The season of Hall of Fame debates is almost over, as the results of this year’s Baseball Writers’ Association of America election are revealed Tuesday at 6 p.m. ET on MLB Network.

Both of us are BBWAA members, but we are not yet eligible to vote for the Hall of Fame. Still, that didn’t stop us from filling out our own hypothetical ballots.

First, here’s a quick refresher on how the Hall of Fame ballot works. BBWAA voting members can select up to 10 players on the ballot. Players must receive votes from 75% of the ballots cast to earn induction, and they must get at least 5% to remain eligible for the following year. They have a maximum of 10 years of eligibility on the writers’ ballot.

There’s a lot to cover with our ballots, so let’s get started. Emma is up first ...

Emma Baccellieri, MLB Staff Writer

I find this ballot pretty tricky. There are plenty of guys with cases for inclusion, as I see it, but none who look like clear auto-bids. (There are two who look like automatic inductees just by their statistics—Alex Rodriguez and Manny Ramírez—but the fact that both were not only linked to PEDs but actually suspended for them makes it … complicated.)

If you’re a Small Hall believer, I think this is a year when it could easily make sense not to vote for anyone at all. If you’re more Big Hall, I think you can make a logically coherent full ballot of 10. Personally, I’m somewhere in the middle, and I settled on six.

Two of the most straightforward for me were those who finished above 50% last year: Scott Rolen and Todd Helton. Rolen is one of the best defensive third basemen of all time and meets qualifications on offense, too. (2,000 hits, 300 home runs and 500 doubles!) Helton was always close to the line for me, but now that Larry Walker is in, Helton definitely should be, too.

With Andruw Jones, I find the defensive peak compelling enough to merit inclusion, and with Billy Wagner, he’s in such a small, elite group of closers that I think he has to be in Cooperstown.

Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated

So it was the two remaining names here that proved trickiest for me: Carlos Beltrán and Jeff Kent. In the case of Beltrán, I’d thought when he retired that he was a Hall of Famer, and I didn’t imagine there was anything that would change that. … But, of course, you know what happened next. I struggled quite a bit with how to judge Beltrán’s role in the Astros’ sign-stealing scandal. On the one hand, there is clear, unambiguous evidence of cheating that was reportedly orchestrated in large part by Beltrán, and I understand anyone who decides that disqualifies him. On the other … it’s all but impossible to suss out just how much he did, personally, and exactly how much it did (or didn’t) benefit each member of the team. Plus, there are already all sorts of ethical shades of gray included in Cooperstown. (There have been sign-stealing scandals aided by technology going back a looong time.) I think what Beltrán did was wrong. Given all the messy compromises already present in the Hall of Fame, I don’t think it was necessarily disqualifying.

That leaves Kent: no tough ethical questions here, for once, just a straightforward one of performance on the field. He’s one of the best offensive second basemen in history, if not the best, as the home run leader at the position. He was also a famously poor defender. In years past, I hadn’t thought much of his case for Cooperstown. But with this year being his final one on the ballot, I focused on it a little more, and I was ultimately convinced by an argument from Matt Martell: The offense speaks for itself to the point where the defense didn’t really matter. His managers always found his bat so valuable that it was worth keeping him where he was instead of moving him off second. A clear-cut case for the Hall? Not quite, but in his last chance on the writers’ ballot, I think Kent is just over the line for me.

Emma Baccellieri’s Ballot

- Carlos Beltrán

- Todd Helton

- Andruw Jones

- Jeff Kent

- Scott Rolen

- Billy Wagner

Matt Martell, MLB Editor

I am definitely more of a Big Hall guy, and that’s especially true when I fill out my hypothetical ballot each year. That doesn’t mean I think everybody I include definitely belongs in the Hall of Fame. Rather, it means I think they deserve more consideration for Cooperstown. Why? Because, as we see every year, our opinions of players’ careers change over time. If my support could help a player with a compelling HOF case stay on the ballot for the next election, then I believe it’s my job as a hypothetical voter (and maybe someday an actual voter) to keep the conversation about said player going.

For the first time in a while, I’ve included fewer than 10 players on my ballot: seven holdovers, one addition and one player in his first year on the ballot.

First, let’s run through the holdovers, in alphabetical order …

Bobby Abreu was a model of consistency for the better part of his career. Over his best 10-year stretch from 1998 to 2007, he slashed .302/.411/.505 and averaged 22 homers, 29 stolen bases, 157 games played and 5.2 WAR per season. His 60.2 lifetime WAR is 19th among right fielders, just behind Gary Sheffield (60.5) and ahead of two of his contemporaries, Ichiro Suzuki (60.0) and Vladimir Guerrero (59.5). He is one of six players in baseball history with at least 250 home runs and 400 stolen bases. Three are Hall of Famers—Rickey Henderson, Joe Morgan and Craig Biggio—and the other two are named Bonds.

Another way to view Abreu’s consistency is gradual peak. In Friday’s Five-Tool Newsletter, I defined gradual peak as “the period of a player’s career that begins with his first 3-WAR season and ends with his last 3-WAR season.” The purpose of this metric is to capture the length of time that a player was among the more productive players in the league. Abreu’s gradual peak lasted for 12 of his 18 seasons. In that 12-year span, Abreu posted a .301/.406/.497 slash line with an average of 21 homers, 97 RBIs, 28 stolen bases, a 133 OPS+ and 4.8 WAR per season. That’s Hall of Fame–level production for more than a decade.

The knock on Abreu is he was never considered the best when he was playing. He made just two All-Star teams and never finished in the top 10 for MVP. He would be far more appreciated if he played today because of his ability to get on base, a skill that wasn’t as widely recognized during his prime. Among players who debuted since integration, Abreu ranks 34th in times on base (3,979), ahead of Hall of Fame outfielders such as Tony Gwynn (3,955), Lou Brock (3,833), Billy Williams (3,799) and Roberto Clemente (3,656)—all of whom had more plate appearances than Abreu.

Todd Helton was the second-best first baseman in baseball for a decade, behind Albert Pujols. Helton is one of 15 players in MLB history to play in at least 2,000 games and record a career slash line of at least .300/.400/.500. All but two of them are in the Hall of Fame: Manny Ramírez, who failed multiple PED tests, and Helton.

Brad Mangin/Sports Illustrated

Helton is also one of the best defensive first basemen. He ranks eighth all-time in runs from fielding at the position. Some writers don’t vote for him because they consider his numbers inflated due to the altitude advantages at his home field in Denver. But two things greatly help Helton’s chances: Larry Walker is now in the Hall of Fame despite spending a majority of his career at Coors Field, and research in recent years shows how much of a disadvantage Rockies hitters have when playing on the road. Helton’s support is increasing; as of Monday morning, he’s received votes on 79.4% of the 180 ballots tracked publicly, according to Ryan Thibodaux’s indispensable ballot tracker. My guess is that Helton comes up just short of election this year, but he’ll eventually get in, and his induction will be long overdue.

By some metrics, Andruw Jones is the best defensive center fielder of all time. And yet, the more I’ve looked into Jones’s Hall of Fame case, the less certain I am that he belongs. Last week, The Athletic’s Jayson Stark wrote about why he didn’t vote for Jones, and his rationale was quite compelling. Stark cites research conducted by sabermetrician Chris Dial, who concluded that Jones wasn’t an elite defender for as long as the metrics suggest.

Stark writes:

Dial told me his research shows that after Jones’ first four years, his weight began to balloon, while — in a related development — his speed and jumps declined. Dial also found Jones’ defensive value in those years was inflated by his arm and the many “discretionary outs” he all but stole from his infielders and corner outfielders on softly hit balls that center fielders don’t normally haul in.

Jones also hit 434 career home runs, but he was more of a one-dimensional slugger at the plate than a great hitter. During Jones’s nine-year peak, from 1998 to 2006, he was the fifth-best center fielder by offensive WAR (35.7)—behind Jim Edmonds (41.5), Bernie Williams (38.8), Johnny Damon (38.4) and Carlos Beltrán (38.4)—and third-best by OPS+ (119), behind Edmonds (143), Ken Griffey Jr. (132) and Williams (127). Of that group, only Griffey is in the Hall of Fame, while Edmonds, Williams and Damon fell off the ballot after their first or second years of eligibility.

In the end, my doubts weren’t enough for me to remove Jones from my ballot, even though I believe Edmonds and Williams are more worthy of Cooperstown.

Jeff Kent has more home runs than any second baseman in MLB history. That should be enough to get him in the Hall of Fame, but if you need more convincing, I’ll refer you back to Emma’s explanation for why she came around on Kent. You can also read Will Laws’s deeper look at Kent’s career and his case for Cooperstown.

Scott Rolen is one of the most well-rounded third basemen in baseball history. Only Mike Schmidt (10) has more seasons with a Gold Glove and a 120 OPS+ among third basemen than Rolen (8). He’s also one of only five third basemen to hit 300 or more home runs and steal at least 100 bases. The other four are Schmidt, George Brett, Chipper Jones and Adrián Beltré.

Earlier this month, Tom Verducci wrote about Rolen’s Hall of Fame case, which included this incredible nugget about his baserunning: Rolen scored 32% of the time he reached base and took the extra base 49% of the time.

Verducci writes:

The average major league player last year scored 30% of the time he reached base and took the extra base 41% of the time. Rolen was a superb baserunner, especially considering his position. Only three Hall of Fame third basemen took the extra base at a higher clip than Rolen: Pie Traynor (60%), Brett (54%) and Freddie Lindstrom (54%). Even with his injuries, he ranks fourth at the position in doubles (517).

Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated

At his best, Jimmy Rollins was a five-tool player and the second-best shortstop of his era, behind Derek Jeter. I’ve written about Rollins’s Hall of Fame case a few times now, and my argument comes down to this: He’s the most HOF-worthy shortstop to debut since Jeter in 1995. If Rollins doesn’t get in, that would mean MLB would go, at the earliest, nearly two decades without producing a Hall of Fame shortstop. The next three guys with a legitimate case: Xander Bogaerts (debut 2013), Francisco Lindor (’15) and Carlos Correa (’15).

Billy Wagner is the best pitcher in league history at missing bats. Among pitchers with at least 800 innings pitched, he ranks first with a 33.2% strikeout rate and .187 batting average against. The lack of volume holds him back in the eyes of some voters, but that’s not Wagner’s fault. His job was to get outs over one or two innings, oftentimes in high-leverage situations, and he was as good at that as any pitcher in baseball history not named Mariano Rivera.

Now, let’s get to the one newcomer and one addition …

Carlos Beltrán could do everything. He hit for average and power from both sides of the plate. He could run, field and throw. He raked in the postseason—before he played for the 2017 Astros.

Put it all together, and Beltrán is a top-10 center fielder of all time. He ranks eighth in WAR (70.1), fifth in home runs (435) and RBIs (1,587) and third in doubles (565) among primary center fielders. He’s also one of the best switch hitters of all time, ranking eighth in offensive WAR (66.6), sixth in runs (1,582), fourth in home runs and total bases (4,751), third in RBIs and second in doubles. Everybody who ranks ahead of him is either in the Hall of Fame or named Pete Rose.

At his peak, few players ever combined the power and speed of Beltrán. He had seven seasons with at least 20 home runs and 20 stolen bases. That’s more 20/20 seasons than any center fielder in history. In fact, only three players at any position recorded more 20/20 seasons than Beltrán: Barry Bonds (10), Bobby Bonds (10) and Abreu (9).

Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated

Like Emma, I struggled a bit with Beltrán’s role as one of the architects of the Astros’ illegal sign-stealing scheme, but in the end, I couldn’t help but consider all the previous instances of electronic sign stealing in baseball history. Also, the late Gaylord Perry is—deservedly so—in the Hall of Fame despite throwing illegal spitballs throughout his career. For me, at least, Beltrán’s sign stealing is more similar to throwing the spitter than it is to using steroids.

Mark Buehrle is the only addition to my ballot. I’m not sure he belongs in the Hall, but I am sure he was one of the more durable and consistent pitchers over the first 15 years of the 21st century, and to me, that’s worthy of another year of Hall of Fame consideration.

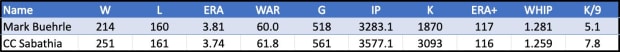

Over his 16-year career, from 2000 to ’15, Buehrle ranks second among starting pitchers with 60.0 WAR, behind Roy Halladay (62.4). If you widen that gap to include the first 20 seasons of the ’00s, he ranks sixth, behind Justin Verlander (72.1), Zack Greinke (66.6), Clayton Kershaw (65.5), Halladay and CC Sabathia (61.8)—one Hall of Famer (Halladay), three active players who are future Hall of Famers (Verlander, Greinke, Kershaw) and one likely future Hall of Famer (Sabathia).

Sabathia is a really good comp for Buehrle. Look at this:

via Baseball Reference’s Stathead

Sabathia has a better HOF case than Buehrle. CC pitched longer, struck out more batters and won a Cy Young. But, it’s worth noting Buehrle retired while he was still an effective pitcher, whereas Sabathia had several rough seasons during the back half of his career.

Let’s return to gradual peak, because nearly Buehrle’s entire career was essentially his gradual peak. I’ve also included his steep peak, which I defined as “the period of a player’s career that begins with his first 5-WAR season and ends with his last 5-WAR season.”

Career: 16 years, 60.0 WAR, 214–160, 3.81 ERA, 1.281 WHIP, 1,870 K, 3,283⅓ IP, 117 ERA+

Steep peak: 9 years, 4.5 WAR, 15–11, 3.79 ERA, 1.263 WHIP, 128 K, 33 GS, 223 IP, 122 ERA+

Gradual peak: 14 years, 4.2 WAR, 14–11, 3.81 ERA, 1.281 WHIP, 124 K, 33 GS, 217 IP, 117 ERA+

That’s remarkable consistency. Every year except his first season—when he was used as a reliever—and his final season, Buehrle was worth at least 2 WAR. Even in his last year, when he posted 1.2 WAR, he still went 15–8 with a 3.81 ERA and four complete games. Simply, Buehrle was never bad, and more often than not, he was very good.

- Bobby Abreu

- Carlos Beltrán

- Mark Buehrle

- Todd Helton

- Andruw Jones

- Jeff Kent

- Scott Rolen

- Jimmy Rollins

- Billy Wagner