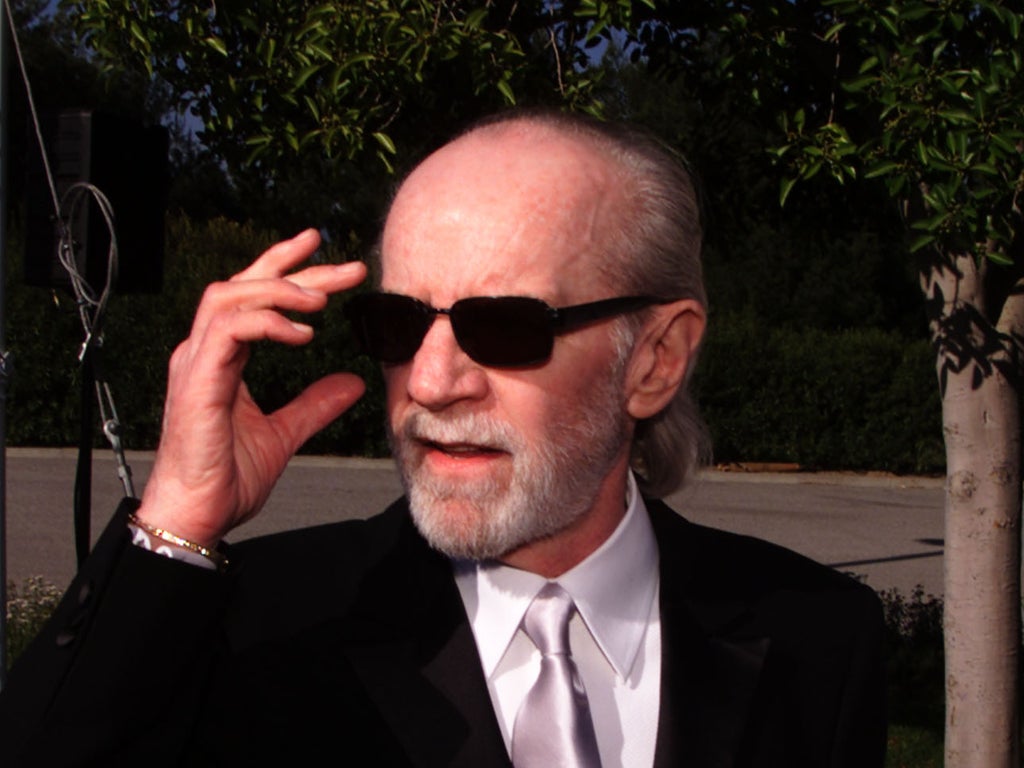

When news broke of a leaked proposal to overturn Roe v Wade – the landmark ruling that enshrines abortion rights in the US – it didn’t take long for George Carlin’s name to start trending. The late stand-up quickly went viral earlier this month thanks to a widely shared routine from his 1996 HBO special Back In Town, in which he takes aim at the anti-abortion movement. “They’re not pro-life,” he preaches, his long grey hair pulled back into a ponytail. “They’re anti-woman.”

Over a quarter of a century after it was first delivered, and 14 years after Carlin’s death from heart failure at 71, many on social media felt Carlin’s routine perfectly captured the prevailing anger. “What’s really interesting is that no one else’s routine went viral,” says Judd Apatow, who has directed the eagerly awaited two-part documentary George Carlin’s American Dream. “Even though there have been hundreds of comedians since George Carlin, no one had a bit that you would even put up to say: ‘Here’s another great bit that discusses this.’ He was the best.”

Carlin has a vintage routine for many of contemporary America’s ills. After another round of mass shootings last weekend in Buffalo, New York and Laguna Woods, California, some shared the skit from the 1988 special What Am I Doing in New Jersey? where Carlin incredulously screams: “You see now they’re thinking about banning toy guns, and they’re going to keep the f***ing real ones!” His continued relevance is especially remarkable given that stand-up is often considered an ephemeral art form. “Comedy is not like fine wine,” says Apatow. “Comedy is more like a banana: it just instantly rots. So the fact that, 14 years after he passed, his material seems better than ever really says a lot about how deep and brilliant it is.”

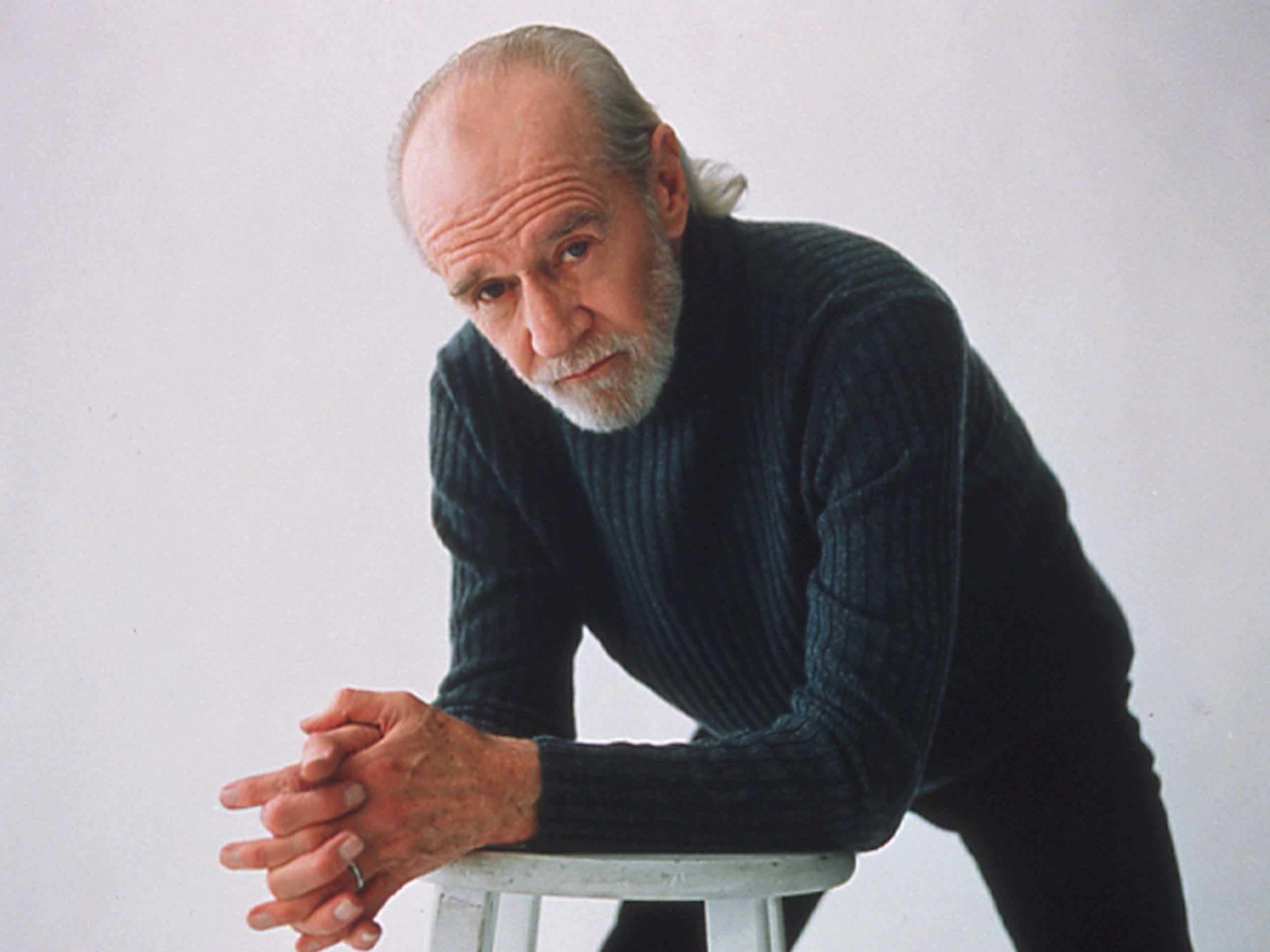

So what is it that has given Carlin’s work such longevity? Apatow says it takes a “soup of influences and experiences” to make a great comedian, and to concoct a Carlin you first have to start with a childhood dream of becoming an all-round entertainer, like Carlin did with his idol, White Christmas star Danny Kaye.

Born in Manhattan in 1937, Carlin began his career as a radio DJ before honing his skills as a physical performer on television variety shows in the Sixties. His talent for impressions and creating sound-effects with his voice would be put to much darker use in later material, like the moment in 1992’s Jammin’ in New York when he conjured the sound of the planet shaking off humanity like a dog ridding itself of fleas. “He was the Danny Kaye of the microphone,” says Apatow. “That style of comedy is very precise and musical.”

Another crucial ingredient was Carlin’s phenomenal dedication as a writer, which long-time manager Jerry Hamza witnessed first-hand. “It was ridiculous,” says Hamza. “He’d start at seven o’clock in the morning, banging away on a computer on the way to a private plane. On the five-hour flight he’d be pounding away on the computer, then he’d get into the limo and go to the hotel and do more work on the stuff. Then he’d go to the show, do the first half, and during intermission he’d do some more. After the show he’d do even more.”

This single-minded dedication didn’t always make Carlin the easiest company. Hamza first started working with Carlin in 1980, and recalls that his first impression was of a “rude and abrupt” character. “Of course, he was doing a lot of cocaine in those days, which doesn’t exactly make you humble,” explains Hamza. “He had a roadie that would put out lines of cocaine on the dressing-room table, and then he was off to the races.”

As it turns out, consuming, in Carlin’s words, “as much cocaine as there was in the immediate three-county area”, isn’t a terribly healthy lifestyle choice. Hamza was with Carlin in May 1982 when he suffered his second life-threatening heart attack while watching a baseball game in Los Angeles. “It was horrible,” says Hamza, “Don’t ever have a heart attack in a stadium.” The near-death experience was something of a wake-up call. “It scared the hell out of him, and George was a fearful guy to begin with,” says Hamza. “He didn’t come across that way. He came across very composed, but he was an isolationist. You’ll never hear: ‘George Carlin was at this Hollywood party…’ because he wouldn’t go. He’d rather go climb up a tree, stay in his own head and work on his material. But the heart attack frightened him.”

By that point in his career, Carlin was at a crossroads. Having emerged as a strait-laced, suit-and-tie-wearing stand-up, he had already undergone one radical transformation to become a long-haired voice of the counterculture in the Seventies. By the end of that decade, however, he had fallen behind the zeitgeist. At the time, Cheech Marin of rising counterculture stars Cheech & Chong described Carlin and his wordplay-heavy style of comedy as “obsolete”.

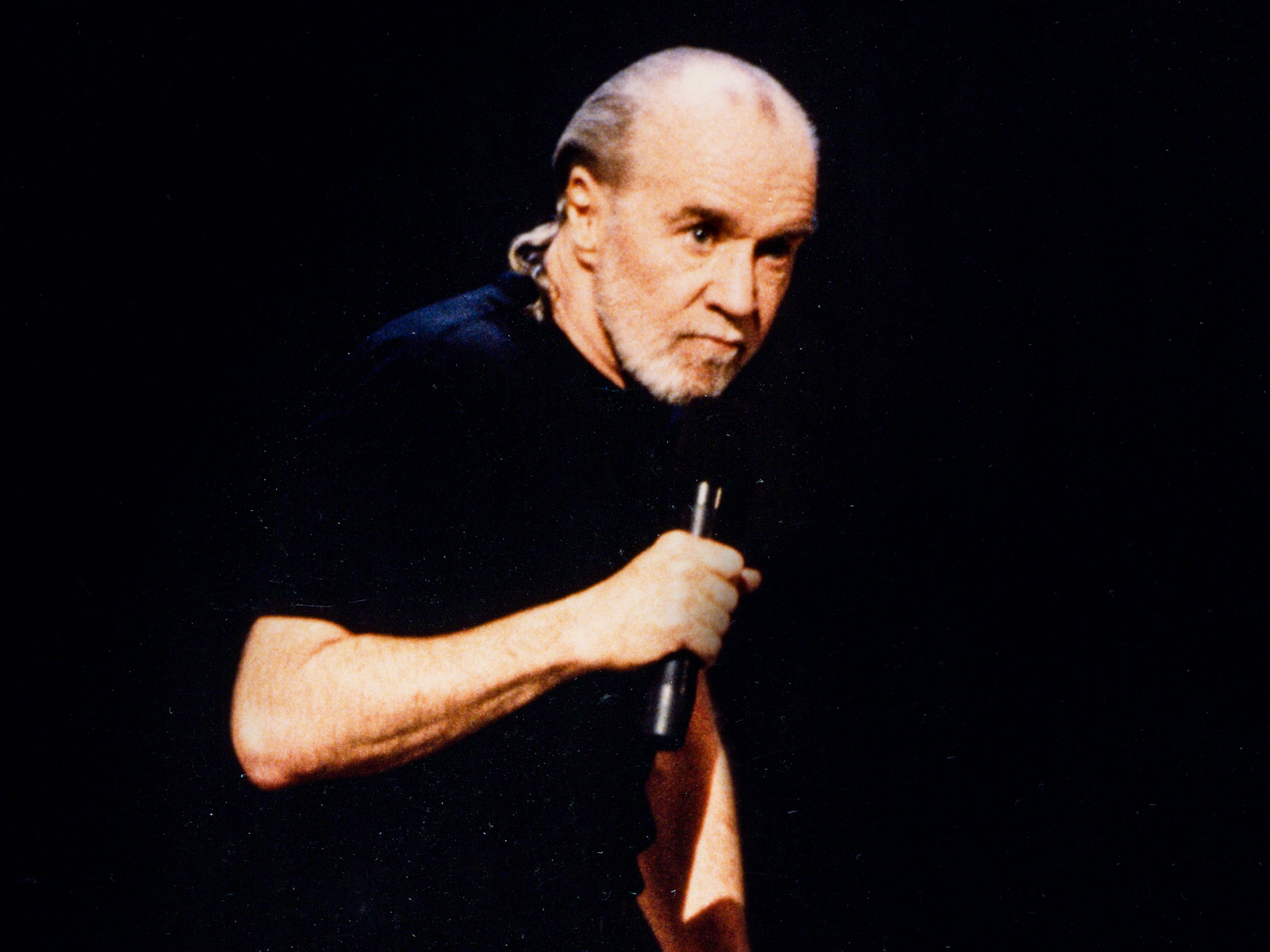

Five months after his heart attack, Carlin booked himself a date at New York’s Carnegie Hall for a show that would be filmed for an HBO special, Carlin at Carnegie. He was determined to announce his comeback with a bang. “George came up with a formula,” explains Hamza, “And one part of it was to hit them in the balls with a heavy-duty opening line.” With the religious right in the ascendency after the election of Ronald Reagan, Carlin came out and delivered his killer opener: “Have you noticed that most of the women who are against abortion are women that you wouldn’t want to f*** in the first place?”

If you’ve seen the Carlin clip currently doing the rounds, you’ll notice an important difference between that line and the one he delivered in Back In Town 14 years later. By then, it had become: “Why is it that most of the people who are against abortion are people you wouldn’t want to f*** in the first place?” Carlin’s daughter, Kelly, tells me this is an example of how his routines changed over time. “Someone was putting a clip package together the other day, and they had the ‘women’ one, and I was like: ‘No, you’ve got to do the more recent one,’ because he obviously did have a good think about it,” she says. “He was a man who evolved his thinking, and obviously evolved his language with that.”

Carlin was obsessive about words. One of Kelly’s early memories of watching her father perform was at 1972’s Milwaukee Summerfest, when Carlin was arrested for “disturbing the peace” after his now legendary “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television” routine. “It was absolutely terrifying,” she remembers. “It was a time in America where people like my father felt very much targeted by the government. The whole world was in a lot of chaos, and there was all this stuff going on like [the National Guard shooting students at] Kent State and the Vietnam protests. It all felt very divided and dangerous.”

Carlin was eventually released after a judge found he had not, in fact, “disturbed the peace” by reciting the words, “s***, piss, f***, c***, c***sucker, motherf***er and tits”. Nevertheless, when the same routine was broadcast on the radio, it led to a court case and, eventually, a Supreme Court decision that would largely define the extent to which the federal government could regulate the speech broadcast on television and radio.

My dad was a progressive, he was always for the underdog

Ever distrustful of government interference, Carlin received a huge ovation during Jammin’ in New York for declaring, “I have certain rules I live by. My first rule: I don’t believe anything the government tells me.” This stance has led him to be venerated by right wing sites like Breitbart and caused some on social media to claim that he may well have been onboard with the anti-vax movement were he alive today. It’s an idea Kelly is quick to shoot down. “The reality is he’s a man of science,” she says of her father. “He had a major heart condition. He would have gotten a vaccine. He would have hated Trump. Lots of people go: ‘Oh, he would have loved him because he speaks out and he’s politically incorrect.’ No! He’s a white male businessman! C’mon people, have you been watching him for 50 years? From day one he was making fun of these motherf***ers.”

She adds that even for Carlin, there were limits to free speech, and certain things he’d never say. “Of course he didn’t like politically correct language, but at the same time he taught me from day one that the n-word is the worst word and you can never say it,” she says. “He taught me you should never punch down, and that Black and brown people are getting f***ed all day long by this government, and women, too. My dad was a progressive; he was always for the underdog.”

Raised a Catholic and educated at Manhattan’s Corpus Christi school, Carlin spent much of his life railing against organised religion. “I tried to believe that there is a God, who created each of us in His own image and likeness, loves us very much, and keeps a close eye on things,” he said in his famous “Religion is Bulls***” routine from 1999 special You Are All Diseased. “I really tried to believe that, but I gotta tell you, the longer you live, the more you look around, the more you realise, something is f***ed up.” That same year he played Cardinal Glick in Kevin Smith’s subversive religious satire Dogma, although Hamza says that despite the popularity of that role, and his performances as time-travelling mentor Rufus in the first two Bill & Ted movies, he never enjoyed acting as much as stand-up. “On a movie set they put you in a little trailer and you just sit there,” says Hamza. “He hated that. He wanted to be by himself on a high wire.”

By the end of his career, Carlin had adopted a dark comic persona that ostensibly revelled in human misery, especially if Americans were involved. “He used to say: ‘I read in the paper that 600,000 people died in Peru or someplace’ and he’d be quite disappointed because he wanted it to be right here,” says Hamza, who recalls having to change the name of Carlin’s 2001 comedy special Complaints and Grievances at the last minute. “The title was gonna be ‘I Kinda Like It When a Lotta People Die’, but 9/11 happened a few weeks before the show.”

Although the jokes remained as hilariously bleak as ever, Hamza remembers that when the cameras stopped rolling, Carlin showed a different side of himself to the fans who’d come to New York’s Beacon Theatre for that taping. “It’s funny, George never displayed his patriotic feelings, but he was still a kid from New York City,” says Hamza. “When the HBO show was over we would try to tag on an extra 30 minutes so the audience felt like they’d had a night. I remember him singing [1894 vaudeville song] “The Sidewalks of New York” wrapped in the American flag at that show after 9/11.”

Carlin continues to matter, and his material remains so relevant, because he saw so clearly the way society was heading. For Apatow, the bleakness and cynicism of Carlin’s later work was a deliberate provocation from a comedian who was at heart a disappointed idealist. “I always thought he was trying to go so dark that it would push you to the light,” he says. “A lot of his material seems to be a warning about what might happen to our environment, about what was happening with corporate interests taking over our government and the media. Now, all these years later, you realise he wasn’t overreacting. Back then people thought: ‘He’s so dark, this is too far.’ Now we watch it and think it may not be dark enough.”

‘George Carlin’s American Dream’ is on HBO Max 20 and 21 May