Rather than a review, this is a ‘hands-on’ of the ZimaCube since we know that our machine was an earlier version that has since been superseded. Some of the issues talked about here have been resolved, although some remain.

But the overall chassis design, processor, and memory configurations remain the same in the latest incarnation of the ZimaCube, so this coverage might give you some idea if you wish to purchase one.

ZimaCube: Price and availability

- How much does it cost? From $699

- When is it out? Soon, Pre-order available

- Where can you get it? On Pre-order from Zima

The ZimaCube is one of those curious products offered on Kickstarter to garner reaction, feedback, and sales ahead of its retail release by IceWhale Technology Limited.

The Kickstarter has now ended, but the process provided some useful information about the gestation of the ZimaCube and how the current product is different from the one that first appeared.

At the time of writing, the product is on pre-order, with the ZimaCube entering production in early March.

The asking price for the ZimaCube is $699 for a model with 8GB pre-installed and $729 for one with 16GB. In all other respects, these two options are identical.

For an N100-powered PC, this is very expensive.

ZimaCube: Specs

ZimaCube: Design

- Heavy metal enclosure

- Mini ITX mainboard

- Poor backplane connection choice

At a backbreaking 5.4kg, this is one of the heaviest NAS machines we’ve ever encountered. It is so heavy that we assumed the drive bays were populated when it came out of the box.

IceWhale Technology built a substantial, roughly cube-shaped steel chassis with the drive bays in the bottom and the MicroATX main board mounted horizontally about 9cm from the top.

Seven bays are under a flimsy plastic louvre grill. Six are designed for SATA mechanisms, and the seventh is for additional M.2 drives using a U.2 slot and carrier card.

In our hardware, the U.2 carrier card was missing, which left only the two M.2 slots on the mainboard for that purpose, and one of those was occupied with a 256GB drive for the OS.

The six drive trays are a combination of metal and plastic, but they’re not a tool-free design and require screws to hold the drive to the cradle before insertion.

For whatever reason, in our system, slot one reported the drive was bad, irrespective of the drive we inserted, but all the rest were good.

The mainboard is accessible with the removal of four screws, and the top of the ZimaCube detaches. The space inside seems excessive, but the enclosure is common with the ZimaCube Pro, which needs more cooling for its Core i5 processor than the N100 in this system.

One good design decision is to separate the drive cage and system areas for cooling purposes. In the lower section with the hard drives, the air is pulled through the cages using two 80mm rear-mounted fans that then eject that heated air. Therefore, hard-working drives shouldn't impact cooling for the system area, and vice versa.

Our mainboard was labelled as a 1.1 version, but from the Kickstarter blog, we know that 2.0 has appeared and 3.0 is soon to be released. On release 2.0, the two extra SATA ports that appear on our board have disappeared, and there are numerous changes to the way PCIe lanes are distributed. But more on that later.

A feature we genuinely hated was how the motherboard was connected to the backplane using an EDP connector or Embedded Display Port. This cable is often used to connect the display in a laptop, and we’ve never seen it used in this fashion. It is a tiny and easily damaged line that extends the PCIe bus to the backplane electronics.

Other than the fragility of this attachment, what’s most annoying is that this machine doesn’t use a standard PCIe header to connect. Therefore, if the mainboard dies or you want something better, it’s impossible to connect the backplane to another Micro ATX board.

That was a significant mistake, but other issues question the thinking behind the ZimaCube and how it ended up with an N100 processor.

Features

- N100 CPU

- 16GB of DDR4

- Only 9 PCIe Lanes

For those who have read many of our Mini PC reviews, the subject of PCIe lanes is often a topic of discussion. Not all processors get the same number of lanes, and they are critical in dividing the available bandwidth between the ports the system has.

Most systems tend to oversubscribe ports to bandwidth, thinking that not all users will have something plugged into every port, and if a bottleneck occurs, the system can throttle the bandwidth as needed.

For those who have looked at the ZimaCube and compared it to the ZimaCube Pro, a few things immediately become apparent, not least that the Pro machine has Thunderbolt and four 2.5GbE LAN ports, not two. That’s because the Pro uses the Intel Core i5-1235U, a CPU that is PCIe 4.0, and has a PCIe 3.0 chipset support with, critically, 20 PCIe lanes.

Meanwhile, the N100 used in the ZimaCube has no CPU PCIe lanes; only nine are provided by the PCIe 3.0 chipset.

Nine lanes aren’t enough when you have six SATA drives, four M.2 slots, dual 2.5GbE and multiple USB ports.

While the ZimaCube specs quote a single PCI x4 Gen 3 slot, the board in our machine had physical x16 and x8 slots. We concluded that it had only a single PCI lane for each slot, and since this is downstream from a PCIe switch that connects using a single lane to the system. As a result, the slots share a single PCIe 2.0 lane, and that’s insufficient to use them for a 10GbE adapter since they only have half the bandwidth needed for that device. The other slot and the motherboard-based SATA ports are all linked off the same PCIe switch.

To say that isn’t ideal is a massive understatement. From what information gleaned from the 3.0 board announcements, it appears that a better PCIe switch has been used on that design, and the lanes have been reorganised to provide at least one PCIe 3.0 lane to each slot.

But that’s far from the single Gen 3 x4 slot quoted on the Zima website, and frankly, given the limited lanes, that was never achievable.

It’s also worth noting that the maximum amount of memory the N100 can address is 16GB on a single memory lane. That amount is insufficient for those wanting to use virtualisation or docker modules. It is DDR4 memory used in the ZimaCube, not DDR5, which can be used with this processor.

Leaving the pre-production nature of the ZimaCube sent to us aside, in whatever way it is sliced and diced, the N100 was a poor choice of processor for this project. It doesn’t have the PCIe lanes needed for a six-bay NAS with dual 2.5GbE NICs, and however creative the IceWhale Technology engineers get, those limitations make this a less desirable NAS.

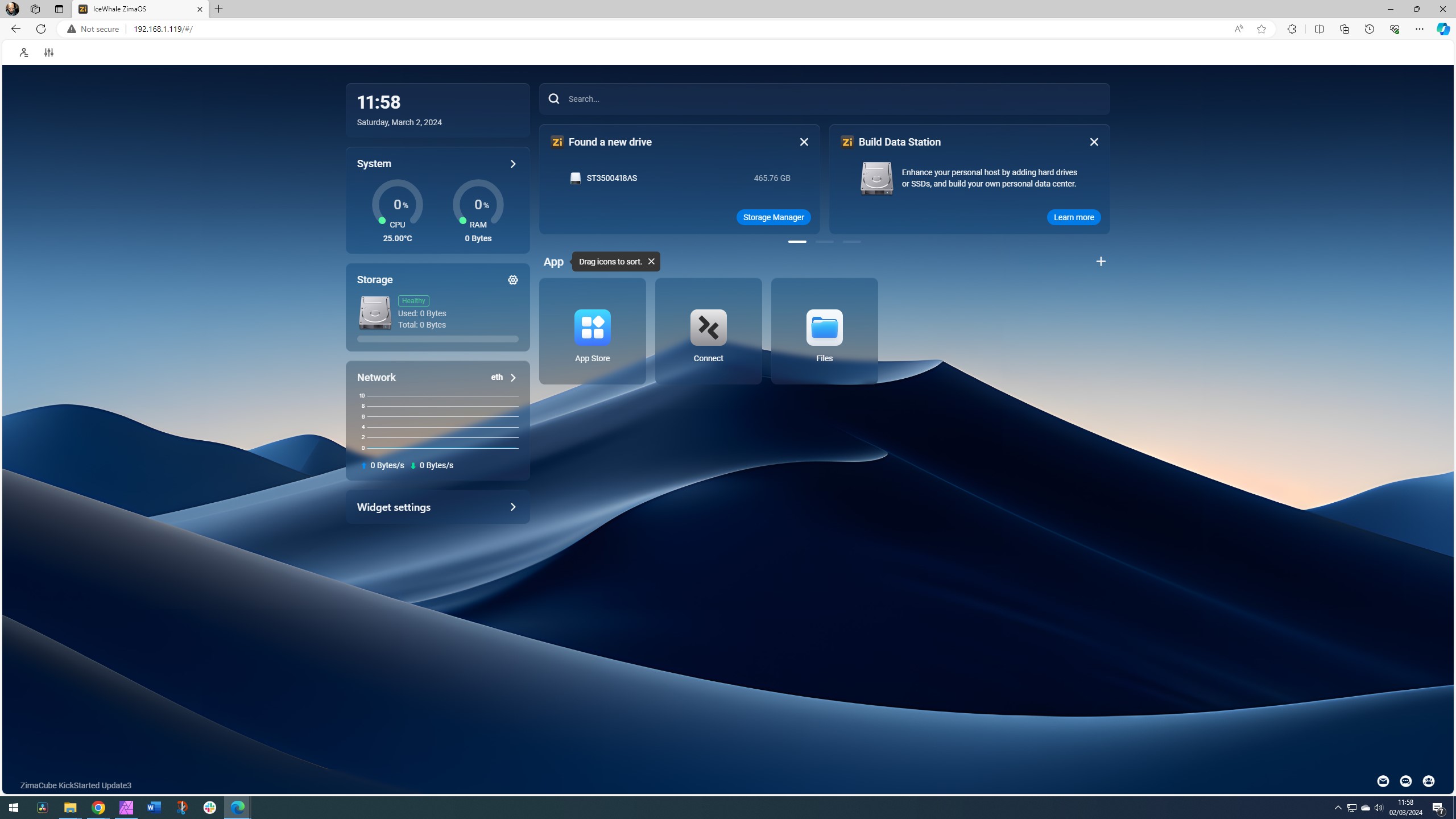

ZimaCube: ZimaOS

By default, the ZimaCube is supplied with ZimaOS, a Linux NAS operating system created by IceWhale. IceWhale states that this hardware can run TrueNAS or Unraid if required.

Anyone familiar with CasaOS will immediately be familiar with ZimaOS, a spur from that original code.

From the GitHub documentation for ZimaOS, it appears that the AppStore, Storage management, widgets and file sharing all came from CasaOS, with IceWhale Technology creating bespoke remote access and auto backup.

What was initially missing was RAID functionality, but this has since been added as ZimaOS moved from an Alpha to a Beta stage.

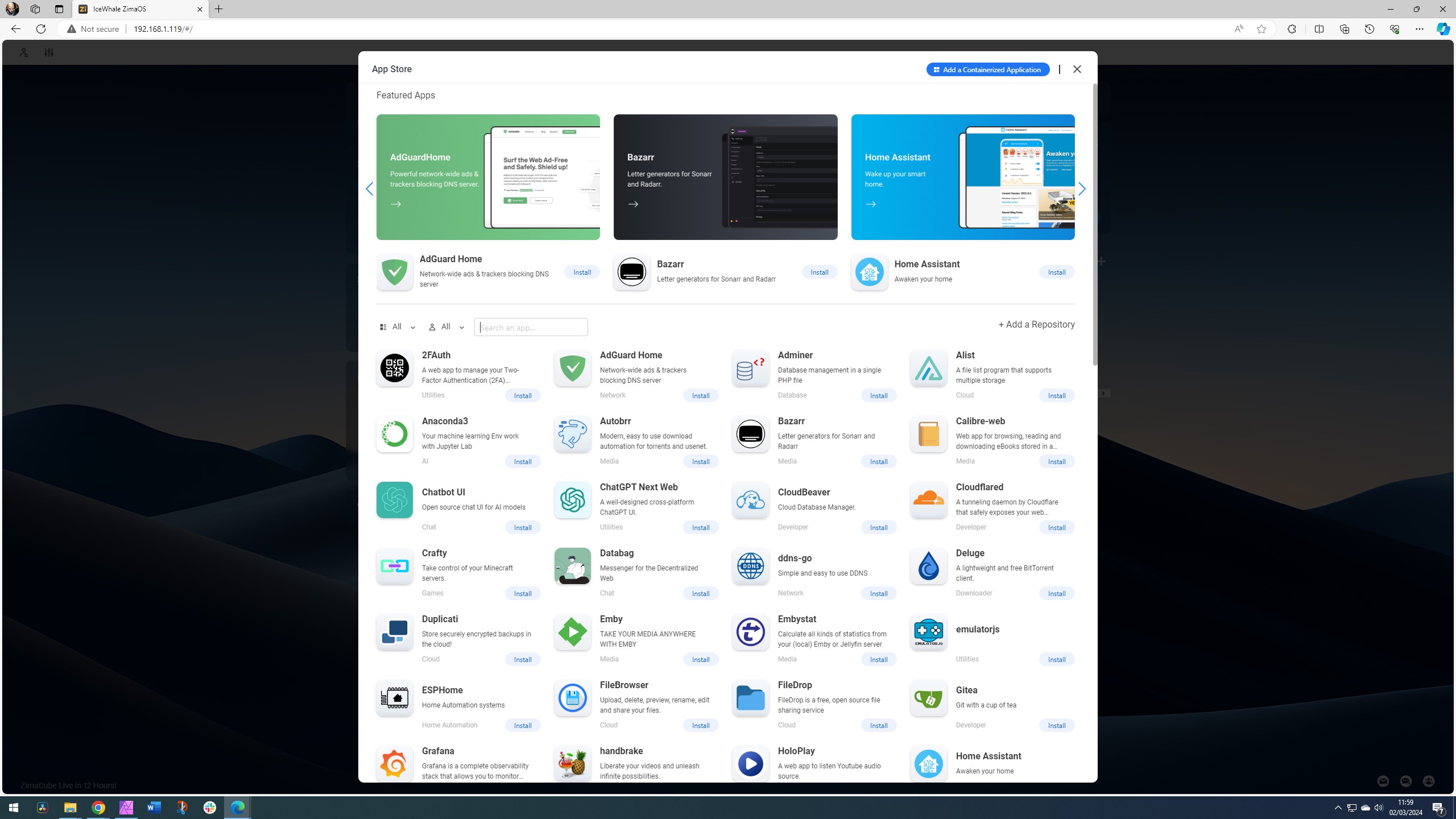

The web-based interface and application selection are directly sourced from CasaOS, and it makes for a much more friendly environment for those for whom TrueNAS and Unraid might prove overwhelming.

That said, the simplicity of ZimaOS is also a weakness since it doesn’t have all the controls that some might expect. While it is now at version 1.0, ZimaOS is still very much a work-in-progress.

As an example, the storage system does enable some basic RAID layouts, but it won’t do any of the clever hybrid RAID tricks that many NAS OS enable. In our testing, we put four 500GB drives and a single 1TB drive into five bays. But we still only ended up with roughly 2TB of space under a RAID 5 arrangement.

There are no file system choices, and we assume that it is using BTRFS, but with TrueNAS, many are convinced that ZFS is the way to go.

The whole solution is currently in a slightly odd place. Things that normally come much later are already in place, like the AppStore. Other functionalities that are generally taken for granted are either unfinished or missing.

That said, the app selection is reasonable, and we clicked to install Plex with the minimum of inputs and messing around (unlike TrueNAS Scale) and got the service working very quickly.

There are client tools for various platforms, and when complete, these should be able to easily connect local and ZimaCube services in an elegant fashion. But they aren’t finished, and some of the functionality needs to be worked on.

Overall, ZimaOS shows some promise, but it needs some work to deliver the core functionality that serious NAS users expect.

However, IceWhale Technology has gone further with its initial NAS platform than many companies, possibly because of the boost it received from using CasaOS's foundations.

ZimaCube: Early verdict

This really isn’t a true verdict since this isn’t the commercial release of this hardware or software. It’s more of an appreciation of what the future might hold for the ZimaCube and its operating system.

Having been a little late to this party, it's interesting to read all the changes that the Kickstarter project initiated, especially with respect to the PCIe lanes on the N100. While the commercial 3.0 motherboard looks to address some of these issues, the reality is that the N100 wasn’t a good choice for a NAS with this many drives and ports.

Moving up to an N300 won’t help things, as Intel also blighted that with just 9 PCIe lanes.

In retrospect, the ZimaCube should have been a four-bay NAS, maybe with two M.2 slots, a dual 2.5GbE NIC and a couple of USB 3.2 Gen 1 ports. Oddly, this is the spec that another Kickstarter, Ugreen’s DXP4800 NAS, chose.

To support the bays and options installed in the ZimaCube, the platform needed upgrading to that of the ZimaCube Pro, which uses the Intel Core i5-1235U.

That Pro machine starts at $1,199, much more than the basic ZimaCube. Also, it needs to be pointed out that it is possible to buy an N100-powered Mini PC with 8GB of RAM and 256GB of storage for around $150. Admittedly, that won’t come with six SATA bays and an enclosure built like a tank, but in terms of the performance potential, it has the same.

In short, IceWhale Technology needed to stick with the ZimaCube Pro concept and accept that the ZimaCube was heading down the wrong track. But once this train started to run on Kickstarter, we can appreciate that changing track so decisively wasn’t something those behind it were keen to do.