At first glance, there is no particular reason for a four-part documentary about Bernie Madoff to come out in 2023. The fraudster and financier has been dead for two years. His Ponzi scheme unraveled 14 years ago. Efforts to repay victims of his fraud are ongoing. Why revisit this particular saga now?

Three days before Joe Berlinger, the director of Netflix’s new documentary Madoff: The Monster of Wall Street, and I are scheduled to talk, the news cycle provides the perfect answer. Sam Bankman-Fried, the 30-year-old founder and CEO of the cryptocurrency exchange FTX, is arrested in the Bahamas. The next day, he is indicted on eight criminal counts, on charges including wire fraud, conspiracy to commit money laundering, and conspiracy to commit securities fraud.

Unlike Madoff, Bankman-Fried hasn’t been accused of running a Ponzi scheme. But following his arrest, multiple news outlets have drawn comparisons between the two. Bankman-Fried allegedly ran a “wide-ranging scheme” to “misappropriate billions of dollars of customer funds” and “mislead investors”, per the Department of Justice. The scope of the alleged fraud is reminiscent of Madoff’s own operation, as is the mystique that once surrounded both men. Bankman-Fried, The New York Times noted, “was once described as a modern-day John Pierpont Morgan, and became a darling of big investors in Silicon Valley.” Madoff, meanwhile, had earned investors’ trust and was once “considered so innovative and successful that wealthy individuals and blue-chip firms sought his investment services and advice,” ABC News wrote at the time of his downfall. As the case against Bankman-Fried progresses, we will find out if comparisons with Madoff were justified or not.

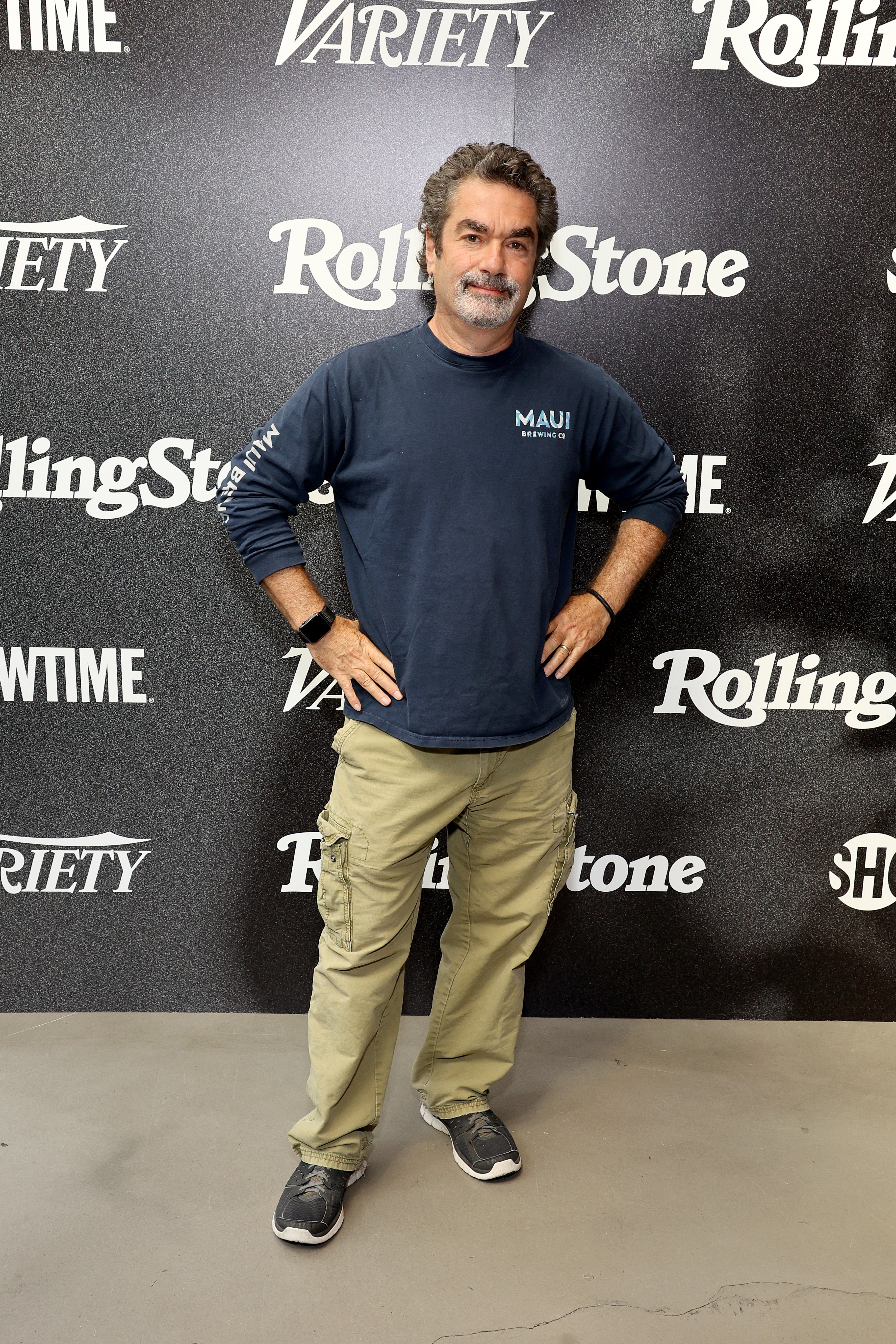

Berlinger, one of the foremost true-crime documentary directors, came to the Madoff story by way of Netflix. His previous credits include the Paradise Lost trilogy about the West Memphis three and Crude, a standalone about a class-action lawsuit against the energy corporation Chevron. When Netflix brought up the possibility of a Madoff documentary, Berlinger had just wrapped up a string of documentaries dedicated to various serial killers. Since 2019, his releases have tackled Ted Bundy, Samuel Little, John Wayne Gacy, and Jeffrey Dahmer. Berlinger was, by his own admission, “a little serial-killered out.”

“I’ve done a lot of serial killer shows in a row, and that has an emotional toll,” he tells The Independent in a video call in December. “I love true crime, obviously. And I think the idea behind [this documentary] was, ‘Let’s broaden our palette on crime.’”

A self-described “stock market geek”, Berlinger was itching to produce a show that would not only delve into the human side of things, but also into the technical aspects of Madoff’s fraud. “Little did I know that this FTX thing would happen,” he says, describing this latest situation as “a perfect analogy” to show that key lessons of the Madoff era have not been learned.

Bernie Madoff came of age at a time when America, recovering from the trauma of World War II, hungered “for quiet, for peace, for normality,” Diana B Henriques, the author of The Wizard of Lies: Bernie Madoff and The Death of Trust, says in the documentary. He grew up partly in a middle-class neighbourhood in Queens, but his parents experienced financial difficulties. A tax lien was put on their house. His mother, initially a homemaker, had to find work.

“This was not how the successful suburban family was supposed to operate,” Henriques says in the series. “And it instilled in Madoff an absolute non-negotiable requirement to succeed. … What he wanted was the fast, flamboyant success of Wall Street.”

What Madoff found instead is a story well-known by now. It is so brazen it fits in a few words: he presented himself as a money manager who would take his clients’ money and invest it. But Madoff did not invest the money. Instead, when clients asked to withdraw funds, he used other clients’ money to pay them.

“It was all a fraud,” Bruce Dubinsky, a fraud examiner and forensics accountant says in the documentary. “Madoff never did any investing for his investment advisory business. It involved simply taking people’s money, telling them he was going to invest their money – and he never did. They were fictitious trades. It was a Ponzi.”

Madoff’s scheme came tumbling down in November 2008. Money ran out; his sons Mark and Andrew alerted authorities. Madoff was arrested in December of that year. He pleaded guilty in 2009 to multiple felonies and was sentenced to 150 years in prison. In 2020, Madoff asked for compassionate release citing his ailing health. A federal judge denied that request, and Madoff died in prison the following year at the age of 82.

When I ask Berlinger whether he thinks Madoff should have been allowed to live his final days out of prison, he replies negatively. “He spent most of his life living the life that most people only dream of,” he says. Judge Denny Chin, who denied Madoff’s request for compassionate release, said that Madoff was “never truly remorseful” for his actions.

To Berlinger, a “financial serial killer” like Madoff shares a characteristic with the serial killers whose gruesome crimes Berlinger has documented on the screen: “They clearly lack empathy.” “Nobody who has empathy can do what Bundy, Gacy, or Dahmer did, or what Madoff did,” Berlinger says. “That’s the catch-22: I don’t think they’re capable of remorse, because they lack empathy.”

White-collar crimes can be hard to discuss in concrete terms. They take place in the immaterial realm of financial transactions and shoddy business dealings. Evidence is often found in documents and databases. Remedies include regulation and governmental oversight. Madoff: The Monster of Wall Street is part of a movement in true crime that has cast a new eye on white-collar crimes. Recent releases have endeavored to tell them as real-world crime stories, involving a significant amount of victimization and impacting the lives of individuals. TV shows and podcasts about the Theranos case highlighted the consequences of Elizabeth Holmes’s fraud on cancer patients who relied on the company’s faulty tests. They also delved into the tragic fate of Ian Gibbons, a former Theranos employee who died by suicide. The podcast You’re Wrong About has devoted several episodes to cases of corporate malfeasance.

Madoff: The Monster of Wall Street includes interviews with Gordon Bennett and Kate Carolan, a couple who trusted Madoff with their retirement savings. They emerge as the victims of not just Madoff himself, but of a system that failed them repeatedly when it failed to detect Madoff’s fraud multiple times.

“It was very important to tell those victims’ stories, and to remind people that these financial white-collar crimes do have victims where lives were absolutely destroyed,” Berlinger says. “At the beginning of the show, we call him a financial serial killer, because that’s how I view him. I mean, he just destroyed the lives of many.”

Berlinger sees a parallel between the double life of a fraudster like Madoff, capable of presenting himself like a skilled businessman while running a business he knows is bogus, and that of a serial killer who manages to lead a secret life of crime. “I think somewhere they obviously know they’re doing something wrong, because they’re covering their tracks. But I think somehow they all think it’s all going to work out, and they build up these justifications and they’re not dealing rationally with reality,” he says. “Which, to me, is a similarity to serial killers. They live in their own world of fantasy.”

Madoff: The Monster of Wall Street is at its most damning when it looks back on missed opportunities to stop Madoff. The SEC “gave him a clean bill of health” on several occasions, Berlinger says. Per Fortune, “after [Madoff’s fraud] was exposed in December 2008, a shaken SEC scrambled to put controls in place to prevent such episodes from recurring and uncover them early.” Whatever controls were put into place haven’t prevented history from seemingly repeating itself in the cryptocurrency space, as evidenced by the collapse of FTX.

“It’s absurd. It’s scary, the lack of oversight,” Berlinger says. “Crypto hasn’t been regulated properly and the SEC failed miserably at its job again. And the SEC failed miserably at its job during the [2008] financial crisis.”

This is a familiar story to Berlinger. His past work, he points out, has looked into wrongful convictions, FBI corruption in the Whitey Bulger case, and polluting corporations. “Institutional failure has been much more of a theme of my work than the little departure I took with the serial killer stuff,” he says. “So I would say Madoff actually fits more in with what I’ve done over the years than Bundy.”

In Madoff’s absence, Berlinger conjures up his subject’s voice and psyche through experts, audio tapes of Madoff, and dramatic reconstructions. When I ask Berlinger what he would have wanted to ask Madoff, had his subject still been alive, Berlinger points to Madoff’s family, specifically his sons Andrew and Mark. Both worked for their father, but in a part of the business unrelated to the Ponzi scheme.

“I do believe the family was in the dark. However, I don’t wanna completely let the boys, Andrew Mark, off the hook,” Berlinger adds. “I think they didn’t know what was going on, but they had to have known something was amiss. And as financial professionals, they kind of owed it to themselves to dig a little deeper. … But I do believe they were largely in the dark and trusted their father. So I would want to [ask Bernie]: How could you do that to your own children? Because it wasn’t going to have a good ending.”