A YouGov poll has put Reform UK ahead of the Conservatives for the first time. After a terrible few weeks of election campaigning, the Tories are on 18% while Reform has edged ahead to 19%. The same poll gave Labour 37% and the Liberal Democrats 14%.

This news makes a great headline, but it actually means the Conservatives and Reform are essentially neck-and-neck in the polls. This is because all surveys are subject to errors, which are commonly plus or minus 3% in a typical poll.

This happens because even a well-conducted, probability-based survey can produce results which differ from a census of all voters. If Reform hits 21% in voting intentions and the Tories remain on 18%, statistical theory shows there is a 95% chance that Nigel Farage’s party would actually be ahead in the country.

Nevertheless, it is clear that Farage’s surprise takeover as the new Reform leader, and his decision to stand as a candidate in Clacton, has boosted support for the party. Farage was helped by Rishi Sunak’s decision to leave the D-Day celebrations early, which gave him the opportunity to attack the prime minister for a lack of patriotism.

The fact that Reform has now overtaken the Conservatives in at least one poll raises the question of whether the party can beat them in the forthcoming general election. It is very unlikely to do that in terms of seats in the House of Commons – but it might be possible when it comes to vote shares.

An important thing to remember is that Reform, in its previous incarnation as the Brexit party, has already beaten the Tories in a national election in Britain. This was in the May 2019 European Parliamentary elections which are now largely forgotten. They actually temporarily destroyed the British party system.

The Brexit party came first with 29 seats in the European parliament, followed by the Liberal Democrats with 16. Labour won 10 and the Conservatives four. Such was the collapse in Conservative support that the Greens won three more seats than the Tories.

This was at the height of the turmoil over Brexit and Theresa May’s failure to get the House of Commons to agree a deal with Brussels. When my colleagues and I analysed that election in our book Brexit Britain, we concluded that: “The public mood was very sour and many voters – leavers and remainers alike – were inclined to give the major parties a ‘good kicking’.”

There are, of course, significant differences between the European elections and general elections. Turnout was always lower in the former, and the 2019 European elections were heavily focused on Brexit – in contrast, polls reveal it is now the most important issue for only 13% of the population. Brexit has faded considerably as an issue.

However, we can all recognise that the public mood is again very sour, and that the inclination to “give the major parties a good kicking” hangs heavy in the air.

Want more election coverage from The Conversation’s academic experts? Over the coming weeks, we’ll bring you informed analysis of developments in the campaign and we’ll fact check the claims being made.

Sign up for our new, weekly election newsletter, delivered every Friday throughout the campaign and beyond.

The survey analysis we conducted during the European elections showed the Brexit party did well among older voters, the relatively uneducated, those on low incomes, men and working-class voters. They were strongly in favour of leaving the EU; they liked Farage and disliked Jeremy Corbyn and May. Many of them identified with the Brexit party, even though it was a very new political brand (having only been founded in 2018).

Brexit supporters were also rather anti-establishment, opposing excessive inequality in Britain and disliking large corporations.

The YouGov poll on 2024 vote intentions shows that Reform voters have very similar characteristics to Brexit party voters in 2019. There was no support for Reform among 18- to 24-year-olds in the survey, for example – only older voters. And support for Reform is significantly higher among working-class people than middle-class people.

The most important point about support for Reform in the 2024 election is what it will do to the Conservative vote. Unfortunately, data from the 2019 election is no use to us here, because Farage stood down Reform candidates in Conservative constituencies to give the incumbent MPs who supported Brexit a clear run. Reform ended up fielding only 275 candidates across the country, so we aren’t able to use the 2019 results as a model for what might happen this year.

We can, however, look at Ukip’s performance in the 2017 general election. Ukip still exists as a party but its leadership, candidates and voters overwhelmingly moved to the Brexit party when it was founded in 2018, and subsequently to Reform. This happened in such large numbers that Ukip can effectively be considered an earlier iteration of Reform.

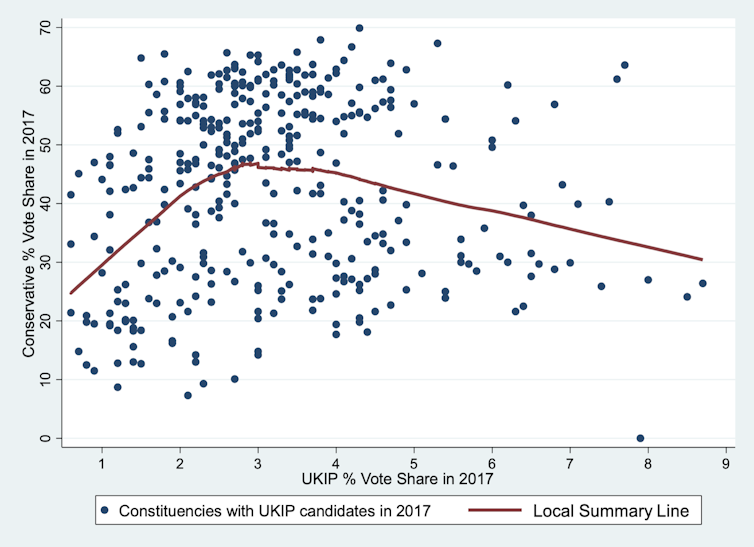

In 2017, Ukip fielded 378 candidates – close to 60% of Westminster parliamentary seats. The chart shows the relationship between the Conservative and Ukip vote shares in those seats.

Conservative and Ukip vote shares, 2017 UK election:

Each dot in the chart is a constituency and the summary line measures the relationship between the vote shares of the two parties in similar constituencies. This is not the same as fitting a summary line to all constituencies, but instead captures how the relationship changed as Ukip won more support across the country.

This reveals something very interesting – namely, that the Conservative and Ukip vote shares rose together when Ukip support remained under about 4%. In effect, the Conservatives and Ukip were allies in these constituencies, with both gaining votes from the other parties.

But the picture changed rather dramatically when Ukip began to win above that 4% threshold. Then, the parties became rivals, with Ukip making gains at the expense of the Conservatives.

The explanation for this relates to support for leave voting in the 2016 EU referendum. Leave voting was only modestly correlated with Conservative voting in 2017 (0.30), whereas it was very strongly correlated with Ukip voting (0.69). This means that many voters in the constituencies strongly favouring leave were more likely to put their trust in Ukip and Farage than the Conservatives and May to get the job done.

If Reform voters in the current election behave like Ukip voters in 2017, then the surge in support for the party will make it a strong rival to the Conservatives in practically every constituency it fights.

It is true that Brexit is no longer the salient issue it was back then, and that there is a lot of “Bregret” among voters at the present time. But a YouGov survey conducted last year showed around a third of the electorate continues to support Brexit. Coupled with the dive in support for the government, it is easy to see how disgruntled Conservative leave supporters might easily change their vote to Reform.

Ironically, this will help to deliver victories for both Labour and the Liberal Democrats in many of the seats being contested.

Paul Whiteley has received funding from the British Academy and the ESRC

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.