Four hours into the marathon recording session that yielded the 1985 hit "We Are the World," its nearly 50 participating recording artists were on the verge of taking a break. It was almost 2 a.m., and the assembled stars had many hours to go before the session wrapped.

None were expecting Al Jarreau to spontaneously burst into the universally recognizable run from Harry Belafonte's "Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)." In that moment, captured in "We Are the World: The Story Behind the Song," Jarreau's "Daaaay-O!" pierces the din and perks up the choir.

A tight shot of Bruce Springsteen's face captures his boyish surprise. Jane Fonda, who narrates the documentary, describes the serenade as a "spontaneous tribute to Harry Belafonte." Belafonte, standing in the back row, doesn't accept the salute with ease. He sheepishly smiles, eyes downcast as Smokey Robinson, Ray Charles, and others harmonize with Jarreau on the signature line: "Daylight come and we want go home."

Jarreau continues and Belafonte remains slightly abashed until his smile broadens, as if he's accepting his signature tune's supernaturally unifying power. As the cheering increases and the number of voices contributing to the chorus grows Belafonte joins them, like he's content to be part of a higher cause without being the shiniest star in the room.

By that point in his career Belafonte, who died Tuesday at the age of 96, was past the urge to stand out in a crowd of celebrities. Besides, as the reason that "We Are the World" came to be, there was no need. Inspired by Bob Geldof's formation of the U.K. supergroup Band-Aid to record "Do They Know It's Christmas?" Belafonte convened some of the biggest stars of the 1980s to record the charity single written by Lionel Richie and Michael Jackson and produced by Quincy Jones and Michael Omartian. The session began at 10:30 p.m. and didn't end until around 8 the next morning.

The payoff remains historic: the single sold more than 20 million copies and, along with sales of associated merchandise, generated $75 million for famine relief in Ethiopia and recovery and development programs in Africa through the charity United Support of Artists for Africa.

Looking back, that improvised insertion of "The Banana Boat Song" into this excerpt is fitting. Popular culture would eventually obscure the humanitarian urgency of "We Are the World" in the same way that "Day-O" came to epitomize Belafonte's reign as the King of Calypso instead of the manual labor anthem it once was.

Belafonte's entertainment career and his activism weren't often overtly entwined, but his stardom was central to marshaling celebrities to civil rights causes.

"Day-O" is the most famous track from 1956's "Calypso," one of the 30 studio albums Belafonte would release during his lifetime. It topped the Billboard charts for 31 weeks and made him the first platinum-selling recording artist in the industry's history, with the LP's sales exceeding a million copies. This career high was one of many that led to the singer, producer and actor's induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2022.

It also fed Belafonte's life's work as an activist who bridged the entertainment industry and the world of social justice. Belafonte's stage and screen career and his activism weren't often overtly entwined, but his stardom was central to marshaling other celebrities to civil rights causes. He is responsible for drawing Marlon Brando, Charlton Heston, director Joseph L. Mankiewicz and other famous performers to participate in 1963's March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Those white actors, along the James Baldwin, appeared with him as part of a CBS News roundtable discussion moderated by David Schoenbrun that aired on the same day. "It was indeed a very powerful moment to see 200,000 people, mostly Black people, but also white people, and to know that a nation such as America, and the reason that I struggle with it so hard and I grapple with it so hard is because I really believe in the potential of this country," Belafonte tells Schoenbrun in the interview. "And this country has not realized its potential and has not even begun to scratch its surface in the humanities."

In 1965 he organized a performance in support of the demonstrators who marched from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama with a roster that included Mahalia Jackson, Nina Simone, Odetta, Joan Baez, Sammy Davis Jr. and Tony Bennett.

In addition to all of this, Belafonte used his wealth and fundraising abilities to support ground efforts. Famously in 1964, Belafonte and his lifelong best friend Sidney Poitier were chased by the Ku Klux Klan as they delivered $70,000 in cash to Mississippi to support voter registration during Freedom Summer.

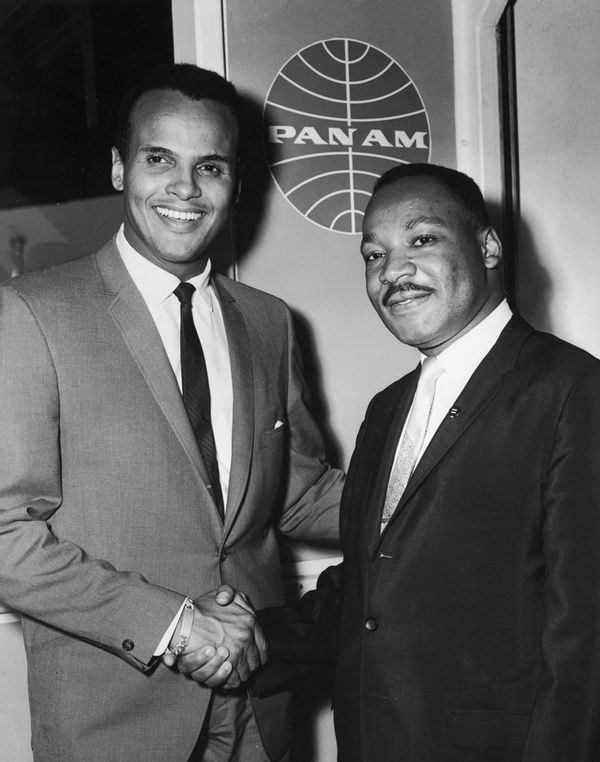

But he also put up the bail money to have Martin Luther King, Jr. released from the Birmingham jail as well as bailing out many student activists, all part of his support for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, for which he put up a share of the founding funds.

King and Belafonte were already friends by the late 1950s, according to a New Yorker profile Henry Louis Gates Jr. wrote in 1996:

King was a frequent guest of Belafonte's in New York, and Belafonte was one of the few who could serve as trusted conduits between King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, on the one hand, and the Washington establishment, on the other.

. . . [A]nd, though he's obviously proud of the role he played in the civil-rights era, he speaks of these matters with some hesitancy. King's widow, Coretta Scott King, is more forthcoming. She recalls a day in the early sixties when Belafonte told King, laughing, "Martin, one of these days some of these crackers are going to kill you, and I'm going to end up having to take care of your family." Both things came to pass, Belafonte having insured King's life heavily for his family's sake."

The success of "Calypso" marked the first major surge in Belafonte's career after years of struggling in the New York City theater scene alongside Poitier. The two men met when they were both members of Manhattan's American Negro Theater. While Poitier's stage and screen career took off from here, Belafonte was steered toward live music performance.

It was in this capacity that he found the fame he'd been pursuing, standing out as a stage performer before landing a co-starring role in Otto Preminger's 1954 classic "Carmen Jones" which paired him with Dorothy Dandridge. A post-"Calypso" role in 1957's "Island in the Sun" garnered controversy due to his character's flirtation with a white woman played by Joan Fontaine. A member of the South Carolina Legislature introduced a bill seeking to fine theaters showing the film.

"I was long an activist before I became an artist," Belafonte said.

But then, those politicians may not have seen the need to propose such measures if Belafonte didn't have such crossover appeal. Hollywood capitalized further on this in 1959 when he starred in a TV special called "Revlon Hour: Tonight with Belafonte" with an integrated roster of musicians and other performers. It won Belafonte an Emmy in 1960, making him the first Black performer to achieve this accolade. By Belafonte's report, it also earned a proposed million-dollar five-episode offer that he turned down when the sponsor, Charles Revson, required Belafonte to make the cast entirely Black.

"'Mr. Revson, let me tell you something,'" Belafonte related in the 1996 New Yorker interview, "'If you'd asked me to put on a flowery shirt and sing more calypso tunes, and dance more, because that's what white people would like, I would consider it. But what you've asked me to do — there's no way to square it. I cannot become resegregated.'"

He recalled the executive handed him a check for $800,000 and told him he was off the air.

Years later Belafonte made headlines again when, in a duet with Petula Clark during her 1968 TV special, the "Downtown" singer placed her hand on his arm, scandalizing a Chrysler Corporation executive to such an extent that the touching "incident" somehow became public before the special aired . . . to overwhelmingly positive reviews. That same year America would witness an interracial kiss on "Star Trek," see the premiere of "Julia," the first family sitcom to star a Black woman and watch Belafonte guest host NBC's "Tonight Show," where he had King on as a guest.

These are some of the many ways Belafonte put the fame for which he harbored mixed emotions to its highest use over the years, among them: working as an ambassador for multiple charitable organizations, leading a cultural boycott against South Africa's apartheid government in the 1980s, and serving as an adviser to the Women's March on Washington in 2017. (Of his role with the Women's March, he told the AP, "I'm just the plumber. I come in to fix the pipes.")

Although the mainstream success of "Day-O" and other popular singles in Belafonte's catalog remains something of a sore spot among Trinidadian calypso experts, Belafonte explained in a 2011 NPR interview that was also an anthem of activism.

"Almost all Black music is deeply rooted in metaphor," Belafonte explains. "The only way that we could speak to the pain and the anguish of our experiences was often through how we codified our stories in the songs that we sang."

Three years after "We Are the World" became a massive hit, "Day-O" saw a resurgence thanks to its prominence in Tim Burton's 1988 movie "Beetlejuice," a Generation X favorite with an all-white cast.

In that movie, Geena Davis and Alec Baldwin play a pair of ghosts who, when they were alive, were enthusiastic Harry Belafonte fans. His song features prominently in a dinner party scene where the couple pulls off their first haunting. To this day people can still mimic Catherine O'Hara's showstopping lip-synch without metabolizing the song's meaning.

"It's about men who sweat all day long, and they are underpaid, and they're begging the tallyman to come and give them an honest count — counting the bananas that I've picked, so I can be paid. And sometimes, when they couldn't get money, they'll give them a drink of rum," he said. ". . . People sing and delight and dance and love it . . . they don't really understand unless they study the song that they're singing a work song that's a song of rebellion."

Later in the same interview he adds, "A lot of people say to me, 'When as an artist did you decide to become an activist?' I say to them, 'I was long an activist before I became an artist.'" He leaves behind a legacy of being respected and beloved for both.