What is it? A claymation-y narrative adventure set on a stranded spaceship.

Release date April 16, 2024

Developer Slow Bros

Publisher Slow Bros

Reviewed on RTX 4080, Ryzen 3700x, 16GB RAM

Steam Deck Verified

Link Official site

Harold Halibut's most enduring running gag is about Sonsuz Ask, a Turkish soap opera that seems to be the only TV series the game's space-based denizens thought to take with them into the stars. Problem is, Sonsuz Ask is a real bumpy ride. Its most ardent fans will try to sell you on it—just wait for it to really pick up in season 22—but the hard truth is that you'll have to endure a lot of long, barren stretches before you get to the good stuff. Even in space, you probably have better things to do with your time.

Harold Halibut has a lot in common with Sonsuz Ask. There are parts of it that are truly worth loving: Clever dialogue, bold set pieces, gags that actually make you laugh out loud, but they're brief moments of excitement before the game returns to a ponderous baseline. And while that baseline lasts for about 13 hours rather than 20+ seasons, I still don't think I can fully recommend it.

Engineer ingénue

You are Harold, the unsophisticated, sincere, and (literally) wide-eyed handyman aboard the good ship Fedora I, which has been stuck at the bottom of an alien ocean for 50 years after a solar flare knocked it out of the void. Harold is a dreamer and an optimist—the kid at the back of class staring out of the window, always willing to help the rest of the ship's citizens with problems both technical and emotional, an open and honest soul who people naturally confide in.

Which they do regularly. The game is a strictly narrative affair: Most of your playtime is spent walking between conversations, and most of those conversations consist of one character or another unloading their burdens onto poor Harold's shoulders. The owner of the ship's general store needs someone to talk to about his marriage, the ship's captain feels unprepared for his role, someone simply must repair the relationship between a quartet of middle-aged receptionists who I can only describe as possessing a 'bus conductor genotype.'

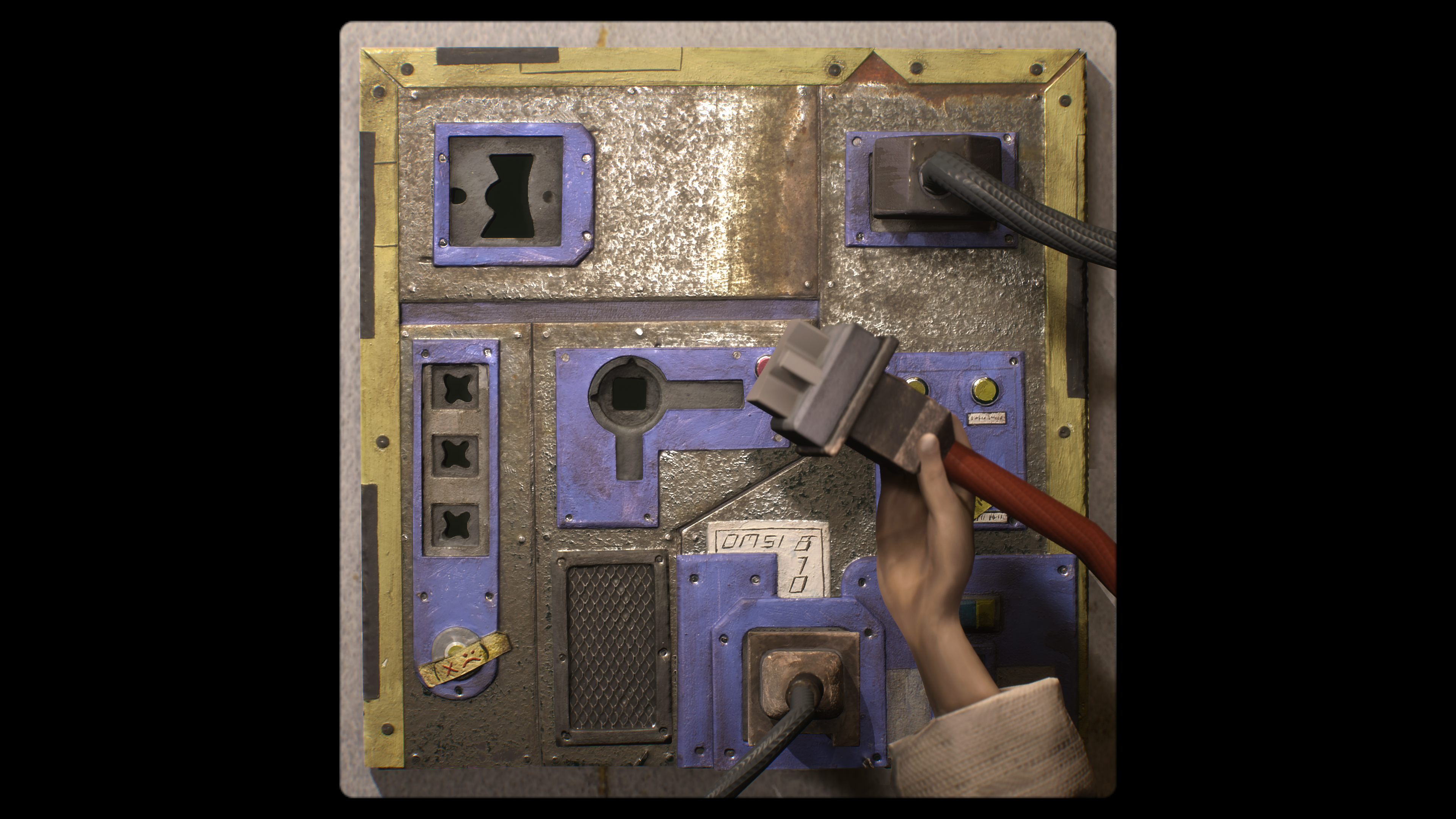

On and on it goes as you, the player, guide Harold between chats in which the Fedora I's many quirky inhabitants choose to make their neuroses the plumber's problem. It's not without charm: Slow Bros clearly has a great deal of affection for its characters. Combine that with the game's unique style of presentation—the game has an impressive handmade claymation-esque artstyle that dovetails nicely with its deliberately school-play-like delivery—and you have a recipe to pique my curiosity if not my outright investment.

But those chats often have the feeling of an afterschool special: Sweet, simple themes and morals, delivered clearly. It gets fatiguing, and all the stranger because you catch occasional flashes of a more daring game hidden underneath.

Every so often, I'd find myself gradually shutting down as this or that conversation dragged on, only to be jolted back into alertness by someone dropping a phrase like "Anarcho-syndicalist hacktivist collective," suddenly musing about the aesthetics of Christ, or (my favourite part of the entire game) a Turkish rendition of Bella Ciao kicking in as Harold gets capital-P Political. But that bolder game is only glimpsed; it's never on screen for long.

... that bolder game is only glimpsed; it's never on screen for long.

Some of those chats are optional, which leaves open the possibility of a determined player simply mainlining the game's central plot and ignoring its more sentimental side-roads, but the issue there is that Harold Halibut's story seems almost determined not to start. The pacing is just off, and would be that way even if you didn't take an hour to go do the optional task where you read a bunch of people's private letters with the postman.

Harold Halibut consists of six chapters, and I spent the first two—several hours of real-life time—waiting for something to happen. Plenty of things could have happened. The game lays down track for all sorts of interesting plots, from the sinister corporation that runs the ship to the underground cell of rebels that operates like an aquatic Silhouette from Deus Ex, but the game too often shies away from making any of its characters seem too villainous or putting any of them in too much danger.

For instance: Without spoiling too much, there's a point at which the sinister corporate CEO uncovers a big secret Harold and co have been keeping, a potentially pivotal plot moment that seems like a real threat. And then it all just kind of works out for the best, because even Harold Halibut's grasping capitalists seem to fundamentally have their hearts in the right place.

It's frustrating and fatiguing in equal measure, and a shame, because there are things to like here. The hand-crafted artstyle is an untrammelled success, and the game's '70s British kids TV show aesthetic almost manages to justify how sweet and safe the entire thing feels. Almost.

By the end of my time with it, I found myself wishing for the Harold Halibut that occasionally poked its head out: The one that broke into West German jazz apropos of absolutely nothing, that made genuinely funny jokes about politics and philosophy, and that was in general much more willing to linger in those strange asides. Instead, it spends most of its time lingering in conversations that eventually wore out their welcome and in a plot determined to play it safe.