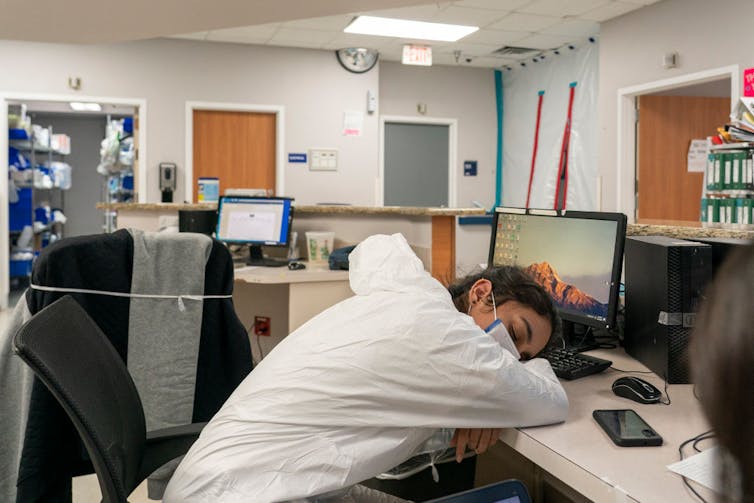

Health care workers often put the health and safety of their patients first, neglecting to take care of themselves. By providing continuous services around the clock, many experience short and poor-quality sleep, risking not only their own health and safety but also increasing the risk of making errors that can affect patient safety.

I am an occupational health researcher who studies work, sleep and health among health care workers. My research has found that emotional labor – such as using fake smiles to hide true feelings – and work-family conflict – such as clashing demands between roles at work and at home – are both linked to depressive symptoms among health care workers. And poor sleep quality can amplify the effects of these stressors, resulting in worse mental health.

Health care workers face multiple challenges

Shift work and long hours are common components of a health care job. Night or rotating shifts that require being awake during the night and sleeping during the day can misalign the biological clock, which is typically oriented to wake during the day and sleep during the night. This mismatch can result in sleepiness and impaired performance at work, along with poor and shortened sleep during the day.

Moreover, health care workers can face many other work stressors, such as exposure to infectious diseases and chemical hazards, bullying and violence, high physical workloads and time pressure. These require learning to manage emotions and feelings during interactions with patients and co-workers.

Even so, some professionals in various fields may need to repress their own emotions in order to do their work effectively. In our study of over 1,000 U.S. public sector health care workers who directly and indirectly work with patients, my research team and I found that over half had to mask their feelings at work without addressing them, and increasing levels of emotional labor were linked to increasing symptoms of depression.

In addition, health care workers often experience conflicting demands between their work and family roles. For example, a parent may need to take time off from work to take care of a sick child. Research on U.S. workers has found that work-family conflict can have adverse physical and mental health effects.

In our study, about half of the health care workers we surveyed reported that their work interfered with their family life, while about 30% experienced family life interfering with work. Importantly, these conflicts were linked to poor mental health such as depression.

Poor sleep and mental health

The U.S. National Health Interview Survey, an annual household interview of adults conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, found that 36% of workers had an average sleep duration of less than seven hours a day in 2018. A minimum of seven hours of sleep is recommended for optimum health and well-being. Sleep deprivation is increased among health care workers, affecting 45% of those surveyed. Our research found an even higher rate: Over half of the health care workers we studied reported fewer than seven hours of sleep per day, and one-third complained of sleep disturbances.

Moreover, we found that one-quarter of these health care workers experienced depressive symptoms, a rate three times higher than the depression prevalence of the general U.S. population.

Sleep plays a critical role in mental health. Short or poor sleep is a strong risk factor for depression and poor mental well-being. And it is well known that stress can interfere with sleep quality. Our study found that disturbed sleep intensified the effect of work stressors such as emotional labor and work-family conflict on the depressive symptoms of health care workers. That is to say, these work stressors may both directly affect health care workers’ mental health and indirectly affect mental health by harming their sleep.

How can health care workers improve their sleep?

The most common nondrug-based recommendations to improve the sleep of shift workers include scheduling, bright light exposure, napping, sleep hygiene education and cognitive behavioral therapy.

There is no concrete evidence yet available on the best sleep schedule for health care workers on night or rotating shifts. However, while most night workers begin their daytime sleep shortly after returning home in the morning, laboratory studies on older adults found better night shift alertness and performance and longer sleep duration with an afternoon-evening sleep schedule.

Based on those findings, my research team is currently testing the effectiveness of an afternoon-evening sleep schedule in real-world settings for health care workers who are regularly working nights. We are also exploring whether such a sleep schedule is acceptable to health care workers and easy enough to integrate into their daily lives.

Workplace is critical to improving sleep

Building a healthy work environment is a critical and meaningful way to improve sleep. A large number of work stressors – such as shift work, work demands, lack of social support, workplace hazards and negative behaviors of co-workers – all contribute to the poor sleep of health care workers.

Evidence-based workplace programs that prevent workplace violence, provide emotional support after difficult incidents and offer flexible scheduling could all help reduce the underlying problems behind poor sleep. Workplaces may consider an integrated approach that both reduces work-related stressors and promotes the sleep and health of their workers. For example, a healthy workplace may allow their employees to select their own work schedules and provide training on sleep hygiene.

Moreover, many sleep promotion programs need the workplace to get involved. Sleep education requires employer support, and light exposure and nap rooms require environmental changes in the workspace. Allowing workers to participate in the decision-making process may encourage them to get involved and take action to improve their own health, which could transform sleep and overall health for workers, especially those in the medical field.

Yuan Zhang receives funding from the National Institute of Health (NIH) Grant Number R01 AG044416 and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Grant Number 2 U19 OH008857.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.