In early 1999, the Oscar-winning screenwriter Ted Tally made a trip to Miami, where he visited the author Thomas Harris. They were celebrating: Harris had finally completed his third Hannibal Lecter novel, titled simply Hannibal, after more than a decade of writing. But the Miami get-together, Tally remembers, felt “awkward”. It was long assumed that Tally and the filmmaker Jonathan Demme would adapt Hannibal for the screen, having previously adapted The Silence of the Lambs in 1991 – it grossed nearly $300m worldwide and won five Oscars. But there was a problem. Neither man liked Harris’s new book – all 500 operatic, grisly and occasionally bonkers pages of it – and didn’t want to make it into a movie.

“We were having this celebratory dinner and we all knew we would have to break his heart the next day,” Tally tells me. “He was shocked. He had worked so hard to complete it. He was blocked for a long time to find an ending that he could make it work for him. But it didn’t work for us.”

Indeed, the conclusion of the novel sees The Silence of the Lambs’ heroine, FBI agent Clarice Starling, scoff human brains with Lecter before they run off together. As Demme said to Tally, “It gives you an icky feeling”. Jodie Foster couldn’t stomach it either and declined to return as Starling alongside Anthony Hopkins’s Lecter.

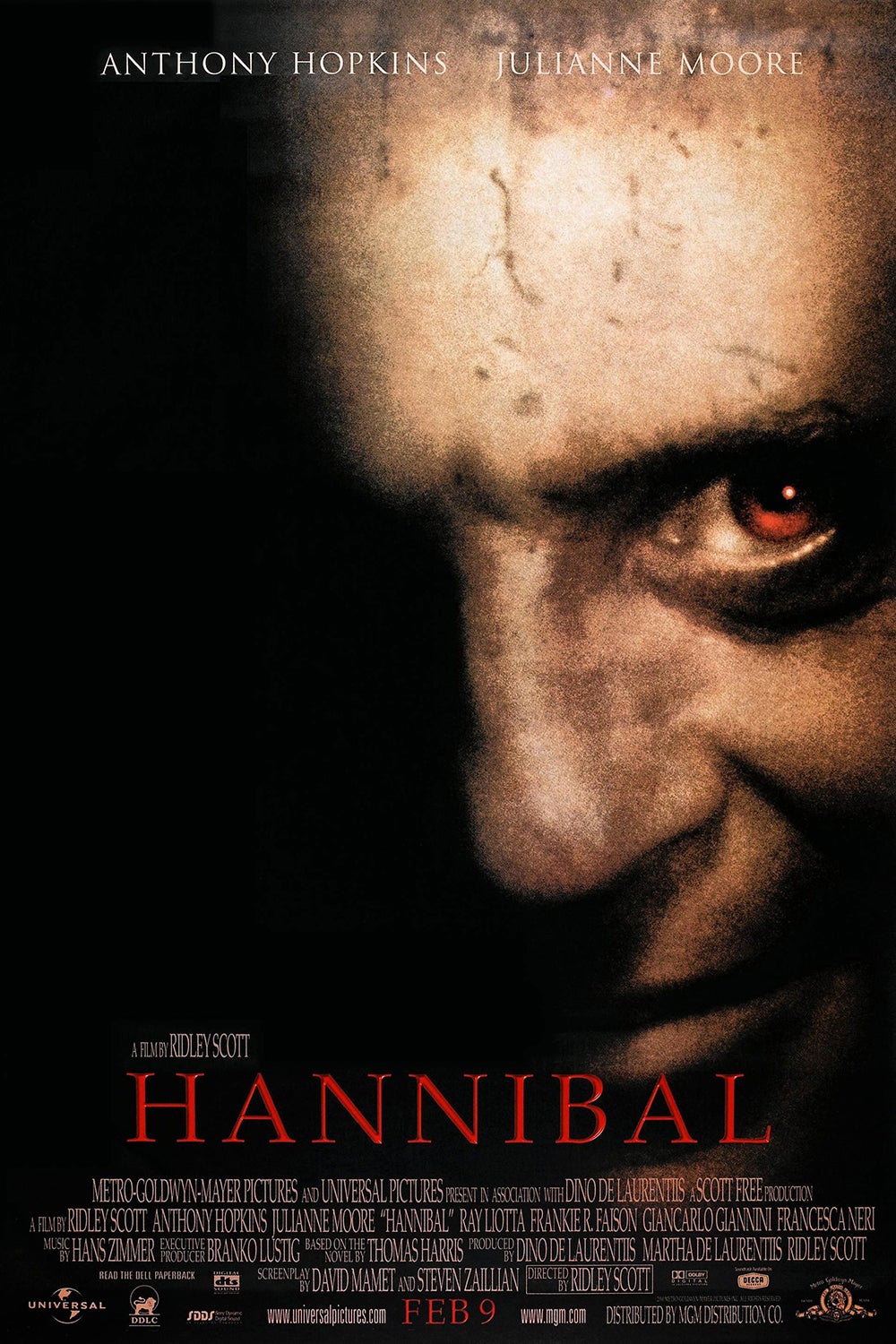

Hannibal was ultimately directed by Ridley Scott, with Julianne Moore replacing Foster as Starling, and opened in cinemas 25 years ago today. Scott certainly had no qualms about the novel’s violence. “I found it quite humorous,” he once said. But the film is less a satisfying sequel than an under-seasoned side dish. It’s perfectly quaffable, of course – Scott is in his element with scenes of the escaped Lecter swanning around Florence as a culture-vulture/cannibal fugitive, doling out gruesome slayings that border on punch-the-air vigilantism. But Hannibal was a case of Dr Lecter eating himself. A victim of his own popularity, he steps forward as the leading man and plays the anti-hero, out-monstered by a lobotomised misogynist and a deformed paedophile with a sounder of man-eating pigs.

Before Hannibal, the prospect of a sequel to The Silence of the Lambs was tasty stuff. It was the focus of long-running speculation and rumours, and the question of whether Hopkins and Foster would return became one of the great “will they, won’t they” sagas of the Nineties (like Ross and Rachel, but heavier on cutting people’s faces off).

We just felt that he had betrayed his own characters. Clarice had gone over to the dark side and flipped her personality

Dr Lecter made his movie debut in Michael Mann’s Manhunter (1986), a then-overlooked adaptation of Harris’s first Lecter novel, the superb Red Dragon. In Manhunter, Hannibal is very much a supporting character, played with chilly, clinical precision by Brian Cox, better known as Succession’s Logan Roy. The film was not a success and producer Dino De Laurentiis passed on Harris’s next book, The Silence of the Lambs, licensing the Lecter rights to Orion Pictures.

With Anthony Hopkins taking on the role for Orion, Hannibal Lecter became the defining movie monster of the Nineties – the template for every learned psychopath, every serial killer hunt story, every true crime obsession since. His favourite meal – liver with fava beans and a nice chianti – became a universally-quoted touchstone; his restraining mask an instantly recognisable Halloween costume. But Lecter became something else, too: valuable IP.

Tally remembers early talk of a Lambs sequel. But neither he nor Demme would do it without Thomas Harris. “We decided pretty quickly that we didn’t want to do a sequel on our own, because we owed so much to [him],” Tally says. In other words, it would have to be a Harris story or nothing. “We all waited with increasing impatience for him to finish,” adds Tally, laughing. Hopkins believed it would be worth the wait. “You cannot rush him,” he said. Meanwhile, De Laurentiis, who had first refusal dating back to his Red Dragon/Manhunter deal, paid a reported $10m for the rights to the new novel. He had passed on Lambs, but would not make the same mistake again.

In Harris’s story, Lecter – who escaped at the end of The Silence of the Lambs – is living under an alias in Florence, evading not only the FBI but a bounty put on his head by surviving victim Mason Verger (played by Gary Oldman under grotesque prosthetics in the movie). Verger is a millionaire child molester and the most irremediably vile character in the whole Lecter-verse – no easy feat in a storyworld that includes the woman-skinning serial killer, Buffalo Bill. His backstory is nasty stuff: Lecter, formerly Verger’s psychiatrist, drugged Verger and persuaded him to slice off his own face, feed it to his dogs, and eat his own nose. Paralysed and faceless, Verger plans to capture Lecter and feed him alive to monstrous, trained-to-kill pigs.

In the novel, Verger’s abused sister kills him by shoving a pet eel into his mouth, but viewers would have to wait until the Hannibal TV series with Mads Mikkelsen – a three-season exercise in trying to go as dark as possible – to see the death-by-eel. It’s one of several elements excised from the film by screenwriters David Mamet and Steven Zaillian.

The Hannibal novel is a curious beast. It’s a book that can only be understood in the context of The Silence of the Lambs’ massive success, picking up on the popularity of Lecter and Starling while subverting expectations and trying to outdo Lambs’ darkest moments. It feels more like a sequel to the film than the source novel, yet it goes to places the movie characters would never have travelled. It’s impossible to imagine Foster’s Starling chowing down on brains. “We just felt that he had betrayed his own characters,” Tally says. “The Clarice Starling he created in The Silence of the Lambs was [so] rich. She had sort of gone over to the dark side and flipped her personality.” He adds: “Tom’s best work is sprinkled with the dark side but doesn’t give in to it.”

Foster agreed. “The original movie worked because people believed in Clarice’s heroism,” she once said. “I won’t play her with negative attributes she would never have.” Even with Hopkins on board, Foster’s departure doomed Hannibal to feel forever inauthentic. Julianne Moore is a fine actor, but she’s not the real Clarice Starling.

There’s a question of whether this is the same Lecter, too. Far more agreeable than the Lecter seen in Lambs’ maximum security prison-cum-dungeon, he no longer gets under your skin by rolling the word “Clarice”. He also seems happy enough soaking up the culture in Florence until crooked Italian cop, Pazzi (Giancarlo Giannini) attempts to shop Hannibal in and claim Verger’s reward. It’s hard to picture this Lecter attacking and eating the tongue of an innocent nurse, a story told in The Silence of the Lambs. This Lecter is a charmer. (Hopkins was lethargically modest as ever about his performance as Hannibal. “I just read the script, learn the lines, and do it,” he said at the time.)

It’s a well-chewed criticism of Hannibal: he’s no longer frightening. Playing the anti-hero, his only victims are villains themselves. The Italian cop receives a well-earned disembowelling; Mason Verger, in an act of undeniable justice, is fed to his own pigs. Verger’s long-suffering assistant tips him into the pigs’ enclosure at Lecter’s suggestion. (“Why don’t you push him in? You can always say it was me.”)

As grisly as The Silence of the Lambs is, the true horror is psychological. By contrast, Hannibal is about crowd-pleasing gore and gut-spilling triumph. Most horrific of all, of course, is the film’s final course, when Lecter opens up the cranium of Clarice’s nemesis, Justice Department official Paul Krendler (Ray Liotta), and feeds him his own brains. “That smells great,” says the sedated Krendler as his prefrontal lobe sizzles in the pan. But even Hannibal, a film in which you want to see a mutilated tetraplegic get eaten by a pig, didn’t have the appetite for Harris’s original ending. Unlike the literary counterpart, Moore’s Starling doesn’t go to the dark side and eat Krendler’s brain; nor does she run off with Lecter. “You’re going to lose some babies here, you know,” Scott recalled telling Harris. The scene, though appallingly unpleasant, is played for dark laughs as well as horror. “If you can’t keep up with the conversation, you’d better not try to join in at all,” Lecter tells the confused, slurring, brain-exposed Krendler.

Released on 9 February 2001, Hannibal was met with muddled reviews but made $351m – a second box office hit in a row for Scott following Gladiator. There’s a curious quirk about the Lecter films: because of the production history – switching between producers, studios, directors, and actors – each film feels like it belongs in its own world, making them easy to digest as standalone stories rather than a succinct series. The closest the series comes to replicating The Silence of the Lambs is prequel Red Dragon, which swiftly followed in 2002 and was once again adapted by Tally, an effort to forget Manhunter and produce a more faithful adaptation with their star player, Hopkins, back in the dungeon.

As Tally says, Lecter is at his best in restraints. “Lecter’s power comes from being compressed into a cell – his mind can run the world from that cell. But if he’s running around, he’s got too much freedom… less is more with him.”

The return of Thora Birch: ‘I wouldn’t trade child stardom… but it has a heavy price’

The last thing we need is more biopics – but Meryl as Joni sounds irresistible

This year’s Oscar nominees are furiously political – so why are their stars silent?

Catherine O’Hara made deeply flawed characters not just bearable but beloved

Laura Dern: ‘David Lynch saw things in me that I didn’t see in myself’

I watched ‘Melania’ on opening day. Why I did is one of many questions I’m left with