The King Of Calypso is about as frivolous and inappropriate a moniker for Harry Belafonte as possible. With the calypso and hits like “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)” in the Fifties, he certainly attained international success and highly advantageous financial muscle, but Belafonte never felt comfortable with that unsolicited soubriquet.

In reality, Belafonte was America’s first black superstar, with a flourishing career as actor, singer, entertainer, producer and performer that lasted more than half a century. Belafonte achieved an extraordinary number of firsts: he was the first artist to sell more than a million LPs; the first black man to win an Emmy; the first Afro-American television producer.

These debuts were all accomplished in the Fifties, a time when white America was inflexible to, if not actually attempting to reverse, racial progress. But to achieve his success, Belafonte refused to appease prejudiced individuals. In fact, to some extent, Belafonte was like a Trojan horse. His good looks and sweet calypso sounds worked in his favour, allowing him to penetrate the wider, whiter public arena. But once in that space, he created some mischief – undoubtedly risking his career.

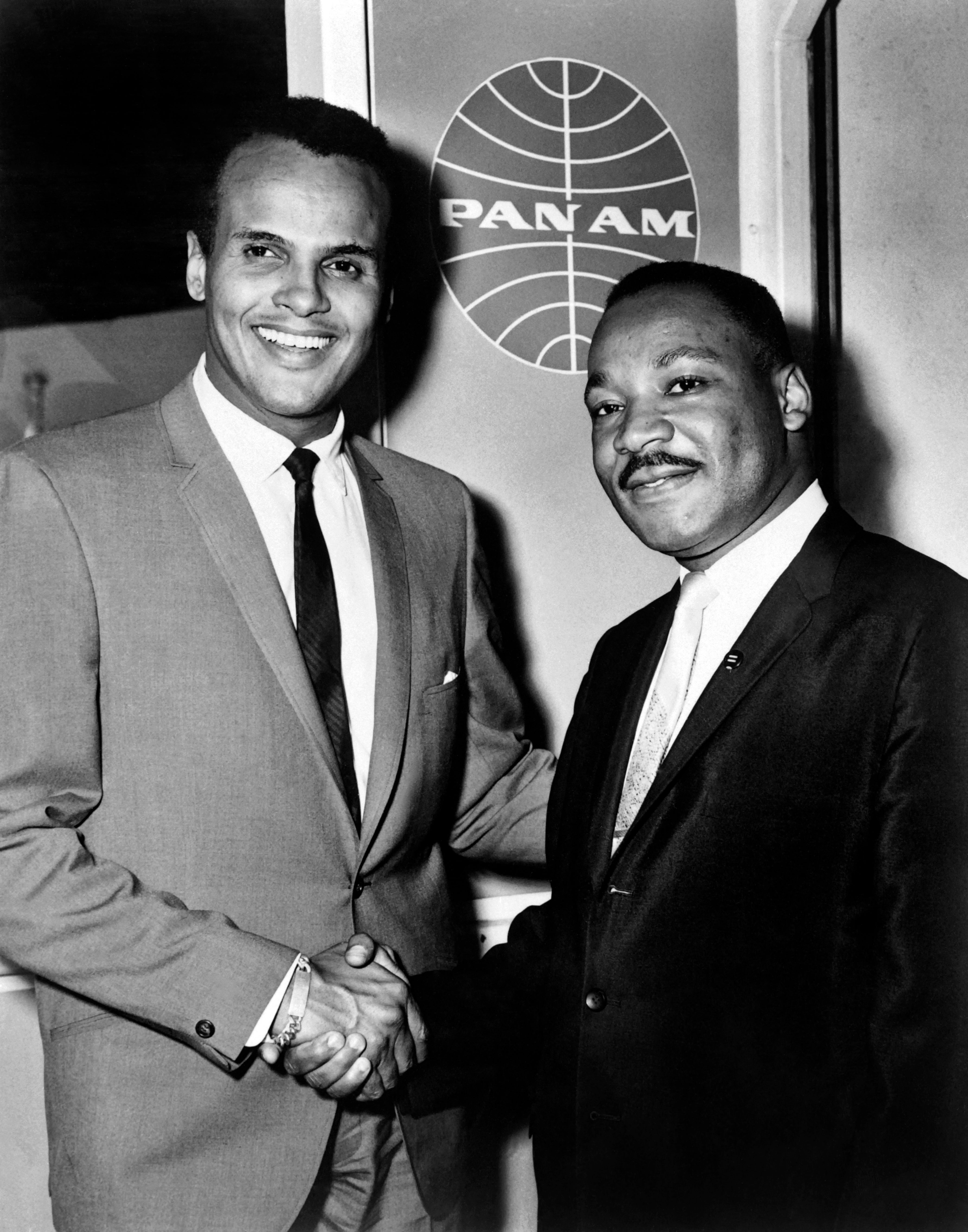

Indeed parallel to, if not often intertwined with the artistic side of his professional life, Belafonte was a courageous champion of civil rights and liberties. His activism started in a racially-splintered 1950s America when an unknown preacher called Martin Luther King Jr approached him for counsel. In the Sixties, Belafonte was close to President Kennedy and Bobby Kennedy, influencing them both. Throughout his life, Belafonte became increasingly outspoken. By 2005, at the age of 77, he infamously damned President George W Bush as “the greatest terrorist in the world”.

Harold George Bellanfanti Jr was born on 1 March 1927, in New York’s Harlem to parents of Caribbean origin. In 1935, Belafonte travelled with his mother to Jamaica. After five years on the island, mother and son returned to New York in 1939 where Belafonte attended George Washington High School. Decades later, Belafonte recalled that his mother was prepared to make “any bargain with poverty” to educate her son.

But Belafonte, who suffered from dyslexia, dropped out of high school in the early 1940s. Guilt troubled him for abandoning his education, but there were dignified motives for Belafonte’s actions: “I volunteered to be in the US navy during the Second World War, not just because it gave me relief from poverty and a place to maybe learn a skill, but because I really believed in the principles of what we fought for.” In fact, what fuelled much of his indignation and activism throughout the Fifties and Sixties was how badly black American servicemen were treated back in the States – after fighting for democracy. Following a glorious VJ Day, Belafonte was still unskilled, acquiring a lifeless job as a janitor’s assistant in New York.

Then, one day, a customer offered him a theatre ticket as a tip. Belafonte remembered: “I didn’t even know what theatre was. But I went along. It was a revelation.” Inspired, he was soon attending Erwin Piscator’s celebrated acting workshop where other future movie icons of the Fifties, like Marlon Brando, Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier, were industriously sharpening their craft. To finance these acting classes, Belafonte worked as a nightclub singer.

Throughout the late Forties, Belafonte pursued his musical and acting career simultaneously – performing with the American Negro Theatre, singing in cabarets, opening a nightclub – before finally scoring a recording contract with the Jubilee label in 1949. Although the label promoted him as a pop singer like Frank Sinatra, Belafonte was starting to investigate folk music via the Library Of Congress and also studying Caribbean music. But the unique fruits of Belafonte’s explorations – a seductive mix of pop, folk, jazz, and Caribbean styles – wouldn’t surface until the mid-Fifties.

In fact, despite the desperate shortage of major Hollywood roles for black actors, Belafonte actually hit the big time in movies before he dominated the mid-Fifties pop scene. Bright Road (1953) was his breakthrough movie. He capitalised on this film the following year with Otto Preminger’s wildly successful, Carmen Jones.

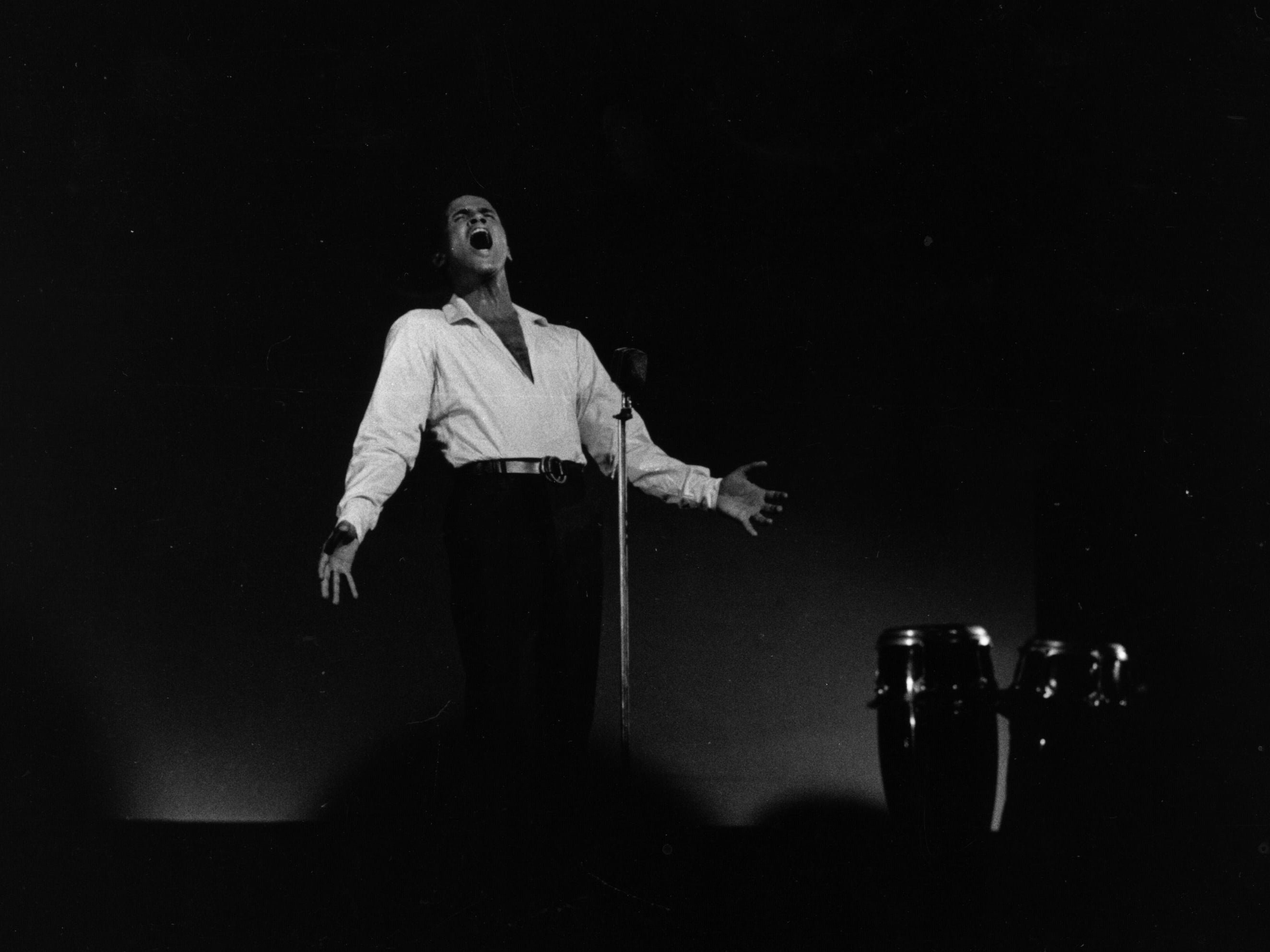

In the mid-Fifties, with his movie career skyrocketing, Belafonte’s musical ambitions also started to crystallise. Having switched to RCA Victor in 1952, Belafonte released two albums – Belafonte and Calypso – in 1956. It was the year rock’n’roll exploded across the States. The mambo was also raging and the nation was about to go calypso crazy, almost wholly due to Belafonte. Although both those albums topped the album charts, it was the latter, Calypso, which included the hits “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)” and “Jamaica Farewell”, that settled at the number one spot for an extraordinary 31 weeks.

Commenting on his mid-Fifties superstardom, Belafonte once said: “I could have made $2bn or $3bn – and ended up with some very cruel addiction – but I chose to be a civil rights warrior instead.” Indeed, he quickly demonstrated there was much more to him than pretty-boy looks and a mellifluous voice. As well as continuing to record very popular albums like Belafonte at Carnegie Hall, Belafonte refused to tour the prejudiced South and embraced thought-provoking movie roles at a time when the racial atmosphere in America was spectacularly unhealthy.

In 1957, Belafonte starred in Islands in the Sun, a film which paired him with the white Joan Fontaine. The merest suggestion of an on-screen affair incited the KKK to threaten to bomb cinemas that showed it. In fact, a scene in which the two kissed was thought too provocative and cut. In 1959, Belafonte featured in Odds Against Tomorrow and The World, the Flesh and the Devil, two more movies that centred on contemporary issues. In the former, Belafonte was cast as a bank robber uneasily coupled with a racist partner. In the latter, he played one of three survivors of a nuclear attack.

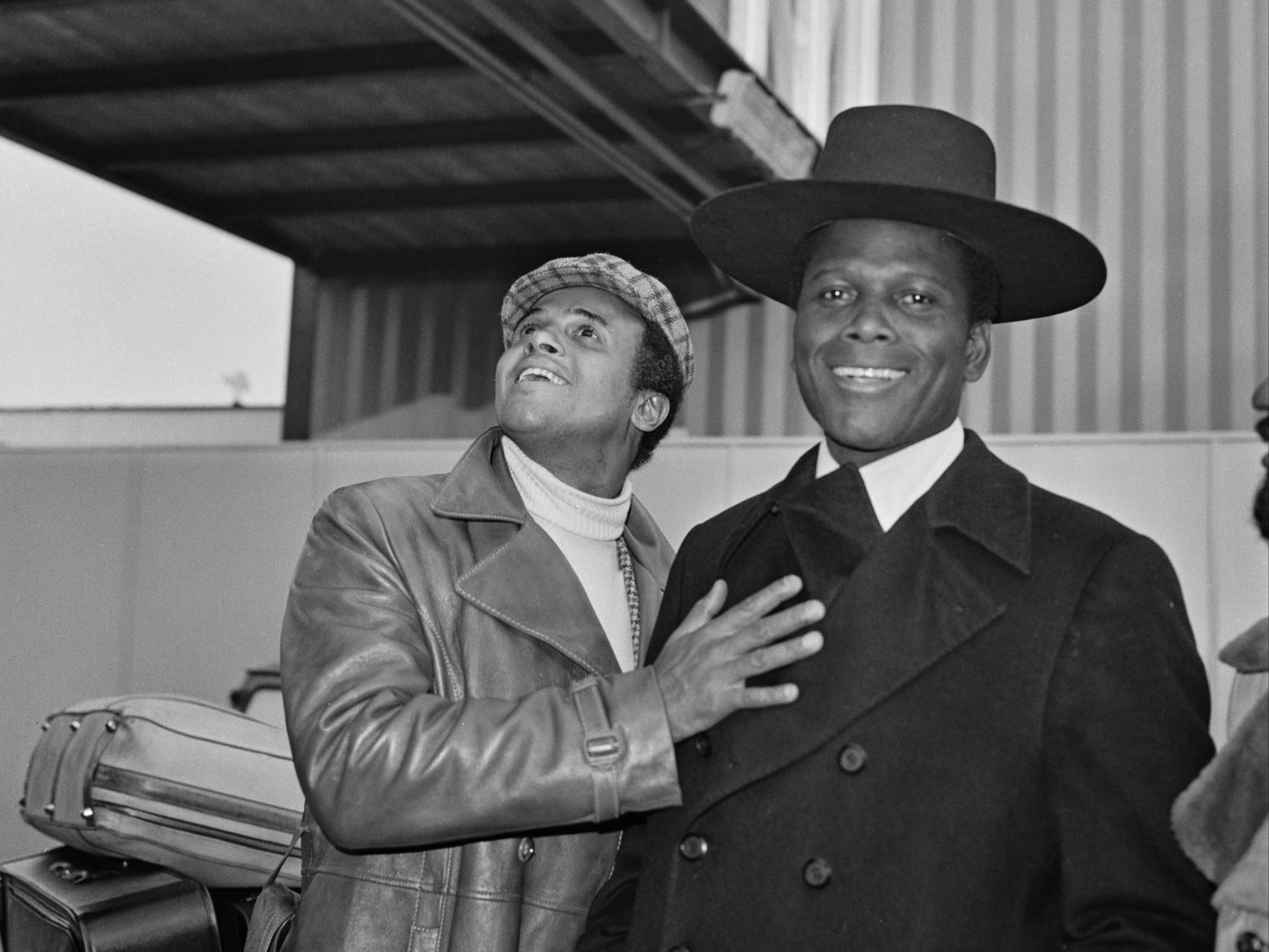

Belafonte actually rejected the role of Porgy in Otto Preminger’s Porgy and Bess, believing it promoted racial stereotypes. Indeed, although he won an Emmy in 1959 for his television show, Tonight with Belafonte, after that year he abandoned movies altogether until the early 1970s. It was during that decade Belafonte teamed up with his equally principled pal, Poitier, who directed him in 1972’s Buck and the Preacher and 1974’s Uptown Saturday Night. Belafonte’s acting career was sporadic for the rest of his life, but he contributed notable performances in 1995’s White Man’s Burden and 2006’s Bobby Kennedy biopic, Bobby.

Despite the lack of good film roles offered in the Sixties, his musical career and civil rights activities continued apace. In the first half of that decade, Belafonte recorded with Odetta and on his 1962 album, Midnight Special, an unknown Bob Dylan was invited to debut on vinyl. Despite Beatlemania denting his and the career of other 1950s singers, Belafonte continued to record million-selling albums and won a Grammy for 1965’s “An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba” which focused on apartheid issues.

Just as his social conscience increasingly drove his artistic choices, his activism intensified during the civil rights era. Belafonte supported voter registration drives in the South and helped organise 1963’s epochal March on Washington. With his hefty financial clout, Belafonte also funded the Freedom Riders and bailed Martin Luther King out of Birmingham City Jail. In fact, Belafonte had been privately providing for King and his family who were expected to survive on a preacher’s wage of $8,000.

In the early 1960s, Kennedy appointed Belafonte as cultural adviser to the Peace Corps which sent thousands of volunteers to Africa, Asia, and Latin America. At this time Kennedy’s brother, Bobby, was a lesser-known political quantity, so Martin Luther King dispatched Belafonte to locate “Bobby’s moral centre and win him to our cause”. Over the following years, the two men became close and Belafonte vigorously supported his presidential campaign in 1968. That year, Belafonte was asked to cover for Johnny Carson on his Tonight Show. Belafonte invited King and Bobby Kennedy on to the show. Within a few months, his two friends whom Belafonte had so energetically championed, were assassinated.

Over the following decades, Belafonte focused increasingly on politics and less on his artistic output, although he never completely relinquished that side of his life. In 1985, Belafonte was one of the organisers of the “We Are World” recording. Two years later, he became an ambassador to Unicef.

At the dawn of the new Millennium, as well as continuing his charitable work for African causes, Belafonte became a vocal supporter of Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez, and one of the fiercest critics of Bush’s right-wing government. He described the president as a “terrorist”, labelled both Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice as Bush’s “house slaves” and criticised the “new Gestapo of homeland security” for sabotaging American freedoms.

In fact, Belafonte’s activism, including his campaigns for HIV/AIDS awareness and other causes, arguably equalled his earlier triumphs as an actor and singer. A courageous, principled man who always put his money exactly where his mouth was, Belafonte achieved an inspirational amount for someone employed as a janitor’s assistant at the end of the Second World War. In 2006, during his Martin Luther King Day speech at Duke University, Belafonte said that if could choose his epitaph, it would be, “Harry Belafonte, patriot”.

Belafonte was married twice. First in 1948 to Marguerite Byrd with whom he fathered two children. He married his second wife, Julie Robinson in 1957. They had two children.

Harry Belafonte, singer, actor and activist, born 1 March 1927; died 25 April 2023