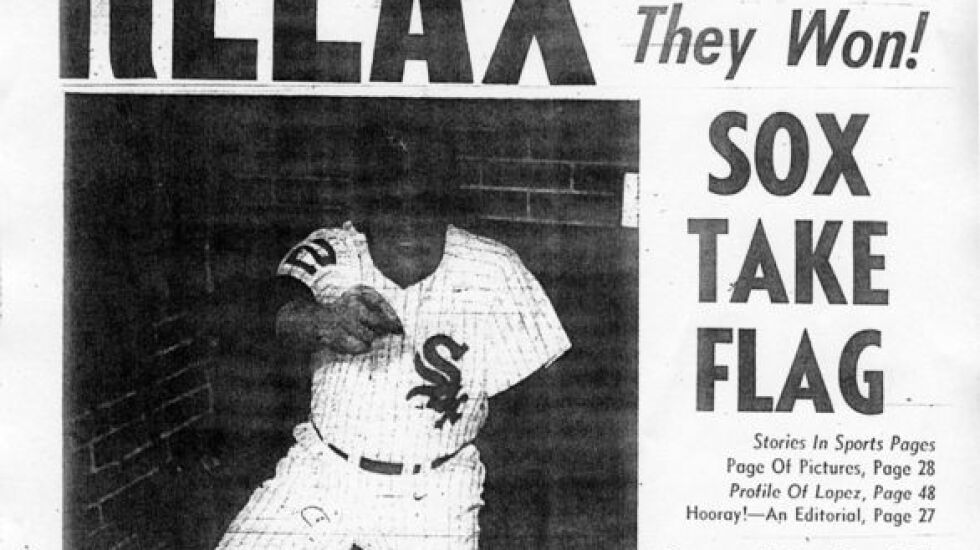

When the White Sox won the pennant in 1959, air raid sirens wailed across the city.

It was the height of the Cold War. Thousands of Chicagoans, fearing an imminent attack, panicked.

They wanted a calming, trusted voice — so many called the operator.

That voice is almost silent now. AT&T has announced that it’s ending operator and 411 directory assistance services for all but its traditional wired landlines. The company points out that most customers can look up what they want online.

“The demise of 411 is not just the demise of an operator but also the final closing of the human element in telephone communication,” said Josh Lauer, an associate professor of communication at the University of New Hampshire who is writing a book about the cultural history of the telephone.

About two years after Alexander Graham Bell made the first telephone call in 1876, the first switching station in Chicago opened at 118 N. La Salle St, according to Robert H. Glauber, writing in the summer 1978 edition of the magazine Chicago History.

The station allowed any telephone to be connected to any other through a central office.

“The central offices were crowded, noisy and inefficient,” Glauber wrote. “The operators making the connections and disconnects yelled back and forth at one another and shouted at the customers to make themselves heard.”

By 1882, there were 2,610 telephones in use in the city and, by 1920, nearly 600,000, according to Glauber.

In the early 1900s, demand for phones was so great that the Bell System — the phone company — set up centers to train operators, with Chicago’s opening in 1913.

A short promotional film from 1926 shows smiling trainees — all young women — learning how to operate switchboards and speak correctly.

“Through training in the art of inflection, she gains in these gentler qualities of unfailing courtesy so essential everywhere,” according to one of the film captions.

The trainees also are seen dancing and playing the piano in one of the “rest rooms.”

By the time of “The War of the Worlds” radio broadcast in 1938, which unintentionally convinced many Americans that men from Mars were invading Earth, some big-city switchboards were as long as half a city block.

People called operators in tears. Switchboards lit up like Christmas trees.

“One lady . . . said they are as far as Chicago now,” said Lorene Fechner, a Montana operator interviewed for an AT&T short documentary made in 1988. “I thought, if they’re traveling that fast, they’re going to be in Missoula before I get off duty.”

In Chicago, according to news reports, panicked customers left restaurants in the middle of their meals, some without paying.

There was another false alarm about 20 years later.

“That memorable early fall night in 1959 when the White Sox clinched the pennant, every civil defense siren in the city screamed out in celebration,” Glauber wrote. “Within moments, central offices all over the city were overwhelmed by callers trying to find out from each other and the operators if Chicago were under attack.”

Some operators, not knowing what else to do, told callers the siren meant “take cover,” according to a Chicago Sun-Times story from that time.

“The Illinois Bell Telephone Co. said it handled the heaviest deluge of calls since the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt,” the Sun-Times reported.

Over the years, telephone companies tried, with limited success, to remind customers that calling an “information” operator didn’t mean asking for any and all information. These operators were specifically assigned to look up phone numbers that callers couldn’t find in a paper directory.

But, as Emily Goodmann wrote in 2019 in “Information & Culture: A Journal of History,” operators often used their best judgment in deciding whether to answer a caller’s question.

“Yesterday someone wanted to know how to spell ‘conscientious objector.’ Another woman asked if she should use 10 eggs in her angel food cake instead of 12 because her eggs were unusually large. This morning someone asked if I knew Mrs. Nixon’s real name,” Goodmann wrote, quoting an anonymous writer to Chicago Sun-Times columnist Ann Landers.

As Goodmann, a media historian at Northeastern University in Boston, puts it, operators were like a “proto-Google.”

“She was certainly considered to be an encyclopedia, a dictionary, a Guinness Book of World Records, a cookbook,” Goodmann said.

Inevitably, though, with advances in technology, the need for switching operators diminished — particularly during the late 1940s through the mid-1960s, when Bell and AT&T made a big push to encourage customers to direct dial one another.

“She hadn’t vanished, but the goal was to make her obsolete,” Goodmann said.

Sharon Griggins started working in 1970 as an operator for Illinois Bell in Waukegan when she was 16. She worked mostly to help people with collect and long-distance calls.

But callers still enjoyed hearing the human voice on the other end of the line, particularly young men from the nearby naval station at Great Lakes.

“There were sailors who would call, and I guess they knew I had a younger-sounding voice, and they’d say, ‘What time do you get off?’” said Griggins, now 68 and living in Seattle.

Illinois Bell discouraged “frivolous conversations,” she said.

At the end of an eight-hour shift, Griggins said, “You’d go home, and you didn’t feel like talking to anybody.”

Eventually, technology improved to where operators weren’t needed even for long-distance calling.

“So directory assistance was the last vestige of a human operator,” said Lauer, the communications professor.

Today, for most people, the internet has replaced the need even for that.

In 2021, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were 3,870 telephone operators working in the United States. By 2031, the bureau forecasts a 25% drop in that number. Operators are listed as one of the “fastest-declining occupations” along with typists, word processors, and watch and clock repairers.

Griggins was visiting Chicago a few years ago and stopped at the Museum of Science and Industry, where she saw an old switchboard on display — much like the one she’d used.

She said she thought: “Oh, my God, my job is in a museum now!”

In some ways, that’s sad, she said.

“It is a crime that we can no longer talk to people about our problems,” Griggins said. “It is nearly impossible to reach a living person when you’re trying to get some help with a problem these days. That’s terrible. What they really want you to do is just go away.”