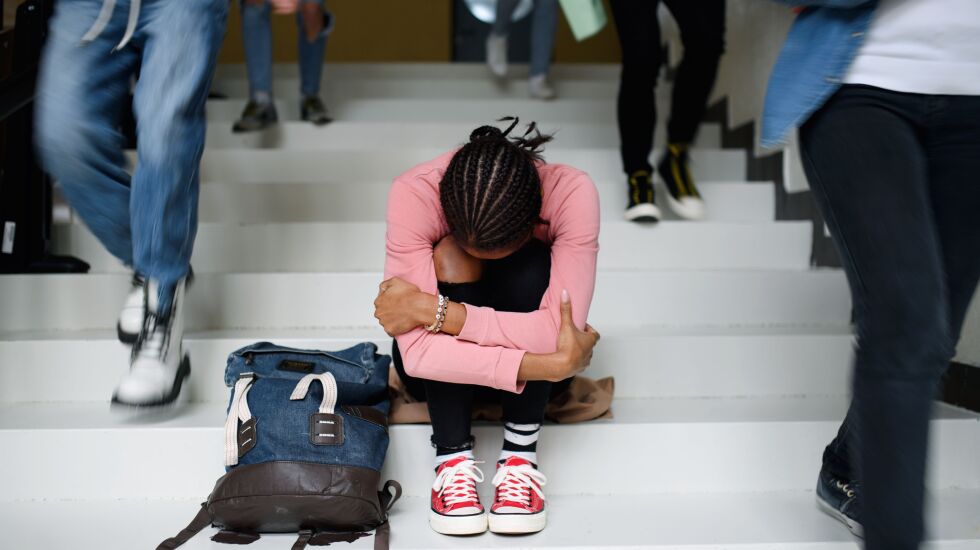

Aniya is a young teen living in the West Englewood neighborhood of Chicago. She is like many other 17-year-old girls: dedicated to school, her family and dance team practices.

Although she comes across as a happy, successful teen, there’s more to Aniya than meets the eye. For 50 minutes every week, she sits in a circle with other young women in her school to share her more difficult thoughts: persistent feelings of loss, grief and despair. Neighborhood violence can make it feel like she’s living in a “war zone,” and there is overwhelming pressure to “make it” to college and escape.

Aniya’s story is far from unique. In 2017, our two organizations — the University of Chicago Education Lab and Youth Guidance — teamed up with the city and Chicago Public Schools to systematically serve 750 girls with the Working on Womanhood program, in which Aniya takes part, and study its effects on post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression. We believe this partnership between the city, schools, non-profit organizations and researchers can serve as a roadmap to address young women’s mental health in communities across the country.

First, we set out to understand the scale of the problem. When researchers from the Education Lab surveyed a sample of 9th to 11th grade girls across 10 neighborhood high schools in Chicago, they found a staggering 38% exhibited signs of PTSD — more than double the rate experienced by service members returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, and that was before the pandemic. These trends reflect a more significant mental health crisis among our nation’s young women. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that nearly 1 in 3 high school girls nationwide reported that they seriously considered suicide in 2021. That’s a jump of almost 60% from 10 years ago.

Public officials are starting to take notice. After the pandemic, the U.S. Surgeon General took the rare and extraordinary step of issuing a public health warning on the youth mental health crisis, and we’ve seen ongoing pressure from local leaders for greater focus on behavioral health diagnosis and treatment.

But it can be difficult to know what to do to intervene effectively, much less what works. So, as a second step, we identified all eligible girls who could have participated in the 10 neighborhood high schools, over 3,500, and randomly assigned 750 to the Working on Womanhood program in addition to already available support.

Reducing PTSD symptoms

When we looked at the outcomes of the two groups in spring 2018, we found it reduced the rate of PTSD symptoms among participants by 22%, a meaningful and significant reduction. While more research is needed, this is one of a few rigorously studied programs proven to systematically mitigate the harms of mental health challenges facing young girls today at moderate scale. This is particularly important since public school mental health services suffer from underinvestment, which makes it all the more critical to target limited resources to proven programs.

Unfortunately, evidence-based mental health programs tailored to young women are few and far between, in part because such programming has traditionally focused on support for young men. This inequity needs to change. Researchers, funders and policymakers should recognize that investing in the mental health of young women means stronger communities over the long term. Our research into Working on Womanhood may be among the first school-based clinical studies of its kind, but it certainly cannot be the last.

Finally, we need solutions for women of color designed and delivered by women of color. Treatments are more effective when they are informed and delivered by people who have insights into their needs, especially when it comes to mental health. As young women navigate traumatic events in their day-to-day lives, providers must know what they’re up against. We’ve seen that with this program, but this lesson holds for other mental health interventions as well, whether in school or clinical settings.

Ultimately, the program was transformative for Aniya, and, evidently, many other girls. Equally important is the need to take effective practices and scale them in partnership with the public sector and keep studying program outcomes to understand what works best for which girls under which contexts.

This collaborative effort is a Chicago success story that can serve as a roadmap for helping schools address young women’s mental health. If we want to take on this challenge, we need to acknowledge its disparate impacts, invest in evidence-based interventions, and ensure treatments are informed and delivered by those most impacted. With these tools at our disposal, schools in Chicago and around the country can lead this endeavor.

Monica Bhatt, Ph.D., is senior research director at the University of Chicago Education Lab. Nacole Milbrook, Psy.D., is chief program officer at the national nonprofit Youth Guidance.

The Sun-Times welcomes letters to the editor and op-eds. See our guidelines.

The views and opinions expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Chicago Sun-Times or any of its affiliates.