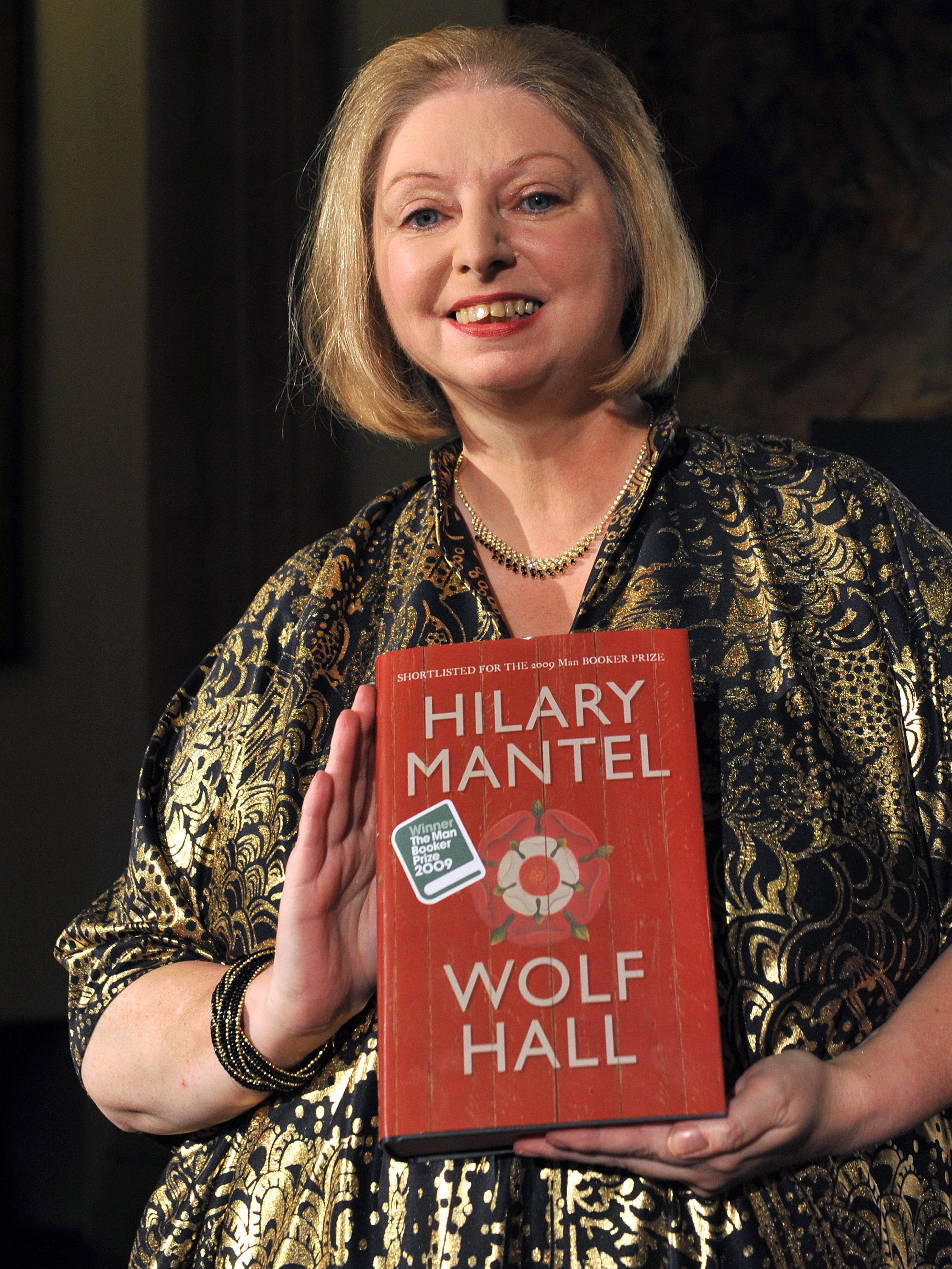

Hilary Mantel, a British author best known for her Wolf Hall trilogy, a series of bestselling novels set amid the political turmoil of 16th-century England, for which she twice won the Man Booker Prize, one of the world’s most prestigious literary awards, has died aged 70.

Mantel had written critically praised historical and contemporary novels to little commercial notice before she became a literary phenomenon in 2009 with Wolf Hall and two subsequent novels, Bring Up the Bodies (2012) and The Mirror and the Light (2020). The books, based on the life of Thomas Cromwell, a key minister to King Henry VIII, were set in an epoch awash with royal intrigue, religious upheaval, ruthless political machination and the brutal treatment of women.

In Cromwell, she found a character who was alternately resourceful, sympathetic and cunning. “Lock Cromwell in a deep dungeon in the morning,” Mantel wrote in Bring Up the Bodies, “and when you come back that night he’ll be sitting on a plush cushion eating larks’ tongues, and all the jailers will owe him money.”

Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies won the Man Booker Prize, making Mantel the first British writer – and the first woman – to win the honour twice. The Wolf Hall books have been adapted for a BBC miniseries and as plays produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company.

Reviewing Wolf Hall in The Atlantic, writer and critic Christopher Hitchens pronounced it “a historical novel of quite astonishing power ... The means by which Mantel grounds and anchors her action so convincingly in the time she describes, while drawing so easily upon the past and hinting so indirectly at the future, put her in the very first rank of historical novelists.”

Cromwell, a real-life figure with a mysterious, rough-hewed past, had been an adviser to Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, a Catholic cleric who had once been close to Henry VIII. Henry broke with the Catholic Church after it refused to grant him an annulment from Catherine of Aragon, the first of his six wives.

Wolsey was ousted, as the opportunistic Cromwell then helped guide Henry through a separation from the Catholic Church. Henry declared himself head of the Church of England, coinciding with the Protestant Reformation then occurring in northern Europe. Cromwell helped to arrange some of the king’s later marriages, as Henry hoped to have a male heir to the throne.

The three novels, totalling almost 2,000 pages, proceed through the rest of Henry’s ill-fated marriages – two of his wives were beheaded – and examine the relationships of Cromwell and others surrounding the all-powerful king.

Mantel, who struggled with poor health and was in pain for much of her life, wrote with an urgency and an awareness of human frailty that gave her novels an added sense of poignancy. She suggested that Henry VIII may have had osteomyelitis, a bone infection of the leg.

“Historians, and, I’m afraid, doctors,” she told The Guardian in 2020, “underestimate what chronic pain can do to sour the temper and wear away both the personality and the intellect.”

Mantel spent years writing her books, drawing on meticulous historical research. “I cannot describe to you what revulsion it inspires in me when people play around with the facts,” she told The New Yorker in 2012. “If I were to distort something just to make it more convenient or dramatic, I would feel I'd failed as a writer.”

Instead of a dry recitation of 500-year-old facts, her novels are told in the present tense with the hot breath of everyday life. The dialogue crackles with menace, irony and wit, women are vibrant characters, and people of all social classes are caught in the swirl of forces beyond their control.

Besides the high drama of the king and his court, Mantel chronicled other historical events, including a deadly plague, that echoed through time.

“The warm weather has brought sweating sickness to London,” she wrote in Wolf Hall, “and the city is emptying ... This plague came to us in the year 1485 ... Now every few years it fills the graveyards. It kills in a day. Merry at breakfast, they say: dead by noon.”

Mantel makes the plague personal by describing the symptoms of its victims, including Cromwell’s wife and two daughters.

“I’m very keen on the idea that a historical novel should be written pointing forward,” she said in 2009. “Remember that the people you are following didn't know the end of their own story. So they were going forward day by day, pushed and jostled by circumstances, doing the best they could, but walking in the dark, essentially.”

Hilary Mary Thompson was born 6 July 1952, in Glossop, Derbyshire. Her father was a clerk, and her mother had worked in a textile mill.

When Hilary was a child, her mother took up with a male boarder in their house, Jack Mantel, and her father left the family. Eventually, she, her mother and two younger siblings moved to Chelsea, London, with Mantel. The children took his last name, even though he and Hilary’s mother were not married.

“The story of my childhood is a complicated sentence that I’m always trying to finish, to finish and put behind me,” she wrote in Giving up the Ghost, her widely praised 2003 memoir that addressed her physical ailments and her loss of religious faith. “My childhood ended so, in the autumn of 1963; the past and the future equally obscured by the smoke from my mother’s burning boats.”

After attending Catholic school, Mantel enrolled at the London School of Economics, hoping to become a lawyer. She transferred to the University of Sheffield, graduating in 1973 and soon marrying a fellow student, Gerald McEwen. She then worked as a social worker and store clerk and battled debilitating headaches, leg pain and other unexplained ailments. Doctors could not diagnose a physical illness and prescribed antidepressants.

She accompanied her husband, a geologist, to Botswana in 1977, teaching English and working on a historical novel set in 18th-century France. A self-described obsessive reader, she also studied medical textbooks and concluded that she suffered from endometriosis, a painful gynaecological condition.

At 27, she had surgery that left her, in her words, “minus ovaries, womb, bits of bowel, bits of bladder. Minus a future, as far as having children was concerned.”

Mantel’s first novel was rejected by publishers, and when her endometriosis returned, she was treated with steroids, causing her to gain a great deal of weight. She and her husband divorced in 1981, then remarried a year later before moving to Saudi Arabia, where they lived until 1986.

While there, Mantel wrote a pair of novels set in northern England, Every Day Is Mother’s Day (1985) and Vacant Possession (1986), centring on a toxic mother-daughter relationship. In 1988, Mantel published Eight Months on Ghazzah Street, a novel based on her bleak life in Saudi Arabia, followed a year later by Fludd, about religious belief in a community in northern England in the 1950s.

During those years, Mantel wrote film reviews for the Spectator magazine in London and dozens of book reviews. Her earlier novel about the French Revolution, A Place of Greater Safety, finally appeared in 1992.

Despite chronic illness, she published three more novels in the 1990s, including the acclaimed The Giant, O’Brien (1998), based on the historic story of an Irish giant exhibited as a curiosity, whose death is exploited by a scheming doctor. Mantel adapted the novel for a BBC play.

Her final novel before the Wolf Hall trilogy was Beyond Black, a dark comedy touching on religion, clairvoyance and ghosts.

“Many of my novels, whatever their theme,” Mantel said, “have a supernatural tinge. Paranoia is their climate, the macabre is always lurking.”

Sometimes blunt and acerbic in her political views, Mantel was criticised in 2013 for describing Catherine, then Duchess of Cambridge, as a “shop-window mannequin, with no personality of her own”. A year later, Mantel published a short story, The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher, that led some politicians to call for an investigation. Mantel pointed out that the story was fictional and, in any case, the former prime minister was already dead.

In addition to her husband, Mantel’s survivors include a brother.

Mantel said her lifelong health problems led her to consider writing a form of release, a way of transcending her troubles.

“I have been so mauled by medical procedures,” she wrote in her memoir, “so sabotaged and made over, so thin and so fat that sometimes I feel that each morning it is necessary to write myself into being.”

Hilary Mantel, writer, born 6 July 1952, died 22 September 2022

© The Washington Post