought property fled, leaving behind their homes and belongings, according to historian Christopher Robert Reed.

In his book “Black Chicago’s First Century,” Reed quoted an unnamed “Oldtimer” whose account of life in Chicago as an early Black settler was published by the Illinois Record in the late 1890s. According to the “Oldtimer,” after the Fugitive Slave Act was passed, “The kidnapping of the fugitive slaves by slave owners, assisted by some of the low whites and the officers of the city, was the chief conversation among our people.”

The Western Citizen, an abolitionist newspaper in Chicago, sometimes published accounts of attempts to re-enslave Black Chicagoans — as well as ways anti-slavery citizens could resist the new law.

Historians have identified a handful of places freedom seekers passing through Chicago sought refuge, among them the Tremont House Hotel, the home of abolitionist John Jones and Quinn Chapel A.M.E. Church — all within a few blocks of one another near what today is downtown Chicago.

Quinn Chapel is perhaps the best-known Underground Railroad stop in Chicago. In “Black Chicago’s First Century,” Reed wrote of four women congregants of the church — Emma Jane Atkinson, Joanna Hall, “Aunt Charlotte” and a fourth whose name was likely Mary Richardson Jones — who served as conductors on the Underground Railroad and harbored freedom seekers in their homes.

According to genealogist and author Tony Burroughs, who has researched the Underground Railroad, there are undoubtedly many places in the city where freedom seekers found shelter or food that weren’t regular Underground Railroad stops and about which we know very little.

“When freedom seekers traveled through free states, it was not uncommon for them to sleep in barns or wherever they could on the way north,” Burroughs says. “They sometimes even went inside houses and asked for food if they thought it was safe.”

A patchwork history

Larry McClellan says many 20th century accounts of the Underground Railroad in Chicago were overblown.

“The big problem we have with this is that all the time, people are identifying Underground Railroad sites that simply are not,” McClellan says. “In the 1870s and ’80s, after the Civil War, it was a very prestigious thing to have been involved in the movement for abolition.”

Historians and researchers including McClellan, Reed, Burroughs, Glennette Tilley Turner and Karen Lewis have searched for these records and pieced together fragments of this history.

Part of why it’s so difficult to find records of Underground Railroad activity in Chicago is the work was dangerous. For freedom seekers, the stakes were incredibly high. People who were caught seeking freedom could be re-enslaved.

And those who helped them faced fines and incarceration. So there was good reason not to keep records in the traditional sense.

As a result, the historical record skews toward those who had power: enslavers’ ads in newspapers offering rewards for returned freedom seekers, bills for “services rendered” by law enforcement for the arrest of a formerly enslaved person.

So while we have glimpses of the people who risked their lives to seek freedom — and those who helped them — many of their stories remain untold.

Contributing: Justine Tobiasz