From plugging your gear in, creating your tunes, to listening back to the results, there is nothing that beats producing your own music… when everything is running smoothly, that is. When things go wrong in the studio, there can be nothing worse, nothing more soul-destroying than having a great idea and not being able to convert it into sound.

Jim Keller knows this well. After working in studios like Avatar in New York and with recording icons including Bob Clearmountain, he and his company Sondhus have become the go-to studio problem-solvers for the likes of Depeche Mode’s Martin Gore and the distinguished Juilliard School in New York. Incredibly different projects but with the same goal: to make a space that is comfortable, creative and inspiring for music making.

Changing spaces...

Jim Keller comes from a family of builders, but has always had a fascination with recording studios and electronics, not to mention a love for listening to and recording music. Building recording studios, then, seemed like the obvious career move. But at a time where many large pro recording studios face budget cuts as record companies rely more on streaming than physical sales, designing studios might have a limited scope in terms of a business, right? Wrong.

It turns out that the small-to-medium project studio business is thriving, as bands take their record contract advances and create spaces at home, so Jim’s Sondhus business is also booming as he helps them convert what might be a spare space at home into a pro setup.

Jim also has some top tips for all MusicRadar readers on how to convert whatever space you use – from garage to bedroom – into an inspiring and rewarding space. But first, let’s discover how he creates some of the most incredible-sounding and -looking recording spaces in the world – and more importantly, drool over some pictures of them.

You come from a background of builders, so how did you move into the world of recording studios?

“I had a big passion for music growing up and also for electronics, so knew I wanted to work in studios. I hung out in local recording spaces in Ohio, then moved to LA and worked as a tech at Apogee Electronics, learning a lot of technical things there. The company is owned by Betty Bennett who is married to Bob Clearmountain, and I got to work with him one summer.

“Then I moved to New York and worked at Avatar Studios which was [and now is again] Power Station. I was really lucky to land there; an old school studio with an unbelievable history. I worked with Rich Costey [Foo Fighters, Korn, Muse and many more] for years. Importantly, I also helped design and build Studio G there.

“Then I went off making records alone, and built two or three studios for myself in New York, and then got really into acoustics. Friends would ask me to help build rooms, then friends of friends, and by 2010, I thought ‘this is turning into a thing!’ Sondhus began, and the projects got more sophisticated. We’re now 13 years in with nine people: builders, design nerds but all musicians.”

Rather than big recording studios, you specialise in creating more bespoke studios at home, right?

“Yes, the rooms that we do are custom-tailored studios mostly for private homes. I saw the writing on the wall, making records with bands as the budgets were getting lower. Big studios were closing, but all the bands, producers and songwriters I knew were putting their own setups together and building nice studios so I saw it as a new market.

“A lot of bands now take their advance and build studios themselves. Musicians are naturally creative, so they’re thinking ‘OK, if we have this chunk of money, we can spend it on a studio or Pro Tools rig with mics’, and so on. That’s great. I love big commercial studios but also love going to a home studio – that atmosphere can be comfortable and also inspiring. Big studios are still awesome, but I think that you can put together a studio at home and make a record that sounds competitive plus the affordability is amazing.”

Is there an overall goal you have with a studio build or conversion?

“It’s to make a space comfortable and make it inspiring. You spend a lot of time in the studio so it has to feel right. I know from working in big studios that 14 hours a day in a studio without windows sucks; it drains you and there’s nothing inspiring. When we have the opportunity to have natural light, we keep it at all costs.”

What were some of the first high profile projects you took on?

“The first one that solidified the idea into a business was for Paul Waaktaar-Savoy who is the guitarist and songwriter for a-ha. We built a studio for him in New York. It was the first time we had a decent budget and he has great taste aesthetically, and also the first time I felt that my vision for Sondhus was sealed: that the room looked and sounded great.”

We’re guessing there isn’t a typical process as each project is different?

“There are a few key points to discover early on: what makes them [the artist or producer] tick; what do they like, not just in music or interior design, but in fashion, in paintings and photography, something that paints a picture of who they are. It might not translate into the finished design, but it’s trying to make a space where somebody sits down and can feel comfortable and inspired.

“Another crucial one is workflow. One of the projects I am most proud of was where we did no acoustic work. It was all about workflow, planning out the space and designing somewhere where the artist didn’t have to think too much or look for things – everything was set up so they could just capture that idea immediately. From my days of making records, [I know] you can have a great idea, but if you are fumbling about trying to find a connector or where you plug in your headphones, that great idea can get lost really quickly.”

Getting the bass to respond in a linear fashion is a common problem

What are the most common technical issues you face?

“One is that a lot of people have a lot of gear: drum machines, synths, modules, keyboards, controllers, all over the place. How do you make space for all that? How do you use that keyboard that has been sitting on the shelf for a year? Where do you plug it in? [Without] digging through boxes trying to find the power supply. We designed a really elaborate power supply for one client who had hundreds of modules and boxes of wall warts.

“It was a universal power supply with a database and switches so you just selected the gear and it automatically outputs the right voltage. The other technical problem is low frequency linearity. It is a problem mostly in residential studios where the room is built and you can’t change the height/width/depth ratio. Getting the bass to respond in a linear fashion is a common problem.”

How did it work with Depeche Mode and their studio spaces?

“I felt really lucky and honoured to have met those guys as I was a huge Depeche fan as a kid. A friend of mine was working with Dave Gahan, the singer, so I first built a room for him in NYC, nothing huge, nothing crazy, a fairly modest place; a song-writing and vocal recording space.

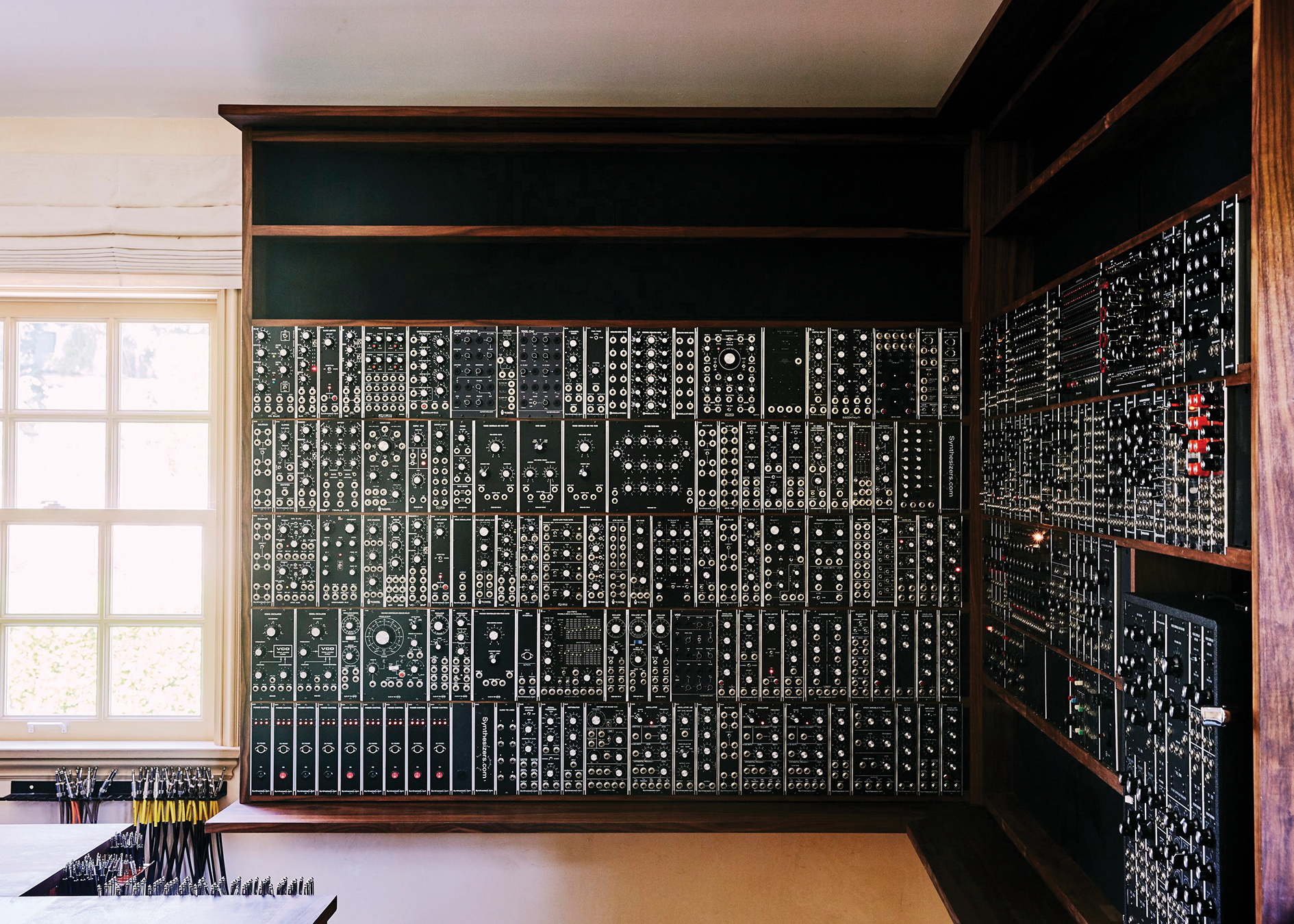

“A few years after that Martin Gore reached out because he had an existing studio in California with the most equipment that I have ever seen of anybody’s collection. There is the main recording room with every synth you can imagine and huge modular setups. There’s another room with keyboards and another which is storage, with all kinds of old stuff that’s pulled out once in a while.

“When we did that project for Martin it was all workflow, technical solutions, custom furniture, custom built Eurorack, like one entire wall is all Eurorack. It was all custom made: the cabinets, power distribution, the rails for the Eurorack, we built everything. I think there were 1,100 modules and counting! It’s funny because as we were building it, every day a few more modules would show up, so we thought, ‘OK, we should future-proof this’, so we built in about 15% extra blank space. That was 2017 so I’m sure it’s full now!

“Martin and Dave are just excellent people and visionary, of course. Being able to help them, to offer a solution [was a huge honour]. It’s not like we’re helping make the record but I like to think that it might help clear their path a little.”

What has been your favourite project?

“The Juilliard School in Manhattan – it was a big next step for us. The school had an original studio since 1969 but not really the studio that the facility deserved so it was a gut renovation. There are a number of things we absolutely nailed, like all the work had to be done in the three months while the school was out [on summer recess].

“We did all the design, construction, and managing, but the thing I liked most about that project was that it gave us the chance to build an incredible sounding, huge live room. The students at the school, with the music they play – chamber music and jazz – need that kind of space, so the opportunity to design something with a big room and with a controlled, beautiful sonic fingerprint, that is rare these days. So we were really excited to do that.”

Jim Keller’s top six Sondhus tips to create your own studio space on a budget

1. “Organisation is a big one for me, just knowing where gear is. It might sound like a no brainer, but if you have a lot of gear it is essential that it is organised. That is always how I rate my studios, to be able to move quickly and be able to find things with ease.”

2. “Getting a creative space without worrying about neighbours is important, so sound isolation is key. However, it can be the hardest problem to solve and can also be expensive, so is often a large part of the cost for projects that we do. It can be tricky, but acoustic door seals are relatively inexpensive and can go a long way to not letting the sound in or out.”

3. “As far as acoustics go, it is nice to have a space with a short decay time so you can hear the music more clearly, to hear what is coming out of the speakers and not hear the room. The low end aside, the acoustics for that kind of studio are very easy. I would say forget going for low-frequency linearity in your room because you will most likely have low-frequency issues. Some bass notes will tend to disappear or some will sound 10dB hotter. Those are room modes that you can fix – we have solutions, but it can be slightly on the time-consuming side.”

4. “One option for the low end is to get a great pair of headphones and learn them really well. If you need to make a mix decision around the low-frequency range, turn your speakers down and get your headphones on and you should get to know pretty quickly where everything is sitting in the track. It’s kind of like where you print the rough mix and go out in the car and listen.”

5. “High frequency absorption is super easy. You don’t need a ton of it as you don’t want to suck everything out of the room, but basically you treat your first reflection points first which is great for monitoring. You can get standard acoustic panels, super cheap for this and I would say to cover about 20% of the surface so that you’re just controlling that decay time a little. If you focus on the first reflection point then everything will instantly sound better and you’ll be able to make decisions faster.”

6. “Finally, sometimes just ignore the hard and fast rules of acoustics in favour of natural light!”