Lining up for this year’s Leadville Trail 100 MTB, I underestimated the challenge ahead, convinced that science wouldn't apply to me. I arrived in Leadville on Thursday afternoon, just 36 hours before the race, which served as the third stop in the Life Time Grand Prix.

I hoped my body wouldn’t notice the sudden change in altitude. It didn’t take long for my body to recognize the sudden lack of oxygen, reminding me that the effects of altitude are very real.

Despite well-established literature on the impacts of high altitude on performance, I was confident that I wouldn’t be just another statistic. After all, I’m a well-trained athlete and have thrived in high-altitude races before, with past wins in Colorado at SBT GRVL, peaking at 8,476 ft (2,584m); The Rad Dirt Fest, peaking at 8,921 ft (2,719m); and Utah’s Crusher in the Tushar, peaking at 10,291 ft (3,137m).

How bad could a little less oxygen be in a race that never dips below 10,000 feet (3048m) with a peak of 12,600 feet (3840m)?

"How bad could an extra 5k feet be?" I thought, coming from Boulder, which is halfway to Leadville’s cruising altitude of 10,000 feet (3048m).

As it turns out, very bad.

I quickly learned that going from Boulder to Leadville is a bigger drop in effective oxygen rate than moving from Atlanta, Georgia, to Boulder, Colorado, a transition I made just over a month ago. But more on that in a bit.

Racing across the sky

As I climbed Powerline the day before the race to get a lay of the land, an ocular migraine - often triggered by high altitude - hit me hard. It wasn’t my first time experiencing this, so I knew the usual culprits: exercise, dehydration, stress and high altitude. When I started to see zigzagging patterns and floating lines in the rocks and trees, I braced for the severe headache that would follow, along with nausea, exhaustion and fatigue.

The migraine was still raging the morning of the race, prompting me to take four ibuprofen before the start. But the real challenge wasn’t just the pain; it was the overwhelming fatigue that gripped my entire body.

When the gun went off at 6:20 a.m. local time for the ‘race across the sky’, my legs wouldn’t respond. The migraine paired with a healthy dose of altitude sickness, made for a not-so-great day on the bike.

Melisa Rollins won this year’s Leadville 100 in 7:09:47. I did finish, 22nd among pro women in 8:04:19, the time a little over 17 minutes slower than last year.

Leadville Trail 100 MTB presents unique challenges for many riders, including those who live beyond the western US states, and especially those based at sea level. For instance, speaking with fellow Grand Prix competitor Danni Shrosbree, she's unable to train on any climb longer than five minutes being based in London.

Ultimately, Danni decided to use Leadville as one of her two drop races due to the financial and logistical hurdles of acclimatizing. I can’t imagine how difficult it is for riders like her.

Hayley Preen from South Africa also couldn’t race Leadville due to similar challenges. She was supposed to be my roommate at Crusher, where she was ready to race. Peta Mullens from Australia made me appreciate how lucky I am to live just two hours from Leadville. Peta will be stateside until the last race in the Grand Prix, Big Sugar.

Samara Sheppard of New Zealand struggled to push through despite having spent six weeks at altitude. She stayed in Vail, around Leadville’s altitude, and drove to Leadville to pre-ride and race.

“I’ve been at altitude now for six weeks and cannot wait to be at sea level again—to feel good again,” she shared. It’s a sentiment many of us can relate to after enduring the harsh realities of racing at high altitudes.

Science behind the struggle

My path to Leadville wasn’t typical. Even though I live just two hours away from Leadville now, I faced logistical and financial barriers to spending a proper amount of time at 10,000 feet. And this past month, life outside of cycling took the front seat.

I had to adapt to a new training style. My husband recently graduated from his medical residency in Atlanta, and maintaining the lifestyle of a pro cyclist while living in a metropolitan city at sea level for five years was no easy feat. But it taught me an important lesson: make the most of what you have.

In Atlanta, my training revolved around maximizing the limited elevation. My Strava data shows I rode up the only “proper” training climb - 4 minutes with brief downhills - 1,400 times. It wasn’t ideal, but when it’s all you have it’s a necessity.

Perhaps this is why I believed I could travel to Leadville within 36 hours of the race from Boulder and be fine. I was not fine.

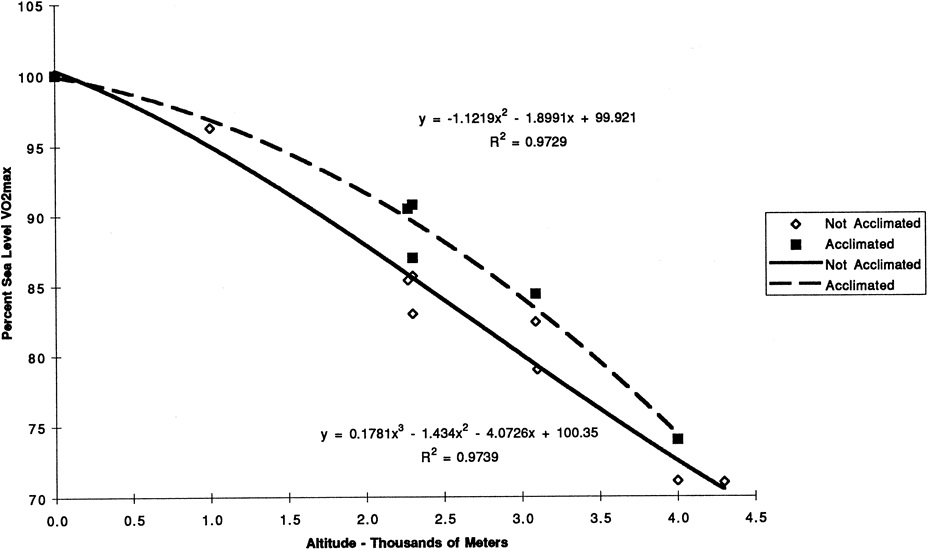

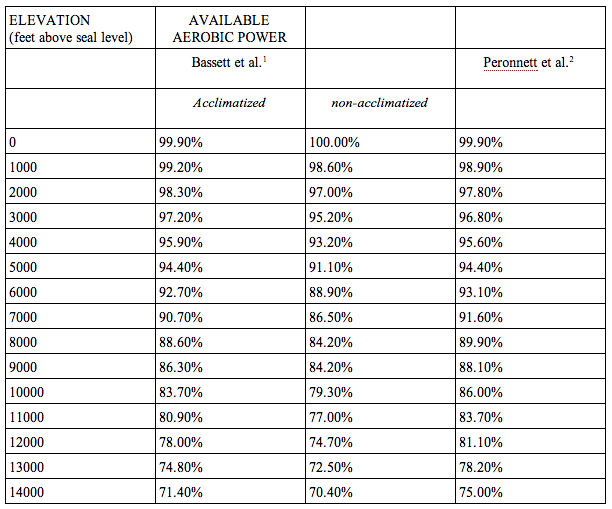

Analyzing the data using an analysis of the effect of altitude on running performance published by the National Library of Medicine (Péronnet, F. et al. 1991), a well-acclimated athlete climbing to the top of Columbine would produce 76% of their aerobic power compared to sea level, where oxygen is abundant. In contrast, an unacclimated rider would produce only 73%. At Leadville’s cruising altitude of 10k, these numbers drop further to 83.7% and 79.3%, respectively.

The impact of altitude on performance isn’t just an exponential decrease; it’s a significant reduction in oxygen availability that affects every aspect of an athlete’s performance. The higher you go, the more pronounced the effect, with a sharp decline in VO2 max as altitude increases.

This isn’t a linear drop; it accelerates at very high altitudes, making races like Leadville exceptionally challenging. Another study published by the National Library of Medicine (Bassett, D.R. et al. 1999) illustrates this using data from comparing cycling world hour records across 30 years, adjusting for differences in aerodynamic equipment and altitude.

Learning from those who got it right

Leadville 100 winner Rollins shared her experience about her preparations for competing altitude, which included taking part in the three-day Leadville Stage Race on the same course and taking the win there.

“I got to Leadville on July 24, so I was at altitude for 17 days before the race. The first few days were tough, but by day 5, I felt the same as I do at home in Salt Lake City (approximately 4200 feet above sea level). I think it helped, but everyone is different. I haven’t been able to sleep more than 6-7 hours a night since I got up here, so that may impact people differently. For me, I do OK on minimal sleep,” she said.

What is her advice? “Next year, come up for the stage race and stay! I know it’s not always possible with logistics, but the last few weeks have been so fun. I made sure all of my training was done before I arrived at altitude. It’s an interesting puzzle!”

Melissa’s approach highlights the importance of acclimatization, preparation, and understanding how your body responds to altitude.

For those of us who didn’t get it quite right this time, it’s a valuable lesson learned.