At noon on July 31, hundreds of devotees streamed out of the ancient Shiva temple in Nalhar village, in the Muslim-dominated district of Nuh in Haryana. They had just offered water from the Ganga, considered holy, to the shivling (a representation of Lord Shiva) in the temple, located amidst the picturesque Aravalli hills, and were set to proceed towards the Radha-Krishna temple in Singar village, around 50 kilometres away. The devotees were part of the Brijmandal Jalabhishek Yatra, a religious procession organised by the right-wing Vishva Hindu Parishad.

Soon after they began the second leg of their journey, the devotees were attacked by a mob. As stones were thrown at them, and vehicles and shops were set ablaze, the devotees ran back to the temple in terror. They sat huddled inside for five hours, as the mob surrounded the temple, which is believed by many to date back to the time of the Pandavas.

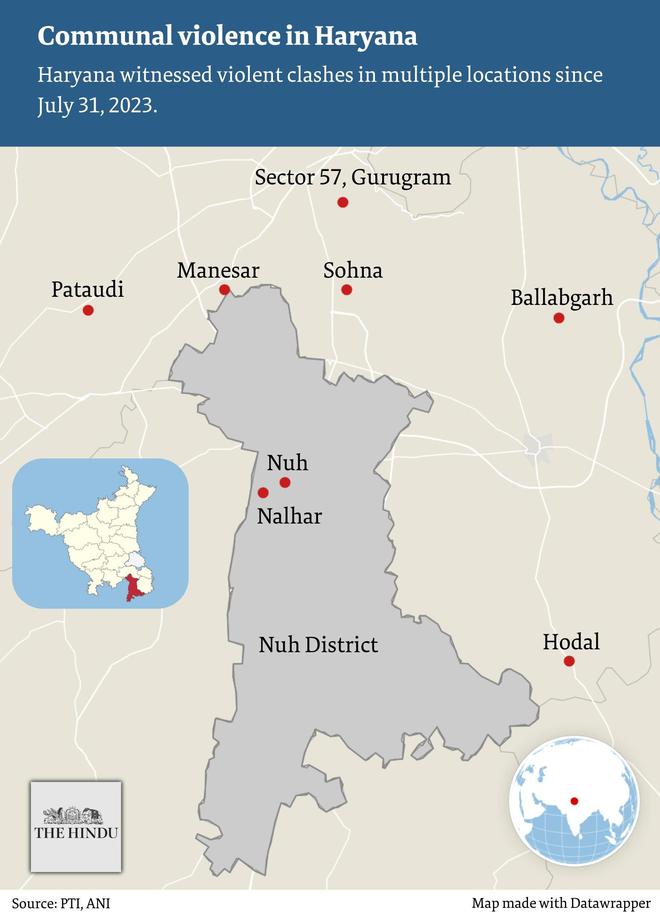

The communal clashes spilled over to the neighouring districts of Gurugram, Palwal, Faridabad, and Rewari. There were sporadic incidents of vandalism in shrines, and arson in scrap dealer shops and jhuggi-jhonpri clusters (huts and semi-permanent houses built with bricks and mud). Six people, including two Home Guards, lost their lives and 88 people were injured in the conflict. Section 144 of the Indian Penal Code (joining unlawful assembly armed with deadly weapons) was imposed in Gurugram, Palwal, and Faridabad, while a curfew was imposed in Nuh on Monday night. Internet services were suspended in these districts and all the educational institutions were shut.

While Chief Minister Manohar Lal has claimed that the situation is now under control, the suspension of mobile Internet, SMS, and dongle services in Nuh, Faridabad, Palwal, and parts of Gurugram has been extended until August 5.

Prelude to a riot

Four days after that procession turned deadly, an uneasy calm prevails in Nuh, which Niti Aayog in 2018 categorised as the most underdeveloped of India’s districts. In places where, according to a wholesale fruit seller, Shahid Hussain, Hindus and Muslims had lived together in peace for decades, broken glass, bricks, and stones lay littered on the streets now. The 20 km-long stretch from Sohna, where a mosque was vandalised by a mob the next day, to Nalhar on the Gurgaon-Alwar National Highway bears testimony to the violent clashes of July 31. Partially burnt shops, charred vehicles, and upside-down handcarts dot the once-crowded roads.

There are conflicting versions of what happened on that fateful afternoon in Nuh, which is a two-hour drive from Delhi. Ajit Singh, president of the Vishva Hindu Parishad, Gurugram, and one of the organisers of the yatra, claims that the locals threw stones on the devotees from their rooftops. He says the violence, which was unprovoked, escalated in no time: the mob set vehicles ablaze and opened fire on the devotees.

“They damaged vehicles and smashed windowpanes while we struggled to pull out women and children from the buses,” Ajit says. “The rioters later opened fire. There was negligible police presence. This was a failure of intelligence. It can also be blamed on the ineptness of the administration. The policemen, who were outnumbered by the rioters, fled the scene leaving the devotees to fend for themselves.”

Ajit says hundreds of devotees were trapped inside the shrine. “Our national joint general-secretary, Surendra Jain, was also trapped inside the temple. He kept making frantic calls to the administration. The police reached the temple around 6 p.m. By the time the administration came to our rescue, the rioters had climbed up the hillocks surrounding the temple on the three sides and fired guns,” he says.

The police were mobilised from the neighbouring districts of Faridabad, Gurugram, and Palwal to rescue the people inside the temple.

Pintu Singh, an eyewitness from Gurugram, claims that the violence broke out when six vehicles, including a black sports utility vehicle, carrying devotees reached Nuh chowk. He says there were rumours that Bajrang Dal member and self-styled gaurakshak (‘cow protector’), Monu Manesar, was inside one of them. Monu is an accused in the murder of two Muslims, Junaid and Nasir, in February in Bhiwani, Haryana.

“The vehicles had gaurakshak written on them, which is why these rumours spread,” says Pintu, 36, who sustained a shrapnel injury in the attack. Along with scores of devotees, Pintu took shelter at a women’s police station nearby.

Tension had been brewing in the region even in the run-up to the religious procession after Monu announced that he and his team would be part of it and urged people to turn up in large numbers. Muslims in the district strongly opposed his visit saying it would disturb communal harmony in the region.

According to Sharif, the former sarpanch (head of the village) of Adbar village of Nuh, another Bajrang Dal member, Bittu Bajrangi, posted provocative videos on July 31 claiming that Monu would be part of the religious procession. This, he says, proved to be the flashpoint.

“The videos of the riots show that it is mostly gullible youngsters who formed the mob, not middle-aged people. Had the administration been alert, this could have been prevented,” says Sharif while waiting for a meeting with Congress MLA Aftab Ahmed at his residence.

Shahid, the wholesale fruit seller, speaks fondly of communal harmony in the district. “We install pandals during the Kanwar Yatra (an annual pilgrimage of devotees of Shiva) every year. We are also part of the religious processions of Hindus during Dussehra. Even the VHP procession has been peaceful every year. But it was the provocation by certain people this year which vitiated the atmosphere,” he says.

The pilgrimage was a subdued affair for many years. But over the last three years, it has been held by the VHP on a large scale, with people from Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan also taking part in it. The organisers claim that 15,000 people took part this time. The yatra, they say, aims to “restore the lost glory and significance of the Mahabharat-era temples in Nuh”.

Referring to the provocative videos, Aftab says the matter was brought to the administration’s notice. “The Kanwar Yatra and Jalabhishek Yatra are annual rituals. There has never been any opposition to them. But a situation was created for a showdown this time. The administration should have taken action against the miscreants before granting permission to the procession. This was actually a show of strength in the name of a procession. The participants were brandishing weapons. While people from far-off places take part in the procession, the locals in Haryana have little clue about it,” he says.

Though the Chief Minister said that the violence was pre-meditated and part of a larger conspiracy, Deputy Chief Minister Dushyant Chautala, the leader of the Jannayak Janta Party which is in alliance with the Bharatiya Janata Party in Haryana, partially blamed the organisers. He said there was no proper estimate of the turnout, and this lapse could have led to the violence. The Leader of the Opposition, Bhupinder Singh Hooda, said the “right step at the right time” could have prevented the situation and termed it “an administrative failure”.

A tale of two districts

Despite falling in the National Capital Region, Nuh is yet to be connected by a railway network. It does not have a single university. Its health and educational infrastructure are in a shambles. Drinking and irrigation water are a challenge. The local population is mostly dependent on agriculture for their livelihood. Known for crime, mostly vehicle thefts, Nuh has been dubbed the ‘new Jamtara’, after the district in Jharkhand which has become notorious for cybercrime.

In contrast to Nuh is Gurugram, its neighbour, just a couple of minutes away from Delhi. Known as Haryana’s financial capital for making the maximum contribution to the State exchequer, Gurugram is the fastest-growing information technology and financial hub after Bengaluru and Mumbai, with the third highest per capita income in the country. It hosts 250 Fortune 500 companies. It is dotted with skyscrapers, malls, and premium dining zones.

What connected these two starkly different districts on July 31 were riots. On that evening, the violence quickly spread from Nuh to Sohna, a sub-division of Gurugram which has a considerable Muslim population. A mob set five cars, an auto-rickshaw, a shop, and four kiosks on fire. They also vandalised a mosque.

Around midnight, an armed mob attacked the Anjuman Jama Masjid in the heart of Gurugram. Imam Mohammad Saad, 26, was killed, and Khursheed, a staff member, was injured. The mob set the shrine ablaze.

Saad and his older brother Maulana Shadab had shifted to Gurugram from Bihar’s Sitamarhi only seven months ago in search of livelihood. They stayed separately. Shadab, a private tutor in Gurugram, recalls that he had spoken to his brother just before the attack. Saad had told him that he was safe since the police had been deployed outside the mosque. “Just minutes later, the attack took place. I got a call from a friend around 2 a.m. saying Saad was injured and admitted to hospital. But I learned later that he had died on the spot,” says Shadab. “Saad would post songs on his Instagram account promoting communal harmony. He would have never thought that he himself would become a victim of hatred one day.”

This audacious attack in an upmarket area with gated condos and steel-and-glass office buildings, located close to a golf course, left the residents shocked. Panic spread across Gurugram’s corporate offices and gated colonies. Fake news that inflated the numbers killed did the rounds on WhatsApp. Colleagues expressed concern about their Muslim co-workers. Most workplaces asked employees to go home; malls closed earlier than usual; and many households wondered about the safety of their help. But the conversations also divided teams and neighbours into “us” and “them”.

Altaf Ahmad, co-founder of the Gurgaon Nagrik Ekta Manch, a civil society group, says it was simply “unthinkable” that a mosque in the middle of Gurugram had been attacked. He describes the situation as a “new low”. Dozens of people, including businessmen, have returned to their native places after this attack, says Altaf.

Several shops, mostly salons run by Muslims, have been shut since the riots broke out. Given the climate of fear, daily wage earners, domestic workers, and fruit sellers from the community have all fled to their native homes.

Editorial | Making a riot: On the communal clashes in Haryana

At night, Gurugram lived its lie. The bright lights of the city did not dim. In Nuh, meanwhile, people padlocked their doors and hid inside their own homes.

A growing distrust

Nuh is now limping back to normalcy with the administration relaxing the curfew on August 2 and 3. Educational institutions in Gurugram and other districts have been opened. But in an indication of the growing distrust between the two communities, the Hindu outfits in Gurugram have given the administration a week’s ultimatum to ban Friday’s Jumma Namaz in open spaces in the city. The Nuh Police, too, have advised Muslim clerics to avoid offering prayers in the open on Friday. The Gurugram Imam Sangathan has also decided not to offer prayers in the open.

The communal divide in south Haryana between Nuh, which is part of the larger Mewat region, a term for the Meo-Muslim dominated areas of Rajasthan, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, and the Ahirwal- and Gurjar-dominated belt spread across Faridabad, Palwal, Gurugram, Rewari, and Mahendragarh has existed for long. While there have been minor confrontations between the two communities, triggered by incidents such as suspicions of cow slaughter, hate speeches and lynchings have been taking place more and more in the last few years.

Hindu majoritarian outfits and resident welfare associations have sporadically protested against the Friday namaz in open spaces in Gurugram in the last few years. From 2018 onwards, at the behest of Hindu outfits, open spaces where congregational namaz could be offered have come down from 116 to six. Hindu outfits have also been protesting against meat shops, which are mostly owned by the minority community, during the Navaratri festival every year for the past five years. Meat shops in the city are not allowed to open on Tuesdays. There have also been several instances of attacks on Muslims in and around Gurugram. In 2021, a Christmas carnival in a private school in Pataudi area was disrupted by a mob. Right-wing Hindu outfits also held a mahapanchayat in Pataudi two years ago, and openly called for violence against the religious minority.

“Over the years, right-wing groups have been active in and around Gurugram and constantly keep the atmosphere communally charged,” says Altaf. “In each of these situations, the first step is to provoke Muslims by either attacking them or offending their religion to a point where a confrontation takes place,” he says. “This was the case in Nuh too.”