Frank Zappa released a staggering 23 albums and played nearly 800 concerts during the 1970s - but as ever, the stats hide a multitude of life experiences. In 2015 Mark Ellen looked back on a decade that gave Zappa some of his highest highs and lowest lows.

Imagine for a minute it’s Los Angeles in the autumn of 1969 and you’ve been invited to a house in the Hollywood Hills. It’s a sprawling, tree-filled complex full of lawns and outbuildings. You cross a timber walkway and head to a dark studio bunker, its walls pinned with self‑taken snaps of adventurous sex and a band called The Mothers Of Invention (who’ve just split up). And there in a haze of cigarette smoke is a stick-thin, shirtless figure with his hair in a ponytail, making final adjustments to an album he’s almost finished called Hot Rats.

A lot of the neighbours are rock stars too and throw parties all the time – Jim Morrison, Buffalo Springfield, Love, Canned Heat – but nobody’s smoking weed and falling in pools around this place. The owner threw the occasional bash at his old house, the famous Log Cabin in Laurel Canyon, but as he didn’t drink or take drugs and was easily bored. His wife Gail tells me he’d just start bossing people about: “Okay, you guys go over there and write a song about The Roxy.”

So instead of flooring bottles of tequila, he’s in this basement at four in the morning working out that if he plays his latest track Peaches En Regalia at half-speed he can overdub some percussion and a solo played on a bass guitar which, when speeded back up, will give the whole thing a twinkly cartoon finish.

Frank Zappa, it’s immediately obvious, was not like other men. He really wasn’t. He was manically driven, extravagantly gifted, utterly unique. And possibly mad. He grew up in the Mojave desert where his father was a chemical warfare specialist (the infant Frank used to play games in gas masks, thinking they were space helmets).

In 1958, at the age of 17, he’d found an unlistenable album by the avant garde composer Edgard Varèse and read it as a barcode of his own personality. He used it as an “intelligence test”: if people enjoyed the record – like his classmate Don Van Vliet, the future Captain Beefheart – they could enter his social circle. If they didn’t, they were barred.

Aged 23, Frank had decided the only way to sell his off-the-wall blues, soul and doo-wop recordings was via the same medium that launched Elvis Presley: television. So he talked his way onto the prime-time The Steve Allen Show as a leading exponent of “cyclophone music” – sounds produced, oh yes, by plucking and scraping bicycle spokes.

When Columbia Records sent their curt response to one of his early demos – “no commercial potential” – Zappa adopted the phrase as a mission statement. In ’66 he’d formed The Mothers Of Invention, a group so doggedly in thrall to his compositional genius that at least one of them, drummer Jimmy Carl Black, performed the entire double-album Freak Out! without understanding a single note he was playing. Their first single was reviewed on Britain’s Juke Box Jury and reckoned to be “the worst record ever made”.

“He had a nervous energy that almost had a hum to it,” Gail Zappa remembers down the line from Los Angeles. “And his appearance was very strange when I met him – raggedy T-shirts and wool tuxedo trousers held up by suspenders [braces]. He was so thin you could get two of him in there! And big, huge shoes, very pointy. His strangeness was magnified by his gait, the rhythmic way he moved with articulated joints, like a puppet as if suspended in the air. And he worked all night. I burnt the candle at the other end. I didn’t live with the vampires!”

So this was the man adding the final touches to Hot Rats – eccentric, insatiable, highly accelerated. But one other key factor went into the making of this record: Frank needed a hit. He’d entered the 70s virtually penniless and had to change tack. The Mothers’ music was so impossibly complex the public simply couldn’t digest it. And it was a nightmare to perform.

“He was a workaholic,” their sax and reed player Bunk Gardner observes. “We could play three hundred songs at the drop of a hat and had to memorise it all as he wouldn’t let us use music. He’d make signs with his fingers to change from five-eight time to seven-eight or whatever and then jump up in the air and come back down and we’d be into another song.

“There was a riot after the Sportzplatz show [in Berlin] – they threw eggs, hard green pears, litres of paint, metal, even a section of the railing ripped from the front. Zappa handed out medals to the band for surviving this particular incident.”

But Zappa was paying for it and had no real sympathy at all. The final nine-piece Mothers were surviving on $250 a week between them. When Jimmy Carl Black rang his studio to complain about the wages – “the band is starving!” – Frank merely taped the conversation and released it on the album Uncle Meat. So he needed a hit. And needed it very badly indeed.

Frank booked Sunset Sound in Hollywood – studio home of Joni Mitchell, The Doors and The Beach Boys – to try a bold new experiment: an instrumental rock album played mostly by jazz musicians, among them Max Bennett, Jean-Luc Ponty, Don ‘Sugarcane’ Harris and the only member of the Mothers he’d retained, his supremely talented multi-instrumental sidekick Ian Underwood.

The sole vocal performance (on Willie The Pimp) was by his old schoolfriend, though relations were now strained as Beefheart was blaming the commercial failure of his epic Trout Mask Replica on its producer (Zappa), while The Captain’s ludicrous studio methods – like refusing to wear headphones – had driven Frank round the bend.

Hot Rats was jazz you could handle and mass-market rock that made you look arty and sophisticated

Hot Rats was released as the new decade unfolded, and it was a masterpiece. Everything about it chimed with the times. Its magically inventive guitar solos seemed spontaneous – fitting with the new vogue for improvisation pioneered by Cream, Hendrix and the Grateful Dead – but they were actually fiercely controlled and edited, and woven between brutally tight jazz riffs on which Underwood was often overdubbed 10 times on different instruments (Frank chose Sunset Sound for its ground-breaking 16-track console).

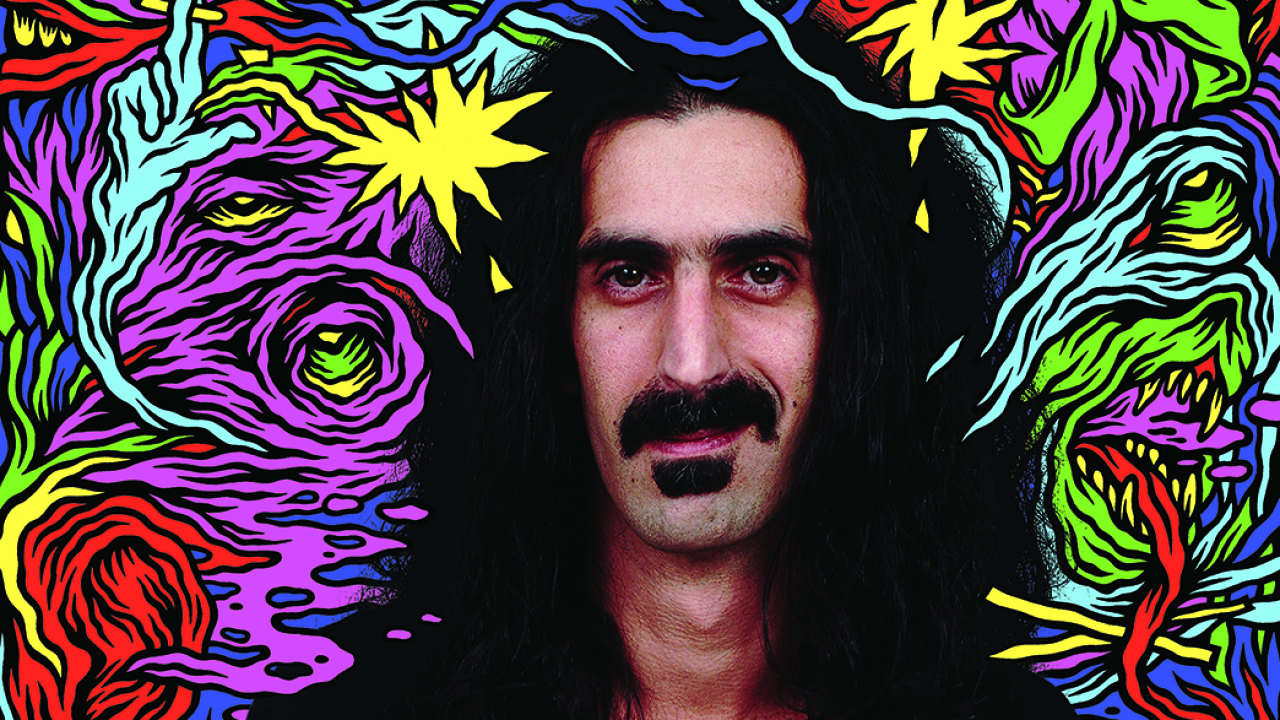

Even the cover fitted with the new psychedelia, an infra-red snap of an androgynous freak clambering from a mold-filled swimming pool, her hair suggesting she’d been plugged into the mains (she was in fact ‘Miss Christine’ Frka of all-girl band The GTOs, whom Frank was producing).

The effect was extraordinary. Everybody played it. Hot Rats was jazz you could handle and mass-market rock that made you look arty and sophisticated, a left-field notch above other big albums of the year by Led Zeppelin, the Allman Brothers, Santana, the Stooges and Mott The Hoople. “You haven’t heard Hot Rats? Don’t worry, mate [hollow laugh]. Get back to yer Sabbath and yer MC5!”

Hot Rats was warmly received in the States, and even made the Top Ten in Europe. And it altered Frank’s image: he was no longer the sinister creep plying his wiry trade by lobbing cynical hate-bombs at the conventional world; he was a vastly talented composer working at the bleeding edge of both rock and technology.

To capitalise on his newfound fame, Zappa launched himself on a 97-date world tour with a new band including Underwood, jazz keyboardist George Duke and fun-sized vocalists Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan of The Turtles (who used the stage names Flo and Eddie). On the rare occasions he got back to Hollywood, he reworked unused Mothers material from ’69 and released it as a pair of albums that delighted hardcore Zappaphiles but reminded everyone else he was a self-confessed “grouchy son of a bitch”.

The first was Burnt Weeny Sandwich (named after his favourite lunch), complex out-takes in finger-plaiting time signatures. But not many people heard the second record – live recordings and studio trickery – as they couldn’t get past a sleeve so repulsive that some shops refused to stock it. Spotting a copy of Man’s Life magazine on which a naked bloke wrestled unsuccessfully with skin-chewing mammals to the coverline ‘WEASELS RIPPED MY FLESH’, Frank told the artist, Neon Parks, he wanted that as the album title, adding, “What can you do that’s worse than this?”

Warming to the challenge, Parks fashioned a pastiche of a grooming advert in which a smiling Brylcreemed hunk mutilates his jawline by shaving with an electric weasel. Some of the music was hard going too, not least Prelude To The Afternoon Of A Sexually Aroused Gas Mask.

And 10 weeks later, a brand-new Zappa record appeared, Chunga’s Revenge, a collection of jazz-blues jams and tales of on-tour debauchery recorded with his travelling band (though three albums a year was standard, in ’79 he released five).

But a major new project was now looming on the horizon. In endless post-show motel rooms, Zappa was thrashing out a movie script, a surrealist fantasy about the escapades of a rock group (played by the new Mothers) in the fictional town of Centerville, a ludicrous self-indulgence he co-directed that would sink without trace.

Never see this film. All you need to know is that Ringo Starr played ‘Larry The Dwarf’ (dressed as Zappa), Keith Moon was ‘the Hot Nun’ and the critics gave it the shoeing it so richly deserved for its “whimsically impenetrable plotline” and “absurdist sub-Monty Python humour.”

200 Motels tanked completely. And the music didn’t fare much better. Panicked by lyrics about sex with groupies, the promoter at London’s Albert Hall cancelled three performances of its soundtrack, declaring it “filth for filth’s sake.” Zappa was incensed. “The woman who runs the place is insane,” he hit back. “Very prude and very sick. She gave us a list of twelve words we couldn’t say on stage and one of them was brassiere!”

The mainstream market that embraced Hot Rats was now baffled by his art-rock movie but worse – far worse – was around the bend, the incident that soured his relationship with Britain forever. The 1971 European tour had already come unstuck: an audience member had let off a flare gun in Montreux Casino, setting fire to the heating system and destroying the venue and all Frank’s equipment (an event immortalised by Deep Purple in Smoke On The Water as they watched the chaos from a hotel on Lake Geneva).

But six days later at The Rainbow in Finsbury Park, as Zappa counted the band into a sarcastic rendition of The Beatles’ I Want To Hold Your Hand, a guy in the front row clambered onstage and, incensed by his girlfriend’s infatuation with him, pushed Frank into the orchestra pit.

“My head was over on my shoulder and my neck was bent like it was broken,” Zappa remembered (it was a concrete floor). “I had a gash in my chin, a hole in the back of my head, a broken rib and a fractured shin. One arm was paralysed. The band thought I was dead.”

My head was over on my shoulder and my neck was bent like it was broken. I had a gash in my chin, a hole in the back of my head, a broken rib and a fractured shin. One arm was paralysed. The band thought I was dead

Frank Zappa

“And he’d broken his nose,” Gail adds, “and smashed the side of his face. There was a line round his neck where it had been twisted. Bust jaw. Broke his leg and a couple of bones in his shoulder.”

His assailant was jailed for a year for “bodily harm.” Zappa was sentenced to six months in a wheelchair, his crushed larynx making his voice deeper and one of his legs now shorter than the other (as revealed in his ’79 track Dancin’ Fool). Unable to tour, he added the sax and flute player Napoleon Brock Murphy and trombonist Bruce Fowler to the line-up and piled into LA’s Paramount Studios to make two mostly jazz albums, Waka/Jawaka and The Grand Wazoo.

He recorded at the house with Beefheart too, Gail remembers, “often just reading stuff the other had written. And spent time with Keith Moon as he loved Moon’s eccentric thinking and humour. A lot of long-distance phone calls. He didn’t mind his drinking, no. It’s not our job how other people get to heaven.”

By now the rock press were confused – if not terrified – by Zappa, who seemed snide, lofty and cantankerous. He’d double-bluff them by saying things like, “I’m shy but I don’t like to talk about it.” I was 18 at the time and couldn’t work him out at all. On the outside he seemed like another long-haired hippie, but inside he was as far from peace and love as was possible to imagine.

He detested all drugs as “people think it gives them a licence to be an asshole”. He thought mainstream rock was shallow, self-serving and preposterous – “And I hate love songs,” he sneered at the time. “They gag me. It’s difficult to accept they’re the ultimate art form. And these soul groups who talk about how much ‘soul’ they have… like they’re out there sweating – and looking at their watches.”

His lyrics ignored the big picture in favour of tiny fetishistic details – obsessions with ponchos, dental floss and zircon-encrusted tweezers – and he was incapable of saying anything fond about anyone or anything. Affection didn’t exist in his life, only weird sex. Dinah-Moe Humm on Over-Nite Sensation was about a girl who reckoned no one could give her an orgasm, a challenge Zappa keenly accepts.

Camarillo Brillo was an erotic adventure with a flame-haired mystic hippie. He hired the Ikettes as backing vocalists (including Tina Turner), who were astonished to discover they were singing lines like: ‘I’ll ignore your cheap aroma/And your Little Bo Beep diploma/I’ll just put you in a coma with some dirty love.’ (Ike Turner famously declared, “What is this shit?” and left the studio.)

Frank sounded obscene even when he was just trying to be flip. Asked about his music, he said, “You can’t write a chord ugly enough to say what you want to say sometimes so you have to rely on a giraffe filled with whipped cream.”

All the boys in my house at college thought it was hilarious. To us, the man was a cryptic genius working at the coalface of the avant garde and clearly seeing more sex than a policeman’s torch: excellent! But the girls thought different. To them, Zappa was a grotesque and irksome pervert whose soulless music knotted the knees and brought dance floors to a shuddering halt.

“I like recreation,” Frank shrugged at the time when asked if his songs were autobiographical. “I’m a human being. You go on the road, you strap on a bunch of girls. My wife grumbles every now and then but hey, she’s my wife!”

He didn’t write those songs to piss me off. He played them to me and asked me what I thought of them and I tried to be encouraging… they always made me laugh anyway!

Gail Zappa

How was it for Gail when these tales of monstrous shagging appeared on his albums? “Well, if you’re in a rock and roll band and you’re ‘journalling’ your experience, what are you going to write about?” she points out. “Stuff that happens on the road. It’s an occupational hazard that goes with the territory. But he didn’t write those songs to piss me off. He played them to me and asked me what I thought of them and I tried to be encouraging.

“And a marriage won’t work if you try and get away with shit. The stuff they might be based on – a relationship with someone else – that might have bothered me, but the songs themselves had a different function: they were just a document, it wasn’t the man himself. And the problem is they always made me laugh anyway!”

Over-Nite Sensation sold well and Frank launched into the follow-up, again focusing on dazzling musicianship and tightly constructed comic vignettes. Apostrophe(’) did even better – his biggest album, it entered the US Top 10 – and buried among its tales of eskimos trudging across the tundra, strange pancake breakfasts and the gleeful exposure of fraudulent fortune-tellers was perhaps the best and most subtle satirical piece he ever wrote, a three-minute masterpiece called Uncle Remus.

I’d never really understood Frank’s attitude to the outside world until I discovered that, while recording in a cabin in Cucamonga in ’65 when he was 24, he’d accepted an offer to produce a joke audio tape for a stag party. The comical squeals of a female friend faking sexual ecstasy made local police suspect he was making blue movies in there; the place was raided and Frank charged with “conspiracy to commit pornography.” He returned from his brief jail sentence a hardened man – cynical, embittered – and never trusted any kind of authority again.

From then on he thought all consensus views were farcical, especially the hippie movement which he considered even more sheep-like and pathetic than the tedious world of the ‘straights.’ He dedicated his ‘66 track Call Any Vegetable on stage to the blissed-out “citizens of San Francisco” (‘Call any vegetable,’ the lyric ran, ‘and the chances are the vegetable will respond to you’), and in ‘67, let’s not forget, he released We’re Only In It For The Money, whose sleeve lampooned Sgt. Pepper, the sacred cow of the new hippie economy.

But for Uncle Remus, Frank’s forensic eye for detail nailed the lamest and most laughable aspect of the revolution: posh white college kids whose idea of counterculture was growing an afro and scampering up to Beverly Hills ‘to knock the little jockeys off the rich people’s lawns’ (jockeys are West Coast garden gnomes). Which is like ringing a doorbell and running away. It’s immaculate in its withering sarcasm and has a great chord sequence by George Duke.

But a spanner was about to get chucked in Frank’s overburdened works – he sued his manager Herb Cohen for skimming too much profit from DiscReet Records, the label the pair had co-founded. Cohen counter-sued and froze Frank’s use of early Mothers recordings. Zappa bypassed DiscReet by signing to Warners who then refused to release his quadruple Läther album, which he then sold to Phonogram. At that point, Warners sued him.

He could only make money by touring and thus hit the road again, hiring original bassist Roy Estrada and Roxy Music’s Eddie Jobson on violin, soon to drift off to Jethro Tull and Yes.

The worst moment was when the Mothers tried to sue him. After all he’d done for them… Frank said, ‘I’m going to take the masters into the desert and we’re gonna burn them ’cos if I can’t have my own work then no one else will either!’

Gail Zappa

“He sued Warners, he sued EMI… so many record labels,” Gail remembers. “But the worst moment – this was in the 80s – was when the Mothers tried to sue him over the late-60s recordings. After all he’d done for them. He’d hand-taught them how to play everything and had never wished them ill. And he’d just been diagnosed with a terminal cancer. And those motherfuckers tried to sue him! And Frank said, ‘I’m going to take all the masters into the desert and we’re gonna burn them ’cos if I can’t have my own work then no one else will either!’

“Makes it hard to believe in heaven,” she adds, “as the idea that Jimmy Carl Black is now hanging out with Frank is appalling.”

Wandering into a biker bar in Nashville called Fanny’s in 1977, Zappa was struck by the talent of a 27-year-old guitarist called Adrian Belew and invited him to audition for the touring band.

“He gave me a dozen songs to learn,” Belew recalls, “stuff like Andy and Wind Up Workin’ In A Gas Station – really, really hard – and I’d wake up, play along to the records until I passed out and do it again the next day. For a week. I got the job, though he’d auditioned fifty others apparently.

“He wanted you to play his music correctly and consistently. It wasn’t about you injecting your own creativity into it, it was, ‘Here’s the music, play it right every damn night’ – though he gave us all our spotlight in the set, so he didn’t want to crush your soul or anything! It was so complex you had to play it correctly or it would just fall apart.

“And we had a ball. I was like a puppy at his elbow! I couldn’t get enough of the guy. He was full of information and funny as heck and had this great way of talking. One rehearsal, I was moving my foot pedals around and he said, ‘If you’re done playing house, would you like to join us?’

“His mind was constantly in motion, constantly creating – more, more, more. He’d pull out sheets and start writing music in airports and on the plane. The Baby Snakes film was edited from three nights – two three-hour shows a night with no gaps between songs, incredible. He recorded everything – even soundchecks, which could be three hours long. He created a whole Zappa universe, a different world. Nothing else existed. I’d eat, drink, sleep Frank Zappa every day and I thoroughly enjoyed it.”

Belew had left to join David Bowie when the NME sent me sent to review Zappa at Hammersmith Odeon in ’79. Frank was about to release his sharp and political rock opera Joe’s Garage, though he never played a note of it. Onstage he was controlling to a fascinating degree, conducting the band while perched on a stool in a pair of dreadful buckled sandals (with socks), and ordering the audience to either “stand up” or “be sedentary”, and we dutifully obliged.

A sublime Frank moment occurred at the end, which told you as much about him as his hardcore fans. Someone at the front chucked a book onstage. “Zappa starts leafing through it, looking delighted,” my review records. “It’s passed around the whole band who all crack up in hysterics. We’re treated to an extract – ‘A Clinical Aid To The Canine Birth Process,’ advising the use of sterilised scissors.”

Frank headed back to Hollywood to complete a home studio he was building called The Utility Muffin Research Kitchen – which, I hardly need to tell you, is the name of the laboratory in Muffin Man on Bongo Fury – and began working on new material for You Are What You Is. And when he wasn’t making music, he and Gail were recording their children arguing and playing it back at deafening volume to try to make them behave.

And when he wasn’t making music, he and Gail were recording their children arguing and playing it back at deafening volume to try to make them behave

It’s hard to imagine Frank as a parent but Gail paints a typically offbeam picture. He allowed the kids to swear, she tells me, but they couldn’t be malicious. “There was no such thing as bad words, Frank believed, only bad intent.”

And so his greatest decade drew to a close, a staggering 23 albums released and around 780 live performances, among them many of his most inspired moments of satire and invention. But there was one more release on the schedule: the arrival of his fourth child, Diva. This was greeted with a blizzard of enquiries from the press, mainly because he’d called his first three Moon Unit, Dweezil and Ahmed.

“If it’s a boy,” Frank told reporters, “we’re going to call him Burt Reynolds. Not Burt Reynolds Zappa,” he added, “just Burt Reynolds.”

And if it’s a girl?

“Clint Eastwood.”