The phrase ‘hard to pin down’ was, very possibly, invented for Brian Eno. Never has a person involved in the production of music (and by our definition, so many worlds beyond that) had so many pigeonholes built for him and then abandoned.

He’s a synth whizz, having been the flamboyant VCS3 man for ’70s art rockers Roxy Music’s first couple of albums, then taking his electronic knowledge to Berlin to help sculpt ‘the big three’ albums for Bowie in the city, most famously on the single Heroes and track Warszawa from the b-side of Low. And more recently (although not that recently) he became something of a champion – probably one of the only champions, actually – of the Yamaha DX7, and one of the few people to wrestle with its FM synthesis and win.

Eno is also famous for bringing that word ‘ambient’ to music production throughout the 1970s and 1980s with albums like Music For Airports and On Land. And his list of contributors moves well beyond Bowie, with album releases with everyone from Talking Heads’ David Byrne (My Life in the Bush of Ghosts) to Passengers, where Eno teamed up with U2.

Yet perhaps his finest collaborations come by way of the excellent albums The Pearl, with Daniel Lanois, and Ambient 2: The Plateaux of Mirror with Harold Budd; both extraordinary records if ever you want to explain peak ambient/chillout music to anyone.

Renaissance man

Speaking of U2, this would be the band with whom Eno would reach top form wearing yet another hat, that of producer. He was in the studio chair alongside Lanois for many of the superstar band’s strongest albums including The Joshua Tree, The Unforgettable Fire and Achtung Baby. Add that to productions with Ultravox! (the first incarnation), James, Talking Heads, and many more and Eno could be said to have been ‘quite busy’ over the last five decades.

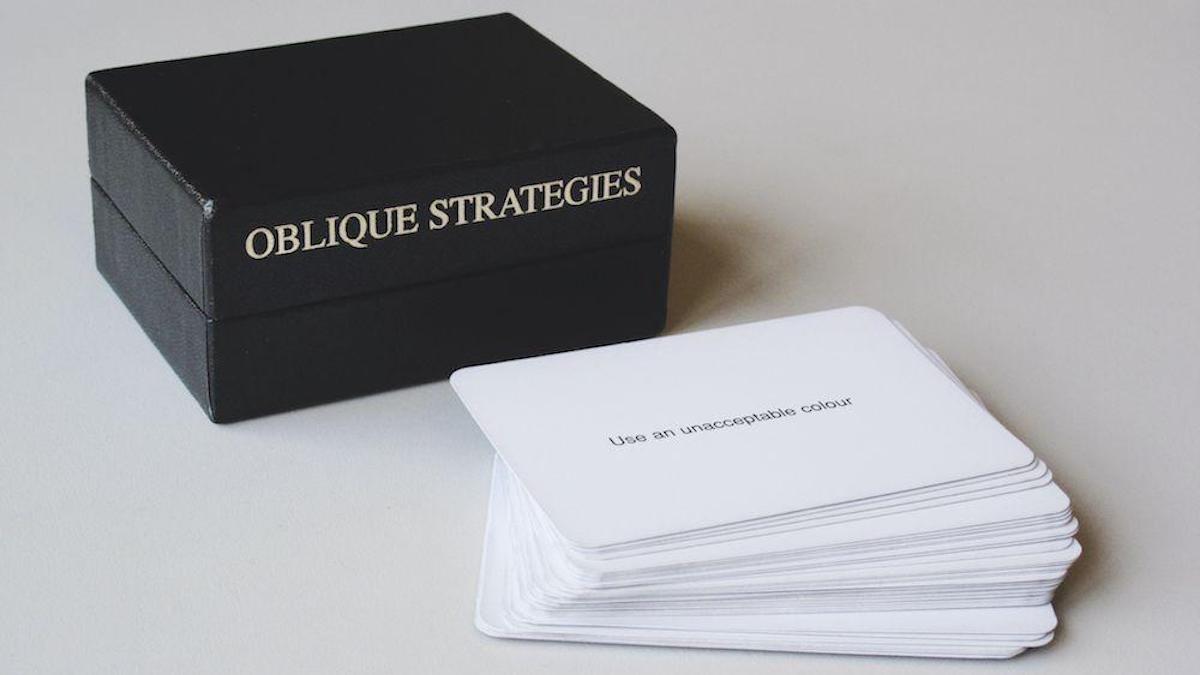

But we’re not finished yet, because not only has Eno been the creative spark behind so many projects and collaborations, he’s inspiring everyone in the art of composition, with everything from iOS apps – including the generative app Bloom, and Scape that ‘makes music that thinks for itself’, both developed with Peter Chilvers – to his infamous Oblique Strategy cards.

These were developed by Eno close to five decades ago and, while the name might sound quite artsy, are quite simply quotes on playing cards that help you out when you get stuck in a creative rut in the studio (or in any life situation, really). You get helpful nudges like ‘take a break’ and ‘what mistakes did you make last time?’, although sadly not ‘go for a pint’.

And finally, there’s ‘Brian Eno the elusive’. Notoriously shy of interviews and dealing with banal questions with long-winded vague replies that fill the room with seemingly highbrow words – leaving the interviewer wondering what they asked in the first place, let alone whether he actually replied – an Eno interview will leave you believing that he is simultaneously avoiding the question like he knows nothing about the subject, and looking like he just knows too much to bother answering it.

An early interview with U2’s The Edge perhaps sums him up, and says a lot about U2’s working relationship with Brian – and, also, in a rather tongue-in-cheek way tries to burst the Eno bubble that we have just spent the last few paragraphs blowing up.

“He’s not a great keyboard player, he doesn’t write great songs really, he doesn’t have the craft that, say, Bowie has to write a song, or Paul McCartney…” The Edge said to One-Two Testing magazine in 1984. “His engineering and technical abilities are limited as well. In fact, he knows very little about an awful lot, but it’s how he applies that knowledge. I suppose it’s down to confidence, too.”

Master, master

What The Edge was hinting at – and indeed, what we are discussing here – is that the Eno confidence can be applied magnificently to a host of projects, that with every collaboration, every production, every atmospheric chord change and recorded found sound, Eno can be both the match and touch paper that gets a project started or accelerates it beyond the ordinary to extraordinary.

So while The Edge might have been flirting with the idea that Brian is a jack of many trades, what we really have with Eno is the master of many, the pioneering magpie of electronic music production and so much more. Eno, whether you know what he’s doing or not, will transform your project, just as he has the musical landscape of the last 50 years.

Brian Eno in four tracks

1. David Bowie - Warszawa (1977)

Introducing the second side of Bowie’s long player Low – aka the greatest album b-side ever – Warszawa delivers stunning atmosphere but was inspired by the bleakness of the city in its title. Bowie’s ‘made-up word’ lyrics are perfect for the darkness, which is made even more oppressive with Eno’s synths: a Minimoog and the same EMS Synthi used on the track Heroes.

Eno apparently gifted the EMS to Bowie in 1998 with a note saying, “Look after it. Patch it up in strange ways – it’s surprising that it can still make noises that nothing else can make.”

2. Brian Eno - An Ending (Ascent)

Very possibly not just the best Eno track ever recorded but the finest example of electronic ambience you’ll ever be lucky enough to listen to. In a brilliant Eno-esque way, he recorded it for a documentary – For All Mankind – that didn’t see the light of day for years, and it could have been lost without trace had not both the stunning Apollo visuals and soundtrack worked so well when they joined forces. Best enjoyed late at night alongside said visuals, with what your dad used to call a ‘jazz cigarette’.

3. Passengers - Slug

Very possibly not just one of Brian Eno’s great collaborations but the best song you didn’t know by U2. In another haphazard Eno/soundtrack story, he got together with U2 to record the score to a Peter Greenaway film called The Pillow Book.

That didn’t happen but they recorded some tracks anyway, as you do, and this one, inspired by the Tokyo/Blade Runner-esque landscape, was initially called Seibu. Deemed not good enough, it was binned before that man The Edge rescued it, thank goodness, and Eno added the unforgettable synths and chords. Magical.

4. Brian Eno - Emerald and Lime

One from each of ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, and now this final choice bridges a couple of decades in the 21st century, which is not only neat, but proves Eno’s longevity and impact across the years.

Here he teams up with Leo Abrahams and Jon Hopkins, surely the ultimate ambient trio, bar Richard James? It could never be three times their connected power, but it’s still a wonderfully evocative highlight from the album Small Craft On A Milk Sea.