Nearly a month after a catastrophic storm with hail the size of baseballs pummeled Central Texas, half of the roofs in an office complex in Round Rock are still topped with shattered red tile. On the rest, the broken tiles are covered by “shrink-weld” tarps and white plastic sheeting that temporarily protects the offices, indicating that insurance has likely kicked in and missing tiles may soon be replaced.

“It looks like somebody sprayed the roof with a machine gun,” said Cody Risner, the owner of Risner Roofing.

Risner has a list of 250 customers needing storm-related roof repairs; about half are still waiting for roofing materials, which remain in short supply because of damage caused by Hurricane Ian in Florida in 2022.

A 10-minute drive away, on Rustlers Road in the Hermitage neighborhood, hail damage is even more apparent. Rocks and bricks precariously hold down tarps and blankets are thrown over blasted-out windshields on dozens of cars covered with dents up to 6 inches in diameter. Many of these cars may never be fixed if their owners were un- or underinsured.

Enrique Delgado, the owner of Blue Trucking towing company, and his employee, Rene Escalone, are loading up hail-damaged cars to take them to a junkyard in Waco, which generally gives owners about $400. This is the fourth time they’ve visited here since the storm walloped the area on September 24.

Magali Rivera, like other people in the neighborhood, couldn’t afford to fix the dents in her car but managed to replace its broken windows for a little over $400. She rents her house which she said has roof damage, but hasn’t heard if or when the landlord will fix it.

Last year, Texas reported 14 storms that caused over $1 billion in damage, the most ever recorded in Texas.

She’s been through this before: Two years ago, another hailstorm hit the neighborhood.

Hail is causing an increasing amount of damage in a larger swath of Texas. Every year since 2008, there has been over $10 billion in property damage from hail nationwide, said Ian Giammanco, the lead research meteorologist for the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS), a nonprofit funded by the property insurance industry. “And Texas is a big piece of that pie because Texas is a big state with a lot of population and major urban centers that are right smack in that zone that sees hail every single year.”

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) started tracking severe storm events, including hailstorms, in 1980. Last year, Texas reported 14 storms that caused over $1 billion in damage, the most recorded in Texas in a single year in the history of that system.

Last year, Texas also led the nation in the number of “severe” hail events, according to the Insurance Information Institute. NOAA defines severe hail events as those with hail 1 inch and larger in diameter. The agency recorded 641 severe hail events in Texas in 2022 and 1,120 through October of this year. Insurance risk assessor Verisk estimated that in 2021, 17 percent of Texas properties were subject to hail damage.

Part of the reason for the increase in hail damage is that the population along the Interstate 35 corridor between Central and North Texas, where hail is prevalent, has boomed. Areas that were once sparsely populated ranchland are now densely settled. And the average size of all U.S. houses has grown an average of 1,000 square feet since the 1980s. “We build bigger houses on smaller lots and put it all close together,” Giammanco said. “When a hailstorm happens, that [damaged material] has to get replaced.”

Other research shows that the size of hailstones is increasing because of climate change and so is the area most often affected. These days, Texans living in the north and central parts of the state will likely experience hail larger than 2 inches in diameter at least once a year.

Hail is created when updrafts in a thunderstorm carry droplets of water to higher altitudes where the air is cold and the droplets freeze into ice. As the pieces of ice move through the air, they grow in layers as moisture from the air accumulates and larger hailstones form. When those stones become too heavy, they fall.

But proportionally, with climate change, there are now fewer small hailstones because warmer temperatures are causing them to melt before they hit the ground. That warmer air holds more moisture and causes larger updrafts in a thunderstorm, which, in turn, creates larger hailstones.

“Hail requires thunderstorms and thunderstorms are driven by the hot and moist air near the ground,” said Eric Bruning, a professor of atmospheric science at Texas Tech University. “And so, spring and summer are the seasons that typically favor hailstorms.”

Historically, the month with the most hail damage in Texas is April, according to NOAA. There is evidence, however, that the hail season in the United States is likely lengthening because of climate change.

But hail can happen any time of year in Texas, according to John Nielson-Gammon, Texas’ state climatologist, with a peak in the spring and a secondary peak in the fall.

Not all hail is the same. “You can have everything from something that’s like a snow cone slushy substance, all the way to hail that can withstand almost 4,000 pounds per square inch of pressure,” Giammaco said. “That’s an extremely strong piece of ice.” Four-inch hail can hit the ground at 90 to 100 miles per hour, which can cause severe damage.

Surprisingly, fewer than 20 people worldwide are killed by hail every year, although injuries from hail have seen an uptick, Giammanco said. Sixty people were hospitalized at an outdoor event in Fort Worth in 1995 and, two years ago, 100 people who couldn’t reach shelter were injured in a 2021 hailstorm at Red Rock Amphitheater in Colorado.

Yet hail and the thunderstorms—called supercells—in which most hail is created remain understudied, experts say, because modeling them is challenging. “To predict a thunderstorm is something like predicting where in the bottom of a pan of water, the water will boil–where just one of those bubbles will come up,” Bruning said. “That’s sort of like what it’s like to forecast thunderstorms.” To forecast hail within these storms is even more complex.

However, with the huge uptick in hail damage, financial support for research has increased.

Managed by Colorado State University, the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail, and Snow Network receives funding from NOAA and the National Science Foundation. It trains volunteers to put out hail pads–12-inch squares of 1-inch-thick Styrofoam covered in aluminum foil–and document the dents created in them to determine what size of hailstones fell. Volunteers get together for hail pad-making parties.

Scientists also monitor social media around the country for posts about large hail. When they see one, they may fly to the area to measure stones and scan them with handheld infrared laser scanners. That data can later be used to create an exact 3D model of the hailstone.

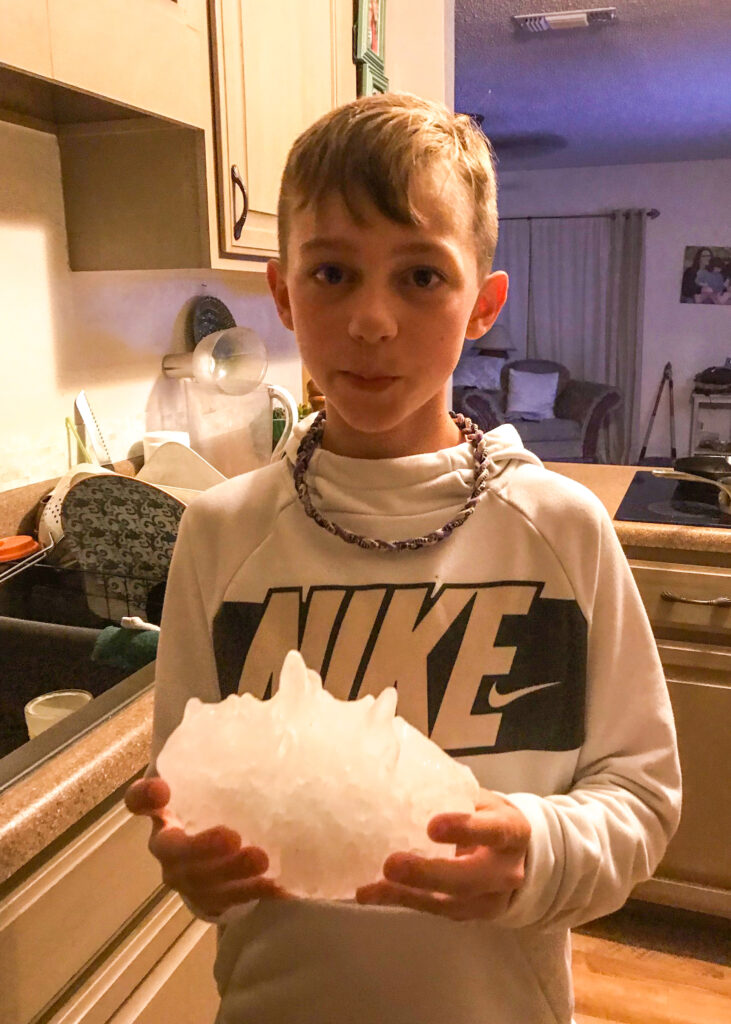

A 6.4-inch, 1.3-pound hailstone that fell in Hondo in April 2021 holds the current Texas record. Carol Twilligear first posted a picture of that record-setting rock on Facebook. A local television station noticed her post and notified the National Weather Service. Twilligear estimates that the stone was at least seven inches in diameter and had more spikes on it when she first picked it up in her front yard. “It was wicked-looking,” she said.

Twilligear, of course, had to pass it around to neighbors, so the stone shrunk before scientists showed up to confirm the record a few days later. “When they came, I had four people in my kitchen, measuring that thing and talking to me. Both my grandkids were here, so they got to be in on the whole thing,” she said. “It was pretty exciting.”

The Hondo hailstone may seem like a huge chunk of ice, but even bigger ones have fallen elsewhere. The largest recorded hailstone by weight fell in Bangladesh in 1986. It weighed 2.2 pounds. And the largest by diameter—8 inches—fell on Vivian, South Dakota in 2010.

Matthew Kumjian and two scientists from Canada and Australia who all collect and measure hailstones reported by various people have theorized that the largest a hailstone can be is 8.7 inches in diameter–the size of a bowling ball—and 3.1 pounds in weight. He brought a 3D printing of this theoretical hailstone to the Second North American Workshop on Hail & Hailstorms in Boulder, Colorado last year. The model was a hit with the hail nerds in attendance, where “everyone was taking selfies with it.”

Most hail damage involves commercial and residential buildings—about 90 percent of the total loss reports. Homeowners can protect themselves by asking for hail-resistant roofing materials. IBHS has created a roof shingle rating system, which rates shingles by their resistance to hail damage. A highly-rated product, marked by a green dot, can qualify homeowners for an insurance discount, though they cost 5 percent more than traditional shingles.

The Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex has the highest percentage of hail-resistant roofing installed in the United States, Giammanco said. But it’s only on 10 percent of roofs. “We’re starting the race behind. But we are starting to understand there are materials that can handle this hazard,” he said. “We just have to get them put onto buildings.”

There aren’t any hail-resistant cars. Only about 20 to 30 percent of the property damage by hail is to automobiles, with an average claim running about $4,000.

Some car dealerships in hail-prone cities like Lubbock have begun to protect their inventory with hail nets. Gene Messer Hyundai installed them 10 years ago. Since then, despite storms raining down two-inch hail, it has had only one “minor” incident of hail damage because they couldn’t drive cars under the nets fast enough, according to Brendan Cimino, the dealership’s general manager.

After a hail incident, building and auto repair contractors flock to an area to seek business from victims like Magali Rivera in Round Rock. Some are reputable; others may not be. To avoid price gouging and scams, Giammanco suggests asking around about local contractors and looking for a contractor who is licensed, insured, and bonded, and checking with the Better Business Bureau or chamber of commerce for ratings and recommendations.