Richard James Burgess is very much the unsung superhero of music production and innovation. He coined the phrase New Romantic while hanging out with the likes of Rusty Egan at The Blitz club in the late '70s, before producing two gold (“Gold!”) albums for the movement's poster boys, Spandau Ballet.

As if naming one music movement wasn't enough, Burgess then came up with the term Electronic Dance Music, or EDM, in the '80s for his band Landscape, for which he also produced the first ever computer-driven hit record with Einstein A Go-Go. Then there was the another 'first-ever', that of the use of commercial sampling with Visage and Kate Bush, not to mention his invention of the electronic drum kit with the Simmons SDS-V.

To put a tick next to a single one of these accomplishments would be more than enough for most of us, but to have achieved so much, Burgess has almost become the Forrest Gump of music production. Indeed, you suspect that he might appear in the fringes of black and white footage of every major musical innovation because, yes, he is that music gear demonstrator who has been on Tomorrow's World three times.

We sat down with Burgess to discuss this extraordinary – and we don't use that word lightly – career. But where to start? Well, why not lazily get him to attempt to sum up it up?

Hello Richard! From inventing genre labels to electronic drums, producing top acts to the first computer-based tune and commercial sample, that is quite a career! What have been your highlights?

“Some were relatively small things but essential steps. Being offered the gig in the Quincy Conserve in New Zealand in late 1970 launched my career as a studio musician. Playing all those hours with great musicians, and hanging out in the best studio in NZ at the time was exhilarating.

“Getting into Berklee College of Music was a high point, and attending the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London. Playing hundreds of live gigs with Landscape was my musical high-spot, and my production career was launched when Spandau Ballet asked me to produce their first album. That was a lucky break as was knowing the great DJ, Rusty Egan, who first invited me to the Blitz.

Although we knew this was game-changing we could not have predicted where sampling would take us

“Figuring out that we could make records using a computer was an intense buzz, solving the conundrum of how to build an electronic drum-set was incredibly satisfying, and then watching them become ubiquitous through the eighties was mind-blowing. Recording live samples with Kate Bush and Jon Kelly was a pinch-yourself moment – we were figuring it out as we went along, and although we knew this was game-changing we could not have predicted where sampling would take us.”

“Lowlights have been when a record I believed in didn’t get the attention that it deserved from the record label. Any industry that can produce great wealth fosters greed and dishonesty. Getting through those situations can be ugly, and it usually comes from someone you are not expecting. I used to tell my kids that the devil arrives with a friendly handshake and a fat check.”

You recorded the first computer-generated song with Landscape's Einstein A Go-Go. What are your memories from that period?

“That was an incredibly exciting time. We had made the first eponymously-titled album for RCA records and nothing much happened. We were about to make the second album, and were experimenting with the Roland MC-8 MicroComposer. John [Walters, Landscape band mate] had the Einstein A Go-Go melody that he played on the Lyricon. He wrote the very odd drum part and we got the title from a card that John Warwicker (our designer) had sent to John. I had suggested that we add vocals because it was clear that RCA had no clue what to do with an instrumental.

“We always strove to make something original, so far as to reject anything that was reminiscent of another piece of music or band. With Einstein, I remember saying to John that we should make it as cartoon-like as possible to contrast with the extremely dark subject matter.

The funny thing is that when the record came out, nobody seemed to pick up on the fact that it was a protest song

“We had been out at Peter Gabriel’s house talking about the Fairlight CMI and he played us some of his new album. I was struck by the first-person perspective on his song The Intruder. Originally, we wrote 'Einstein said that E=MC squared', but we changed that to 'Albert said' to give it a lighter weight feel, but the verses are in the first-person.

“The funny thing is that when the record came out, nobody seemed to pick up on the fact that it was a protest song – an anti-war, anti-nuke, anti-religious fundamentalism song. We successfully dressed up the dark malevolence of the lyrics with the zaniness of the production and the instrumental melody. We did realize early on that the song had pop potential and we played up the poppy elements in the production. Having said that, it’s still a weird piece of music.”

How did your invention of the electronic drum kit come about?

“I had bought my first synthesizer in the early '70s, the EMS Synthi A (suitcase version of the classic VCS3). I was just interested in creating drum and percussion sounds. Since I was in studios playing drums, I was struck by the fact that recorded drums don’t sound much like acoustic drums do in the room – recorded drums are highly processed.

None of the drum manufacturers were interested. One said to me that drummers will never be able to figure out the wires and the knobs

“I felt that an electronic drum could be much bigger sounding than an acoustic, and was puzzled by the fact that most other instruments were electrified (the guitar had been for more than three decades by then). I experimented with all the electronic percussion devices on the market at that time, including SynDrums, the Synare, and Impakt Percussion. None did what I wanted so I made my own.”

And that eventually became the Simmons electronic drum kit, the first proper electronic alternative to real drums…

“Initially none of the drum manufacturers were interested. One said to me that drummers will never be able to figure out the wires and the knobs. Eventually, I demonstrated my concept to Dave Simmons on an ARP 2600 and the rest is history. Because we had been working with the MC-8 we figured out that we could trigger what became the SDS-V from that.

“I made the Shock records and Landscape’s Tearooms of Mars album using the prototype SDS-V drum synth triggered from our MC-8. The first recording with the SDS-V being played live by a drummer is Chant No.1 by Spandau Ballet, with John Keeble playing.”

Talking of Spandau Ballet, you produced two gold albums and seven hit singles with them. Was record production something you aimed for or fell into?

“I would describe it as a slow-growing, long-standing obsession. From being a child, I always wondered how records were put together. When I was doing session work at HMV studios in NZ, I would always stay behind and sit in the back of the control room to take in what was going on.

When I was doing studio work in London, I had the good fortune of being in the studio with many of the greatest producers and engineers of all time

“Likewise, when I was doing studio work in London, I had the good fortune of being in the studio with many of the greatest producers and engineers of all time. I would wait for a break and ask questions about the technology and what they were thinking. By the time I got to do it myself, I had learned a lot.

“Of course, this was long before personal computers, laptops, DAWs, YouTube or any kind of home recording equipment that would teach you anything meaningful. I felt very lucky to be in the most amazing studios in the world with the best producers and engineers as my teachers and mentors – although unwittingly so on their parts.”

You have seen an explosion in music-making and recording technology since Landscape, including sampling, MIDI, hard disk recording, and softsynths? What has been the good, the bad and the ugly?

“I am infatuated with technology and societal progress through the implementation of it. Technology is a more sophisticated word for a tool and the important thing about technology is what it can help us create that benefits human beings. The MC-8 was such a giant leap forward for music production and all thanks to Roland founder Kakehashi for recognizing the potential of Ralph Dyck’s original concept, and not only expanding on it but manufacturing something so esoteric and laborious to use, with very limited commercial potential.

“To me, MIDI was a natural extension of the revolution that the MC-8 started. It enabled us to link previously incompatible devices together to make even more extraordinary sounds. What Dave Smith and Kakehashi did in releasing MIDI with no royalty requirement was very generous, and very much the opposite of the walled-garden approach that many technology companies still favour.

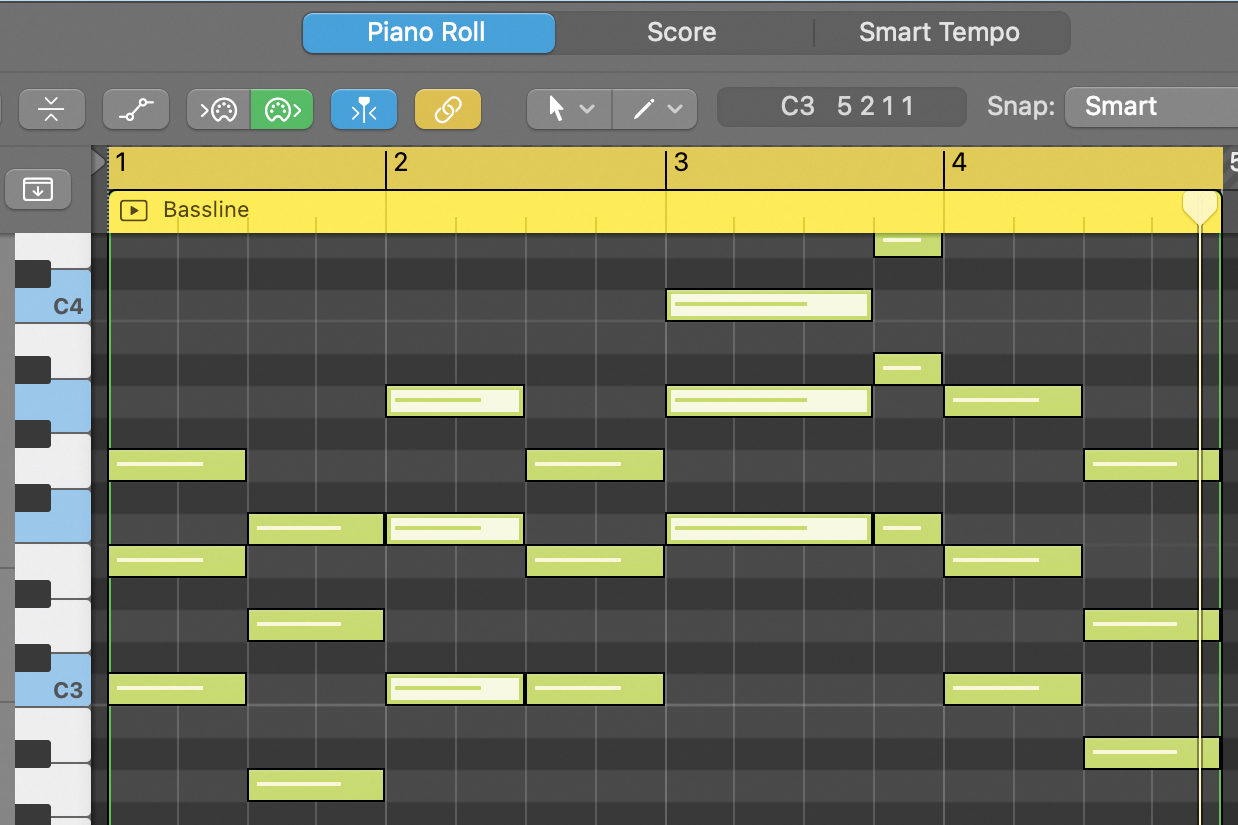

“I have the soft synth discussion often. I still have a comprehensive rack of hard synths, but I prefer to use soft synths mostly because staying in-the-box enables me to work on planes and pick up where I left off months and years later. That is more valuable to me than a perceived difference in sound quality. And two synths of the same model very often sound different anyway, depending on vintage and condition.”

What about future technology and the increased use of AI in music?

“I don’t see the drawbacks to moving forward with technology. The worst thing we can do is resist. As I see it, technology itself is neutral, it’s the application of it, the business models we attach to the use of it, and, in the case of IP, the relationship to copyright that can create problems for human creators.

“Obviously, there are many ways that AI can be abused but it’s also the greatest tool that humanity has invented to date. If books and the printing press enabled us to capture all knowledge, AI potentially enables us to interrogate and instantly access that knowledge for almost any application. That’s a major brain extension.”

You are credited with coming up with the phrase New Romantic, and also EDM, two names that have dominated large portions of our music history. Can you reveal a little more on the origins of these?

“The 'New Romantic' name came about less because of the sound of the music and more because of the look of the clothing at that time – the ruffles and the dandyish aspects of that phase of the Blitz club. I know Adam Ant (who was actually part of the post 1976 British punk movement) got very annoyed about being tagged as a 'New Romantic' in the U.S. but by then he had adopted that fashion style, and the Americans were behind the Europeans in moving into electronic new wave music.

“EDM came about through a very conscious process of trying to come up with a name that would describe our [Landscape's] music and the wider movement that was beginning to coalesce. We tossed a lot of ideas around and in the end EDM stuck. We gave our [1980 Landscape] single European Man the catalogue number EDM1 and on the back cover we said, 'EDM: Electronic Dance Music… computer programmed to perfection for your listening pleasure.' My feeling at the time was that it is better to be part of a movement otherwise you are an anomaly - which we kind of were. Our music doesn’t bear much resemblance to modern EDM, but the Model T Ford doesn’t look much like a Tesla either.

“We had a huge following as a live band, and we influenced the way other people made records during that period and since. I remember standing up at the Roland Christmas party just after we had recorded the Tearooms… album and I said that 'one day all records will be made this way'. I got off the stage and I felt like I might have overstated it a bit, but that prediction did come true. We happened to be in the right place, at the right time, with the right mindset.”

You are very much involved in the music business side of things now. Do you still get to dabble in rock n roll and electronic pop. If not, do you miss it?

“I have a ton of pieces on my laptop and various drives that I have worked on over the past couple of decades. I miss some aspects of that life, but the music business has changed so much. I felt that my time and expertise would be better applied to trying to get us back on track from the disruption that led to the massive upsurge in digital piracy and the general diversion of revenues away from artists, composers, and musicians and into the pockets of middle people. My Ph.D. dissertation was called Structural Change in the Music Industry: The Evolving Role of the Musician.

“I was a big fan of streaming from the beginning – being able to listen to anything from anywhere, at any time is amazing. At the same time, I am disturbed by how difficult it is for young musicians to make a living from recorded music now. There are some artists doing extremely well from streaming, but it is undeniable that there is less money being generated by the recorded music industry today than there was in 1999, despite a great deal more music being listened to. I like change, but if we care about musical culture, we must figure out how to make sure that we don’t undercut the creative process by the diversion of the value of recorded music.”

Having certainly been there and done that, what advice would you have, then, for anyone wanting to make a career out of music production?

“I am deeply concerned about that. Digital technology has democratized the process of making music. Streaming has democratized distribution, which is good because you don’t have to beg someone to release your music. Social media/UGC platforms have democratized marketing, which means artists and producers can break through without spending a fortune. But all this has led to 120,000 tracks a day being uploaded to the streaming services. That means the pie is being divided in many more ways than it used to be.

The one thing that hasn’t changed in the digital era is that for anyone to make a living from recorded or live music, you have to build a fanbase

“The one thing that hasn’t changed in the digital era is that for anyone to make a living from recorded or live music, you have to build a fanbase and you have to be able to stay in touch with that fanbase. The methodologies are different today, but it's the same reality whether you do it by playing gigs and manually collecting email addresses or by digital marketing. There are many incredible digital tools that can assist in this process, but that means you have to learn to use them, and you have to use them.

“Success takes a village and there are very few artists out there who can achieve national or international success without a team. That team might be a group of friends, or it might be a label or a management company. Figure out what skills you are missing and find the team or team members who have them.”