You can’t talk about Jeff Buckley without talking about his death, so let’s get that out of the way first. He drowned at age 30 while swimming alone in the Wolf River.

Buckley’s recordings would be haunting even if he were still alive, but his life being cut so short adds an extra layer of emotion to his already intensely emotional music. The tragedy is only heightened by the fact that Jeff’s father Tim Buckley was a well-respected art-folk singer who also died very young. Tim sings and writes beautifully, but he still sounds like a regular human. Jeff sounds like an alien, or a being from another dimension.

As befits Jeff Buckley’s strangeness, Grace is a strange album. It’s nominally “alternative rock”, but Buckley doesn’t sing or write like a typical 90s alt-rocker, and he includes a couple of songs that are conspicuously not rock at all. One is Corpus Christi Carol, a 500-year-old traditional tune arranged by Benjamin Britten. The other is Lilac Wine. It’s only 75 years old, but it sounds even less like alt-rock than Corpus Christi Carol does.

Musical theatre composer James Shelton wrote Lilac Wine in 1950. He was inspired by Ronald Firbank’s novel Sorrow in Sunlight, in which a character named Miami Mouth is walking around at a party offering people "a light, lilac wine, sweet and heady". Before you go looking to read it, I have to warn you that the book was written by a white British guy in 1925 about Black characters, that Miami’s dialogue is entirely in fake dialect, and that the n-word is used frequently. So maybe just stick to the song.

By the way, lilac wine is a real thing. (Here’s how to make your own.) It frankly sounds gross, but it does make for a vivid lyrical metaphor.

Versions

Jeff Buckley learned Lilac Wine from Nina Simone. Her arrangement is sparse, consisting only of her piano and Lisle Atkinson’s upright bass.

Lilac Wine has been recorded by many other people, almost all of them women. Eartha Kitt’s version, backed by a full orchestra, set the tone in 1956.

Elkie Brooks had a European hit with her soft-rock-plus-strings version in 1978.

Miley Cyrus doesn’t have Jeff Buckley’s subtlety or Nina Simone’s gravitas, but she has her own charm.

The song doesn’t need to be sung in order to work. Here’s Brad Mehldau’s epic solo piano version.

The most divergent take on the tune is DropxLife’s J-Dilla-esque hip-hop instrumental, built around pitched-up samples of Jeff Buckley.

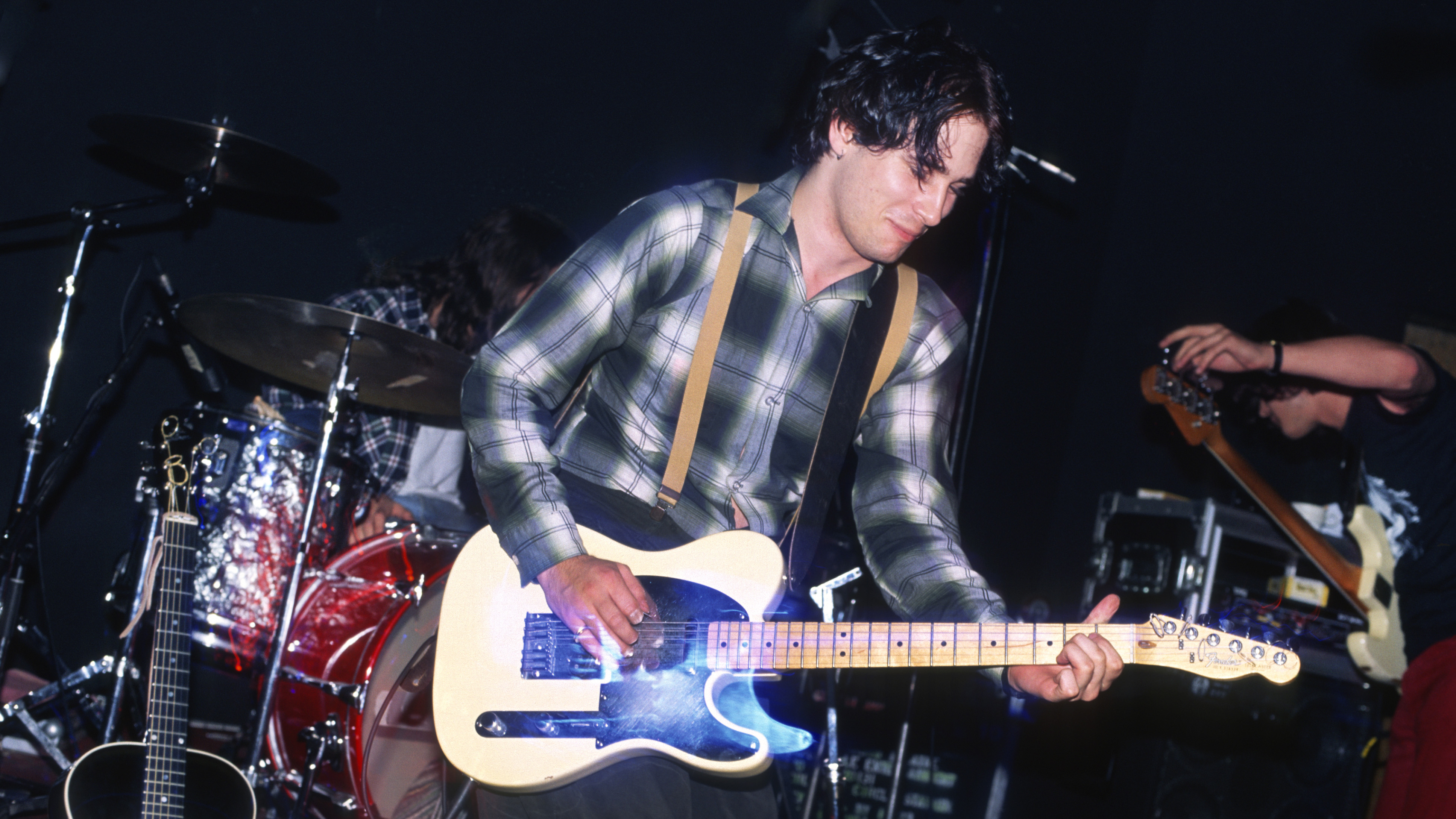

Jeff Buckley’s arrangement is aesthetically more aligned with Nina Simone’s sparseness than with Eartha Kitt’s or Elkie Brooks’ lush grandiosity. Aside from his voice and chorus-soaked guitar, the only other sounds on the track are Mick Grøndahl’s bass and Matt Johnson’s drums.

Grace was produced by Andy Wallace. He has an extraordinarily eclectic list of credits, ranging from Afrika Bambaataa to Limp Bizkit to Phish to Kelly Clarkson. For Lilac Wine, you might think that all he needed to do was set the mics and hit record, but he also crafted a delicate mix with a wide dynamic range and just the right amount of reverb.

In this video, Wallace explains how he layered several different reverbs together to create Buckley’s guitar sound on his recording of Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah.

Rubato

Aside from Buckley’s otherworldly voice, the most striking feature of Lilac Wine is the rhythm. Most of the song is in tempo rubato, an Italian term meaning “stolen time”. The idea is that you “steal” time from some places (speed up) and put it back elsewhere (slow down). Buckley paces himself however he sees fit in the moment, and the other musicians have to follow his timing. This gives an unsteadiness to the music that matches the theme of unsteadiness in the lyrics.

Rubato is the predominant rhythmic feel in Western European classical music. The conductor’s job is to lead the ensemble through constant stretchy, expressive tempo changes. By contrast, rock hardly ever uses rubato except as a special effect in intros and endings. Rock bands don’t have conductors because they don’t need them; someone counts off at the beginning, and then everyone just tries to keep the tempo as steady as possible.

In the pre-rock era, musical theatre ballads were often performed with rubato, and there are a couple of rubato jazz ballads like Nature Boy and Lush Life too. By singing Lilac Wine, Buckley is calling back to a time when popular song was more closely related to opera than to the Afro-diasporic grooves underpinning rock, dance and hip-hop.

There are a lot of differences between classical music and Anglo-American popular styles like rock–structures and forms, harmonic and melodic conventions, instrumentation, recording techniques–but I think musical time is the most important stylistic distinction. Ben Neill argues that the presence or absence of a beat is the single main factor dividing “art” from “popular” music.

The classical world considers metronomic time to be dull, mechanistic and unmusical

The classical world considers metronomic time to be dull, mechanistic and unmusical. In 1920, Constantin von Sternberg described a hypothetical accompanist playing in metronomic time as “a poor blockhead who hammers away in strict time without yielding to the singer who, in sheer despair, must renounce all artistic expression.”

If you are a lover of rock, jazz, or country, you know that there is plenty of space for artistic expression within the confines of a steady beat: swing, pushing and pulling, and various other microrhythmic subtleties. But it is also true that allowing for moment-to-moment tempo changes adds a new expressive parameter to the music. Jeff Buckley’s time feel is highly elastic even over a typical rock beat; you can see why he would be drawn to a rubato ballad.

Chords

Given all the rubato, it’s very difficult to map out a bars-and-beats chart of Lilac Wine. Instead, I’ll convey the placement of the chords by writing along with the lyrics. Listen to the recording for timing. The tune begins with its only verse, all within the key of G minor:

(Gm) I lost myself on a cool, damp night

(Eb) I gave myself in that misty light

(Am7b5) Was hypnotized by a strange delight

(D7) Under a lilac (Gm) tree

The same chords repeat for the second half of the verse. Then there’s the prechorus, which begins with a shift into C major before returning to G minor:

(B°7) When I think more than I (C) want to think

I (Cm) do things I never should (Gm) do

(B°7) I drink much more than I (C) ought to drink

Be- (Cm) cause it brings me back (D7sus4) you (D7)

Then there’s a two-bar interlude, played in tempo, at an achingly slow 58 beats per minute. This interlude is a bar each of G and G7, a surprise pivot from G minor to G major. This leads into the chorus, also in steady time throughout:

(G) Lilac wine (G7) (C) is sweet and (D7) heady

(G) Like my love, (G7) (C) lilac wine, (Dm7) (G7)

I (C) feel un- (Dm7) steady (G7), like my (C) love

The postchorus is back in tempo rubato. The Eb chord represents a brief shift back to G minor, before returning to G major on the Am7 and D7 chords.

(Eb)Listen to me, I cannot see (D7) clearly, isn't that she coming to me?

(Am7) Nearly (D7) here

The chorus and postchorus repeat, and then the final chorus ends Cm6, D7, G, blending G minor and G major to the end.

Gender

I’ve talked about every aspect of Lilac Wine except Jeff Buckley’s singing, but that’s probably the main thing that drew you to the song in the first place, so let’s get into it. You could write an entire gender studies dissertation on Buckley, and people have. I’ll limit myself to referencing one academic source: the book Oh Boy! : Masculinities and Popular Music, which includes a chapter by Shana Goldin-Perschbacher entitled “‘Not With You But Of You’ - ‘Unbearable Intimacy’ And Jeff Buckley’s Transgendered Vocality”.

Goldin-Perschbacher is not arguing that Buckley was trans or queer; he was a straight cis man. However, Buckley’s singing and song choices defy the standard norms of cis masculinity in rock, especially 90s alt-rock, and his fans have certainly noticed.

Buckley had a four-octave range, but he usually sang (and spoke) in a distinctly female-sounding register. He sounds tender and vulnerable, and he seems to be frequently overwhelmed by his emotions. Lilac Wine is one of several songs in his repertoire that are closely associated with female singers, and Buckley doesn’t change the pronouns. He even went so far as to call himself a “male chanteuse”.

Jeff Buckley guitarist Michael Tighe: “That dude could have done anything; he could have gone into opera, or more classical-type stuff”

Jeff Buckley is hardly the first male singer in rock history to sing in a female register, or to emote uninhibitedly. However, while Robert Plant or Axl Rose might sing high and even scream, they don’t really ever sound feminine. The closest equivalent I can think of to Buckley’s androgyny is Prince, but unlike Prince, Buckley didn’t visually present as femme; he was only gender-nonconforming in his singing.

I don’t know anyone who is neutral on Jeff Buckley; people either love him or hate him. Goldin-Perschbacher attributes that to the shocking intimacy he creates with the listener: “Buckley’s performance aesthetic could seem, to some, too private for public performance. The relationship between Buckley and his listeners was so intense that it felt metaphorically, if not literally, sexual, in terms of privacy, pleasure, and self-discovery.”

His fans love him because he draws their own hidden feelings to the surface. And presumably his anti-fans experience the same thing, they just don’t want those feelings intruded upon. By singing a 1950s torch song in the 1990s, Buckley now seems to exist outside of eras and genres entirely. I'm sure that people will still be listening to him for a long time into the future.